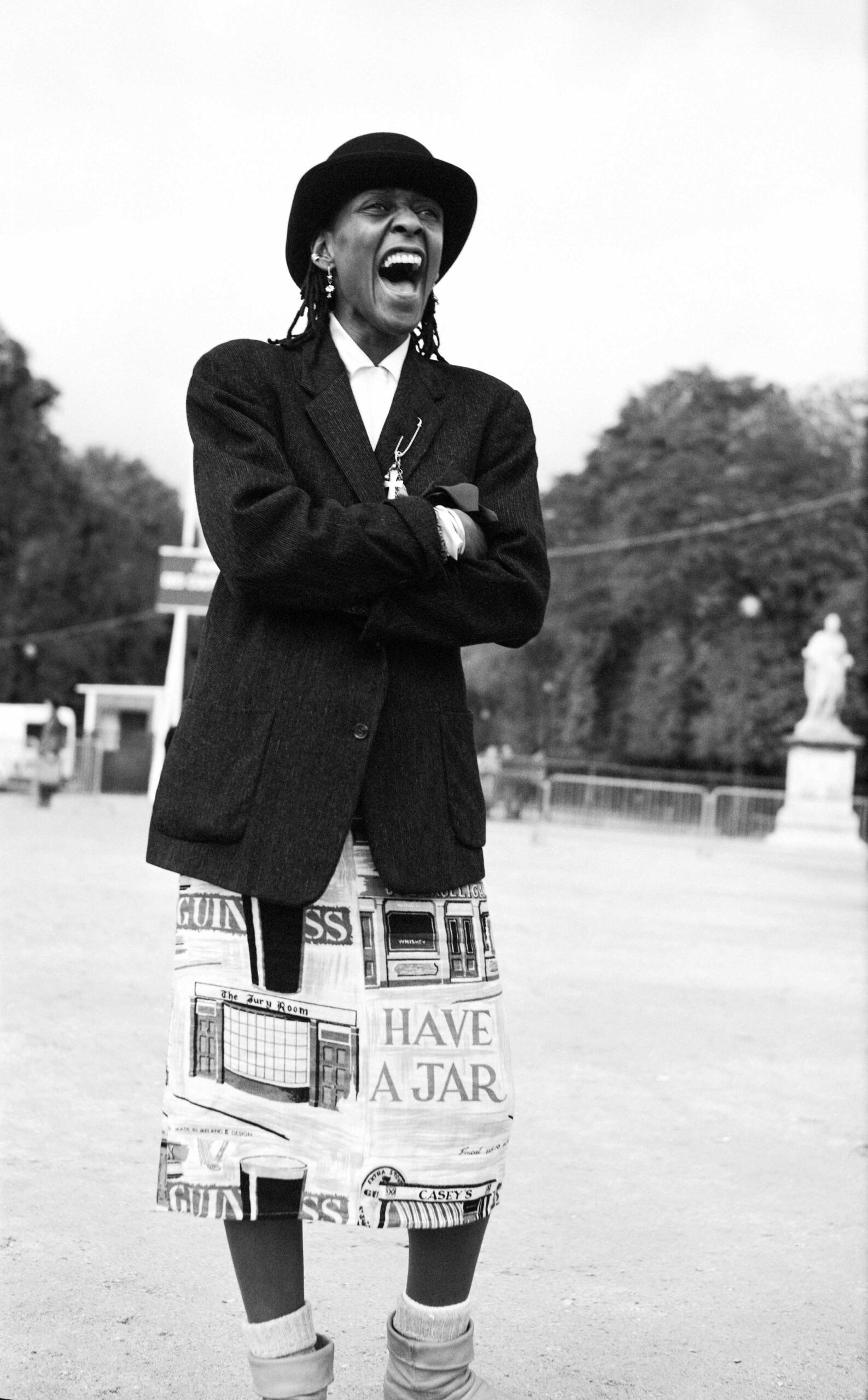

“We’re all students of Bethann Hardison,” says Tyson Beckford in Invisible Beauty, the 2023 memoir-in-film of the soon-to-be 83-year-old materfamilias of American fashion.

