The first thing to know about Calder Gardens is that it is not a museum. The new $90 million Philadelphia cultural institution doesn’t have a collection, thematic exhibitions, or even wall labels. It consists of an 18,000-square-foot building designed by Herzog & de Meuron; a carefully landscaped-to-look-wild garden by High Line designer Piet Oudolf; and a rotating display of sculptures by Alexander Calder, a Philly native famous for creating the mobile.

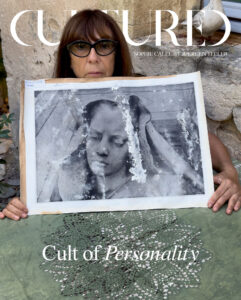

Developed in partnership with local philanthropists including Joseph Neubauer and the nearby Barnes Foundation, which is offering operational support, Calder Gardens aims to create an art space that is not for learning or doing, but rather for thinking and feeling. Ahead of its Sept. 21 opening, CULTURED caught up with Alexander S.C. Rower, the Calder Foundation’s president (and grandson of the artist), and Juana Berrío, Calder Gardens’s senior director of programs, about what it takes to build a new kind of cultural experience from the ground up.

CULTURED: Where did the idea for Calder Gardens come from?

Alexander S.C. Rower: This amazing character from Philadelphia, Joe [Neubauer], called me up and said, “I want to do a Calder Museum in Philadelphia, in his hometown.” I said, “I’m not interested in doing a museum, but I would do something else.” Calder Gardens is an experiment.

CULTURED: What does that look like in practice? What parts of the conventional museum world did you move away from?

Juana Berrío: We’re prioritizing storytelling rather than scholarship. I’m thinking about these meditation, mindfulness, and contemplation practices that we’re going to include. We’re commissioning artists to do audio walks.

Rower: There isn’t a biography available. There aren’t titles and dates available. We don’t know how agitated people will be to not have wall labels. But it’s not about the artist’s experience. It’s about what could be your experience.

Berrío: It speaks so much about the present moment—how we are conditioned by elements in our culture that tell us you cannot do things on your own. You cannot go from point A to point B without Google Maps. You cannot learn something if someone is not teaching you. We want to make sure that people feel that they can find their own tools within themselves.

I’m from Colombia, and more than 20 years ago, I had the chance to live in the forest on the Pacific Coast for several months. I noticed things about my body and my brain, like how you get attuned to particular sounds, how you isolate different things, how you respond to light. So that’s why I trust that we all have those tools.

CULTURED: Nature plays a key role in Calder Gardens. How does the landscape relate to Calder’s work?

Berrío: Every element—the works by Calder, the garden, the building—they’re all constantly moving and changing.

Rower: Calder was an ecologist. In the ’70s, when I was a little kid, I had these big discussions with my grandfather about the future of water, how water was a resource that we were losing track of. Piet Oudolf’s gardens are really specific in that they don’t just make an annual four-season revolution. They continue to evolve and step up, which is exactly what your experience with Calder’s art is [like].

in your life?

in your life?