As a new art season opens, let’s be clear about where we are. On Aug. 4, following Executive Order 14253, “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” the National Park Service announced that it would restore and reinstall the monument to a disgraced Confederate General, Albert Pike, an avowed racist, who resigned after being accused of misappropriating funds and overseeing a wartime atrocity. (A Ku Klux Klan chapter in Illinois was named after him in the early 20th century.)

On August 12, a letter from the White House sent to Lonnie G. Bunch III, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, announced, per the same Executive Order, that they would be reviewing Smithsonian programming. “This initiative aims to ensure alignment with the President’s directive to celebrate American exceptionalism, remove divisive or partisan narratives, and restore confidence in our shared cultural institutions,” it reads. By trying to work with the White House just enough, so it seems, to protect the nation’s museums, Secretary Bunch performs a delicate balancing act. On September 3, he wrote to his staff, indicating that the Smithsonian would conduct their own internal review that was “nonpartisan and factual” while asserting the Smithsonian’s independent “authority over our programming and content,” in a challenge to presidential overreach and in recognition of the separation of powers. (The Smithsonian was established by Congress and is overseen by a Board of Regents including the Chief Justice, the Vice President, six members of Congress and nine citizens.)

It’s certainly not a boring time to be an art critic in the United States, while governmental edicts dictate that slavery’s defenders get their statues raised, buffed, and shined, and that slavery’s material and historical consequences should either be deemphasized or stricken from the record in our national museums. Culture itself is in crisis, not criticism, despite what you may have read. As the Critics’ Table contributor Domenick Ammirati reminds us, in his Spigot newsletter, crisis is a fundamental feature of modernity. His essay, “Can We Please Stop Talking About the Crisis in Criticism?” (yes, please!) traces back the perpetual-seeming topic to Maurice Berger’s 1998 anthology The Crisis of Criticism and beyond.

As I look to the season ahead and look back on the first year of the Critics’ Table, I’m proud of the writing we’ve published, yet desiring more than ever to see more art of real consequence—and risk. The questions on my mind at the start of the season are: Does art have any real power? And, if so, who does it serve, and to what end?

