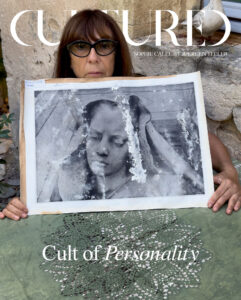

NOMINATED BY BRIGITTE LACOMBE

29–New York

Hero Bean Stevenson has shot for clients including Maison d’Etto and Carven, written and directed short films, and co-founded an art and design gallery, Raum, in Los Angeles. All the while, she has cultivated a distinctive, spare approach to black-and-white photography.

“When I photograph a subject, it is first and foremost about creating a moment of recognition—engaging with as open and direct of an energetic channel as possible, and experiencing freely the moment of connection. This act of seeing, of looking at one another with vulnerability and acceptance, is what makes the present profound, and what makes the future seem bright and possible.

I remember putting together these little shoots with my friends who were also barely teenagers at the time. I’d make reference boards, which I still have, that were very heavy on scanned Lindbergh, Ritts, and Knight images, torn out Vogue and Lula pages, pictures of Edie Sedgwick, pictures of David Bowie, pictures of Margot Tenenbaum… they’re such Virgin Suicides-esque hodgpodges.

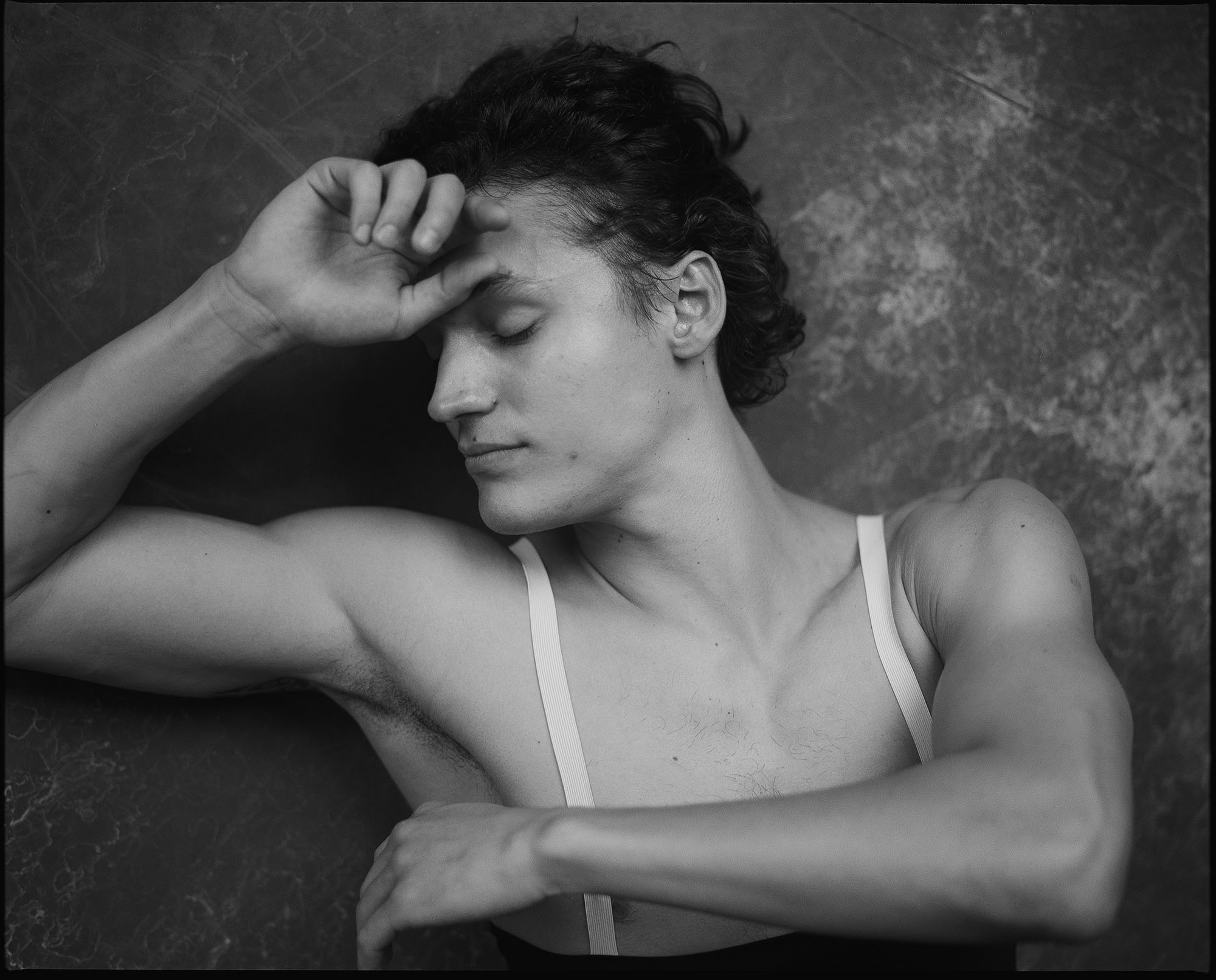

When I began to turn my referential attention and personal practice toward portraiture, I fell in love with Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe. There was an energy that the men in their images embodied—a seismic convergence between strength and vulnerability—that was just so profound and empowering to me. And when taking pictures of men, I have found myself experiencing a heightened and personal form of the same energy, which has felt beautiful.