Beckford is of course known as the rare male model to have ascended to household name status. Hardison helped put him on the map—like she did with Veronica Webb, Kimora Lee Simmons, and a generation of faces that made their way onto runways, magazine pages, and TV screens—a few years after founding her modeling agency in 1984. The Bethann Management era followed two decades of history-making moments for the New York native, from being discovered by the streetwear savant Willi Smith when she was but a Garment District showroom assistant to walking in Stephen Burrows’s Battle of Versailles face-off in 1973. It also ushered in a whole new chapter of her life dedicated to holding the fashion industry accountable for maintaining the strides in racial diversity it had made, ever so incrementally.

The meaning of a model has changed drastically over the course of Hardison’s lifetime. She has witnessed the rise and fall of the supermodel, the advent of the casting director, and the revolving door of runway regionalism. A subset of models today are voicey, taking to platforms like Instagram and TikTok to livestream their influence with verité-ish confessionals, but few have a voice. Hardison’s Black Girls Coalition, founded in 1988 with Iman and brought back in 2014 as runway diversity waned, empowered dozens of models of color to not only speak out but stand behind each other, denouncing racism in ad campaigns as much as they rallied around homelessness in the industry.

An initiative as rhizomatic as the BGC is a unicorn in an industry that has become as splintered as it is self-centered. This May, Hardison announced a new eponymous foundation that will extend her support to discovering and mentoring emerging creatives. These days, she is as invested in the forces shaping fashion from behind the scenes—like Polo Ralph Lauren’s James Jeter or stylist Carlos Nazario—as she is in the front row. But she’s never short on opinions about the trade she revolutionized time and again.

For our September issue, Hardison sat down with CULTURED’s style editor-at-large, Jason Bolden, to parse the fate of the fashion model.

Jason Bolden: Thank you for doing this—I’m beyond excited. I want to talk to you about the culture of the fashion business and get your perspective on what’s new, what’s the same. Do you feel like modeling has found a new renaissance, or is it in a rut?

Bethann Hardison: Look, everything is changing. The great thing about the modeling industry for me is that it has found its way to be more diversified. I only deal with the racial diversity part. I don’t care about how big you are, how old you are—I didn’t come here to make those changes. I just wanted to make sure that we went back to something I had already known, racial diversity, which lost its weight because of the fact that Eastern Europe had opened up [in the 2000s]. I love the body alignment of an Eastern European girl, but when it went on for a decade, I knew my industry was in trouble.

Bolden: Your intention had really nothing to do with the business side of fashion, but just that momentum of pushing diversity translates into dollars and cents. It also gives the consumer an opportunity to see themselves, which makes them want to shop.

Hardison: I was never thinking in dollars and cents, or equity. I was only thinking intellectually.

Bolden: But it turned into a business. It helped someone like me; I got to see myself. You can’t make change if you can’t see it visually. You gave us a vision to grab onto and catapult into different careers outside of walking the runway.

Hardison: We didn’t have things in the industry called casting directors before, who began to cripple the model industry and the fashion industry. The designers and their teams used to find the models: That’s how models became muses. Yves Saint Laurent and Mr. Givenchy showed it best because they had cabines of women that they just loved. The idea of trying to put the girls of color back into the fashion industry was to make sure that whites and Blacks and everyone started to see color again. If you put that girl there, then it would also affect other industries, which it did.

Bolden: It affected my industry too. Once you start saying yes to those girls, they start having a voice and being like, “Hey, I need this particular person who understands my makeup and my hair.” It opened up a world for them to give opportunities to people like [makeup artist] Sam Fine, for example. Are there any models right now who remind you of any of those early trailblazers you championed?