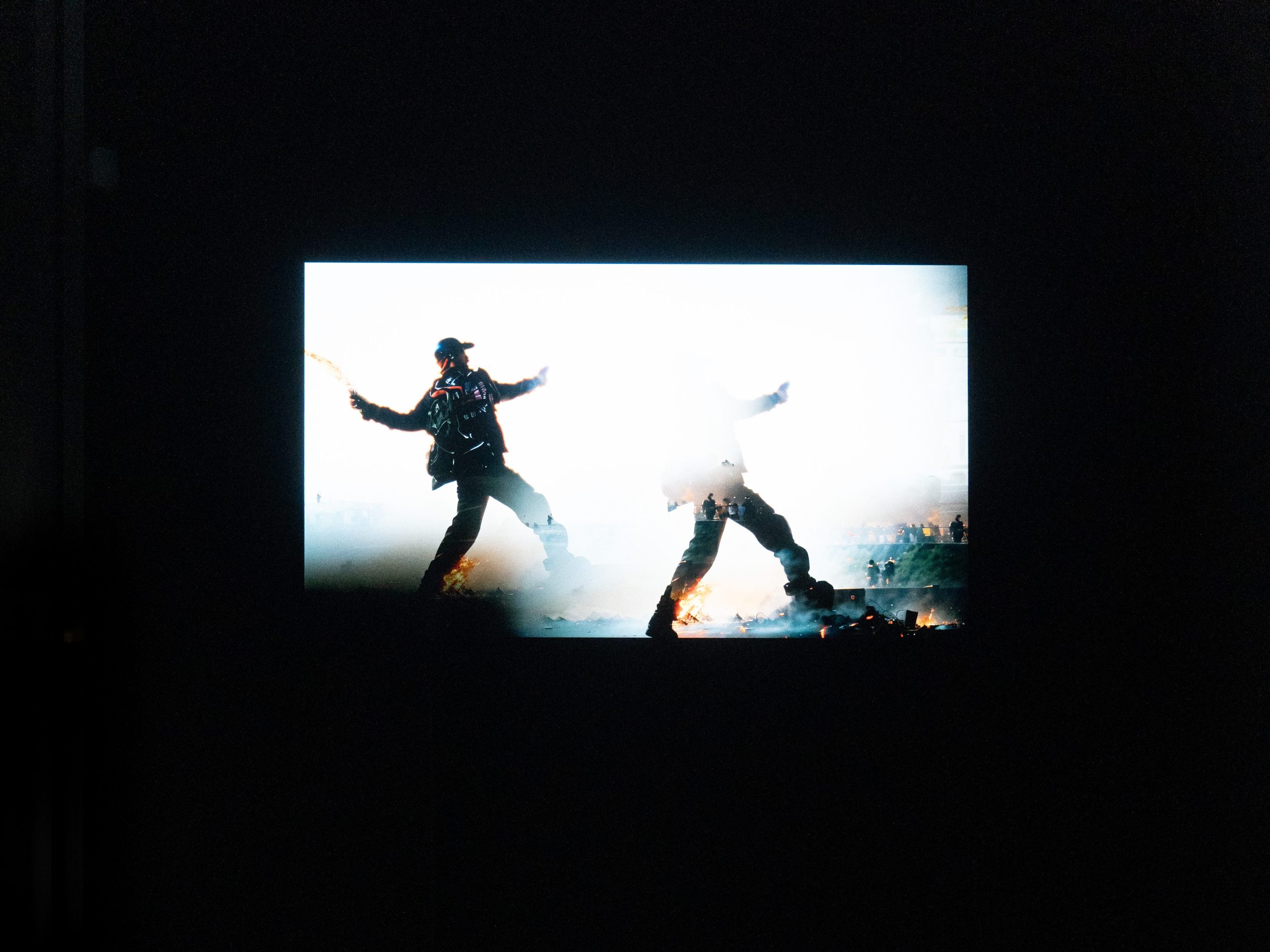

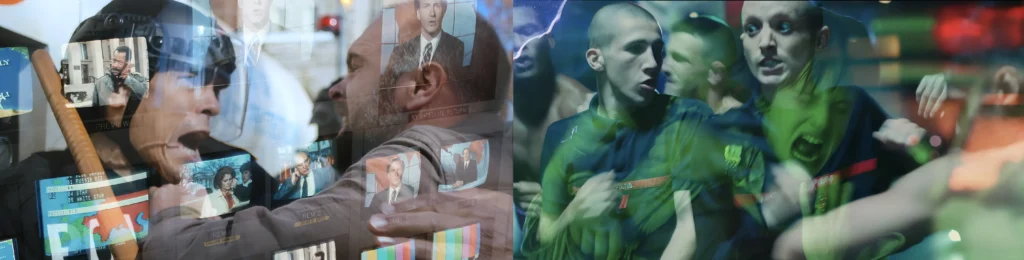

Add to this that, as critics, we have to reach an audience subject to an Internet environment increasingly inundated with A.I. slop. And A.I. slop has found its way into the galleries too. Kenny Schachter’s show, “Art in the Age of Robotic Reproduction,” of robo-paintings and sculptures, framed by a jumbled mashup of A.I. with a Cliff’s Notes understanding of Walter Benjamin, remains the worst show I’ve seen this year. But—more importantly—Marco Brambilla’s “Limit of Control” at bitforms gallery, which ran from late fall 2024 to this January, is my pick for the year’s most under-appreciated gallery exhibition: It was as prescient about the theater of political violence and protest as it was a deep exploration of A.I.’s potential as an editing and compositional tool, all while dramatizing the spectacular results when systems are pushed too far. I’ve never seen a better application—and examination—of A.I. in art before or since. I reviewed it positively, and my appreciation of the show has only continued to grow ever since.

In the wake of recent political events, I reread my colleague Johanna Fateman’s brilliant essay, “How Cameron Rowland Became the Leading Land Artist of the 21st Century” (my favorite piece of critical writing we’ve published to date) on the artist’s exhibition, soon closing, at Dia Beacon. (“Properties” is on view through Oct. 4.) Rowland’s work and Fateman’s review are acutely relevant to our current moment: Both are antidotes to the monumental mess in Washington. Rowland excavates history to suggest how the reverberations of slavery, and the profits extracted from it, continue to shape public life and economic conditions (from racialized wealth disparity to exploitative successor institutions, like sharecropping and the U.S. prison system), and Fateman provocatively places this work in an American art-historical genealogy of Land art and minimalism.

Rowland’s art might possess the power to make a critic like Roger Kimball (editor and publisher of conservative journal The New Criterion) foam at the mouth. Looking back on last year, too much attention was paid to Dean Kissick’s December 2024 Harper’s Magazine cover story, “The Painted Protest: How politics destroyed contemporary art” and not enough to the rightwing cultural long game. Kissick’s use of his mother’s maiming in an accident, while she was on her way to see an exhibition at the Barbican in London, sensationally opens an otherwise baggy nostalgia trip that idealizes the art world of the author’s youth. (We published the best examination of that essay’s flaws and inherent contradictions, in Ajay Kurian’s masterful response “Make Art Great Again.”) Kissick dressed up—for a play at virality—an argument that Roger Kimball has been pushing for years. Kissick’s title even closely echoes that of Kimball’s 1990 book Tenured Radicals: How Politics Has Corrupted Our Higher Education.

But it’s Kimball’s much more recent essay, “Restoring American Culture,” first given as a lecture at Hillsdale College on Jan. 29 of this year, that is more ominous now. In Roger Kimball do we find a neofascist art critic? He sees, in the leadership of Donald Trump, the promise to not only “spark a political restoration, but also a new cultural golden age.” Here is a self-professed art critic, successor to Hilton Kramer as editor at The New Criterion (a position held after Kramer was chief critic at The New York Times), finding in Trump’s “boundless energy” a beacon of “common sense.” Lacking from Kimball’s recent writing is any substantial constructive vision for what new art should be.