When I take a picture of someone, it’s very intentional, specific, and inspired by the energy I feel when I look at them. Sometimes it happens with the people that I know intimately, but often it happens with people I don’t know personally at all… people I have felt infatuated by, or inspired by in some way … but that in itself is another kind of closeness that can be just as substantial, even if only for a moment.

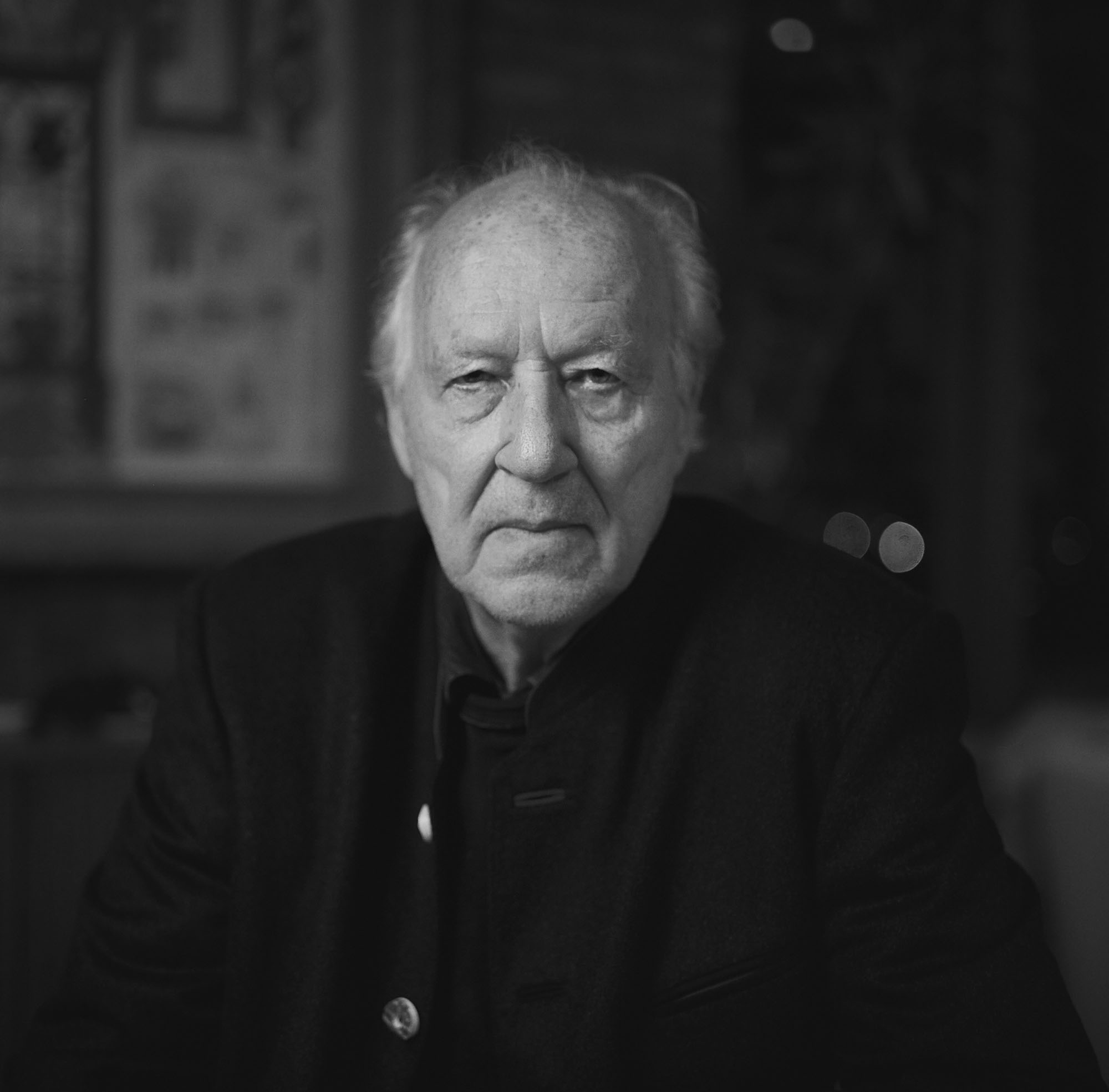

I took Werner Herzog’s portrait in 2023, and it was an unexpected moment that felt completely spirit-fortifying. I had been invited [to a film set] to shoot stills, and knew that while it had been a lifelong dream of mine to create a portrait of Werner, it was very unlikely that I’d get to. At the end of the day, I had one exposure left in the roll, and the light had all but gone in the loft.

The thought of approaching him for a formal portrait was intimidating, but it felt like a necessity. The quiet strength, openness, and mountainous presence that I was met with when I looked through my camera, and then up at him as I clicked the shutter, was invigorating in a way that I cannot describe. I am grateful that the portrait can.”

in your life?

in your life?