When the Museum of Modern Art in New York established its New Photography series in 1985, photographs could only be edited in the darkroom. Now, as the series celebrates its 40th anniversary, most of us carry powerful cameras—that also edit and store thousands of images—in our pockets. Fittingly, the eye and skill of a keen photographer have never stood out more. MoMA’s latest installment, “Lines of Belonging,” opens Sept. 14. Featuring 13 international artists and collectives from four cities, the show is a testament to the enduring power of a well-captured image. Here, three of the participants reflect on their contributions.

Sandra Blow

Sandra Blow captures the thriving queer, artistic, and nightlife scenes of Mexico City, where she lives. Trained in advertising, her photography spans fashion editorials and snapshots of daily life.

“I took this photograph in Mexico City. The person in the image is my friend Tony, a French tattoo artist. The context was simple—like many of my photos, it was just a fast, fleeting moment. We were at my home in Colonia Roma, and Tony wasn’t wearing a shirt because it was a hot day. I grabbed my camera and asked to photograph his Chanel tattoo. I loved the contrast of luxury branding with tattoo art. I shot it on expired film, which adds to its feeling. Though I haven’t seen Tony in years, this image makes me feel we’re still friends.”

L Kasimu Harris

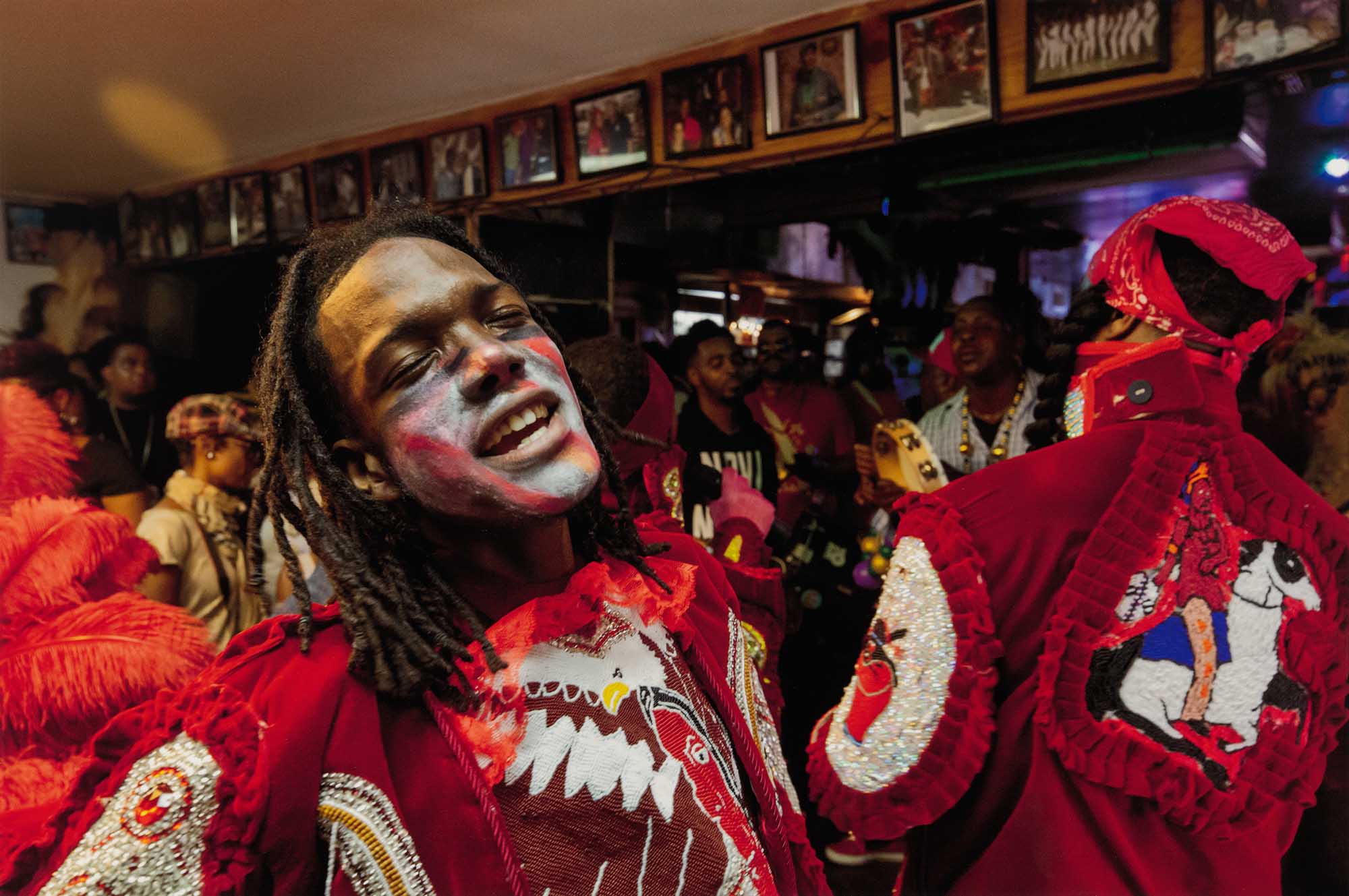

L. Kasimu Harris strives to tell the stories of underrepresented communities in his native New Orleans. His photographs are in the collections of institutions including the New Orleans Museum of Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

“Marwan Pleasant is a fashion designer by trade, a Black Masking Indian by blood, and a flag boy in the Golden Eagles by choice. I made photographs as he and other members of the tribe suited up at the home of the grandfather, ‘Big Chief’ Monk Boudreaux. It was Mardi Gras morning 2018, and blocks away from the marching bands and floats. Their tribe meandered [through] the streets in traditionally Black neighborhoods of uptown New Orleans. They chanted and greeted other Indians in a contest of who sewed the prettiest suit of beads and feathers. The suits are heavy and this city is perpetually humid. Respite was in Sportsman’s Corner, a venerable Black-owned bar. Inside, the Indians resumed singing, and Pleasant was in the throes of a spiritual transition. I moved closer. Beyond the peak moment, the image is about access, preservation, and a bold declaration for Black culture: I was here, I am here.”

Prasiit Sthapit

Prasiit Sthapit is a visual storyteller based in Kathmandu who photographs societies at the borderline. He is also the director of Fuzzscape, a multimedia music documentary project.

“For decades, Susta lived in limbo—no bridge, no electricity, poor schools and health care, and every monsoon, hundreds of hectares of land used to erode. When I first visited in 2012, two huts sold tea and fish; a year later, they had vanished into the river. Each year, the river crept closer. Retaining walls built in 2016, shown here, signaled change, followed by a bridge completed finally in 2024. It brought electricity, tourism, and market access. Locals speak of transformation. I, however, am inclined to be a little more skeptical. If there’s anything Susta’s history has shown us, it’s that hope is best leavened by caution, but hope is necessary and, in the case of Susta, even powerful.”

in your life?

in your life?