He’s a disciple of Kramer, who has lost his teacher’s power to see, assess, and describe. Kimball’s language is flattened by party dogma of the sort you might expect from a man in a bowtie spitting the word woke. While he may seem ridiculous, we ignore him at our peril. Kimball, I fear, is the loyalist type who would be tapped to replace Secretary Bunch at the Smithsonian if he fails to hang on. Though I doubt Donald Trump has ever heard of Kimball, I could see him as the selection of Russell Vought, Project 2025 co-author and architect, and signatory to that August 12 letter to Secretary Bunch. While I think Kimball would bristle and reject the association with fascism, how else to describe his sycophantic praise of the President paired with a nationalist art-historical vision?

The more relevant Harper’s piece to revisit as we look to the art season ahead is the July 7, 2020, “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate,” an anti-cancel culture PSA that warned that, “censoriousness is … spreading more widely in our culture: an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty.” Written in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, the signatories called to “uphold the value of robust and even caustic counter-speech from all quarters,” even in the face of “swift and severe retribution in response to perceived transgressions of speech and thought.” The motley group—including Bari Weiss and David Brooks alongside Noam Chomsky and Cornel West—cannily warned of “institutional leaders, in a spirit of panicked damage control… delivering hasty and disproportionate punishments instead of considered reforms.” Where are these concerned defenders of free speech now? One tally found that fewer than a quarter of these same signatories registered a public protest after the abduction of Mahmoud Khalil and others who have advocated for Palestinian human rights, or demonstrated against Israel’s use of U.S. supplied arms on civilian populations.

We needn’t look to D.C. to see the clumsy wielding of the censor’s cudgel. In May, the Whitney Museum canceled a performance scheduled for the 14th of that month, titled No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom, an Independent Study Program student-performance piece about the suffering of Palestinians that incorporated texts by the award-winning poets and writers Christina Sharpe, Brandon Shimoda, and Natalie Diaz. The reason given, by the Whitney’s communications office was that a previous version performed in October 2024 at the Poetry Project, co-presented by Jewish Currents, involved a participant telling audience members during the introduction to leave if they supported Israel. The Whitney canceled the event even after the ISP students indicated that this would not be part of their performance. On June 2, Scott Rothkopf, the museum’s director, announced via email that he was suspending the Whitney’s storied program. At the same time, Sara Nadal-Melsió, then the ISP’s Associate Director, learned that the Whitney had terminated her position. The National Coalition Against Censorship rightly condemned the museum’s decision.

Rothkopf and the Whitney have brought us to an alarming new place by censoring in advance, and this has resulted in a chilling effect that hasn’t lifted since. Unless resignations or further substantial dialogue take place, this decision will hang over every subsequent curatorial presentation, over every hiring decision. The clock ticks as we await the 2026 Whitney Biennial, which will be viewed not as an insight into how contemporary art responds to the present, but how contemporary art can respond to the present there. Meanwhile, Gaza is reduced to rubble, the population dwindles in famine conditions, and the genocide certifications keep trickling in.

*

In October of 2023, I was writing regularly for The New York Times as a contributing critic. I was alarmed to watch the AP and other outlets—but not the Times—reporting on Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant’s statement after Oct. 7 that, “We are fighting human animals, and we act accordingly,” referring to Gazans, and his call for a “complete siege.” This dehumanizing rhetoric seemed to suggest plans for a retaliatory war crime. I remember checking the Times website for his “human animals” phrase and not finding it each day after it was initially reported. The comment was made on Oct. 9, and was covered as news in most major outlets I was reading then. When I did first read it in the Times, it was in opinion pieces published online, by Nicholas Kristof on Oct. 11 and then by Michelle Goldberg the next day. She assessed what this portended, as did I, and stated plainly: “Such collective punishment is, like the mass killing of civilians in Israel, a war crime.”

I referenced a version of the galling phrase in the paper of record that month, too—though still not in the news section where it belonged. I tucked it in my review of the Inuit artist Shuvinai Ashoona’s large-scale drawings of hybrid human-animal figures, for I saw it in her works on the walls of Fort Gansevoort gallery before I read it the Times op-eds. Ashoona satirizes and rejects the settler-colonialist violence of viewing the Indigenous artist as a human animal or curio. In Drawing like the elephant, 2023, depicting a drawing competition scene, the artist incorporated phrases including: “winner for each animal drawing,” and then “winner for showing animals do draw.” In pointing out how Ashoona was slyly playing with, even mocking, her audience’s potential reaction to her work, I was self-consciously reflecting on where I was publishing, and quietly registering my own protest of the paper’s failure to report consequential news.

At the time, I felt like my act had all the power of whispering a secret into the hole of a tree and then covering it with mud. But, since Ashoona’s show was among the best to see in New York at that fraught moment, at least I knew that I was doing my job by recommending it to readers—even if someone in the news division was failing to do theirs. I could read in the artist’s work, in that standout show, something of what the paper I had once relied on had failed to tell me.

I don’t think every artist needs to respond to the latest injustice or shifting currents of the national mood, and I recognize also that some exhibitions are years in the making. Art can be a refuge and an escape. But as critics, rather than look away from the crisis, we must enter it and try to see clearly.

in your life?

in your life?