Hardison: Once I start seeing that something’s okay, I take my foot a little bit off the clutch. I’m not very interested in fashion models [at the moment]. The problem with the modeling industry is that once they discover a type of girl—like the West African model—it becomes so inundated. Even though I’m happy that the girls and boys are working—and the boys are doing even better to me—it becomes a question of how much of a career are they going to have? The last hurrah that I had was when I took everyone from Imaan Hammam to Cindy Bruna out for dinner and made them into a posse. Those girls have a career. I don’t care if you’re making $7,500 a month or $75,000, a career is when you can continue to work and people continue to see you.

Some of the West African girls are coming along and you won’t remember them all. But you will remember someone like Anok [Yai] because she’s a unique, great model. She knows what she does when she hits the runway; she knows why she’s there. [Nowadays] a lot of girls don’t know why they model. You’re almost like an actor; you have to have an intention on that runway. I was moaning with the CEO of Gucci not too long ago, telling him how I just hate when these girls walk through the room stomping like they’re rushing to the gate of an airport. There’s no purpose.

I’m more interested in the creatives who continue to gently propel what we need to see as people of color—because there are no models out there that are going to do what Bethann Hardison did. There’s a young man [at Ralph Lauren] that I’m very taken with, James Jeter. His story is wonderful and [so is] how he’s been allowed to work within Ralph. Ralph discovered him [working] in the store and had him come to the corporate office to work with him. To come into the creative area, he had to prove that he had something to give. Now, he’s the young man who did the collection that [partnered with] HBCUs and honored Oak Bluffs and Martha’s Vineyard. That to me is so significant because it’s storytelling.

Bolden: To hear these stories of people like Ralph, one of the pillars of American fashion, reaching back with eyes wide open [is incredible].

Hardison: He’s never been asleep. People made the mistake of saying Tyson Beckford was the first Black model for Ralph Lauren. That’s so far from the truth. I go with a big broom everywhere I go, sweeping up the incorrect information… I have a real issue right now; I’m one of those people who would like to go to schools and tell fashion students to please not be a designer. There are so many fucking fashion designers out there, and most people don’t even know that fashion is a true trade.

Bolden: But everybody is chasing fame. In the world of social media, everyone has an opinion, but they don’t understand how we even got there… What you’re saying makes me really excited to push and ask questions constantly in these spaces—uncomfortable questions—and when I feel like I don’t see what I want to see, then it’s up to me to push that boulder uphill.

Hardison: I’m still here to help the boat ashore. I’m glad that I’m asked to be part of many things. But at the same time, I’ve always been a visionary and a nonconformist. I tend to go to the left when everybody is going to the right. Let me ask you a couple of questions. When you first started thinking about what you wanted to do, did you ever think, Oh, I would like to be a stylist?

Bolden: I never even knew that was a job. I’m born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri. I thought there were two ways to do fashion: You worked at a really fancy store or you became a designer. I came into the business by selling vintage clothes. I did a pop-up in New York by accident, and I had no idea what I was doing. I just knew how to curate beautiful clothes with a small amount of money, and I could tell you the history of the brands front and back from Claude Montana to Bill Blass to Ossie Clark. It was an accident!

Hardison: It’s never an accident! Stop with those silly words. I don’t know anyone who is now doing what you all do that didn’t come out of some sort of circumstance… But when you do the work you do now, you’re still doing it from the point where you started: pure joy.

Bolden: I’m at a really amazing place where I’m seeing it in a different light because I have a child. I get to show my child what it feels like to be in love with something that you do, you know what I mean? And the work is never done.

Hardison: We didn’t come here to fix anything. When you left St. Louis and did your pop-up, you didn’t come in thinking, I’m gonna [change the world]. But sometimes we are meant to do things. In this particular case, the industry has changed. The only good thing was being able to make the entire international fashion industry embrace racial diversity, which was the most important to me. If there’s not as many Black girls or boys on the runway as there were before, it’s because it’s finding its place. Sometimes you gotta get the herd to be curated, so that those who are meant to survive it will.

in your life?

in your life?