Pole dancers, masked mourners, a fisherman, and an image of the artist herself are among the painted figures here in Ambera Wellmann’s Bushwick studio. It’s a lot of bodies for a body of work that she set out to make without any. The artist laughs as she moves canvases aside to reveal others propped up behind them, telling me about the self-issued challenge, acknowledging that she changed course—re-embracing figuration—rather quickly.

We meet in late June, and this is not an et voilà event. She is in the thick of it, showing me almost-finished and maybe-finished works, and mentioning others she’s not yet started. Her dog, Chicken, a Chinese Crested, barks for treats while we talk, and the artist holds a sprig of linden blossoms that I plucked on my walk from the train to her nose, taking deep breaths. Wellmann is preparing for a pair of New York shows, both opening on Sept. 5. One will be at Company, the adventurous, esteemed, and queer-focused Elizabeth Street gallery that she has worked with in New York since 2020. The other, her debut for Hauser & Wirth, will take over the mega-gallery’s Wooster Street space.

The concurrent exhibitions, and the joint representation they celebrate, propose a new model for the gallery system—an ecosystem where big fish don’t always eat the little (or medium-sized) ones, and where artists, fingers crossed, can benefit from the best of both worlds. More importantly, at least as far as our conversation is concerned, the two very different spaces offer an opportunity to stage complementary shows. (It’s a 13-minute walk between the venues, making staggered receptions doable.)

On Wooster Street, she’ll hang a group of new paintings, including an epic centerpiece, on white walls. Company, on the other hand, is “a great place to be totally unhinged, go crazy, be disgusting, whatever,” she confides, a little giddily. That show’s pièce de résistance will be a charcoal mural drawn directly on the wall—something she’s never done before.

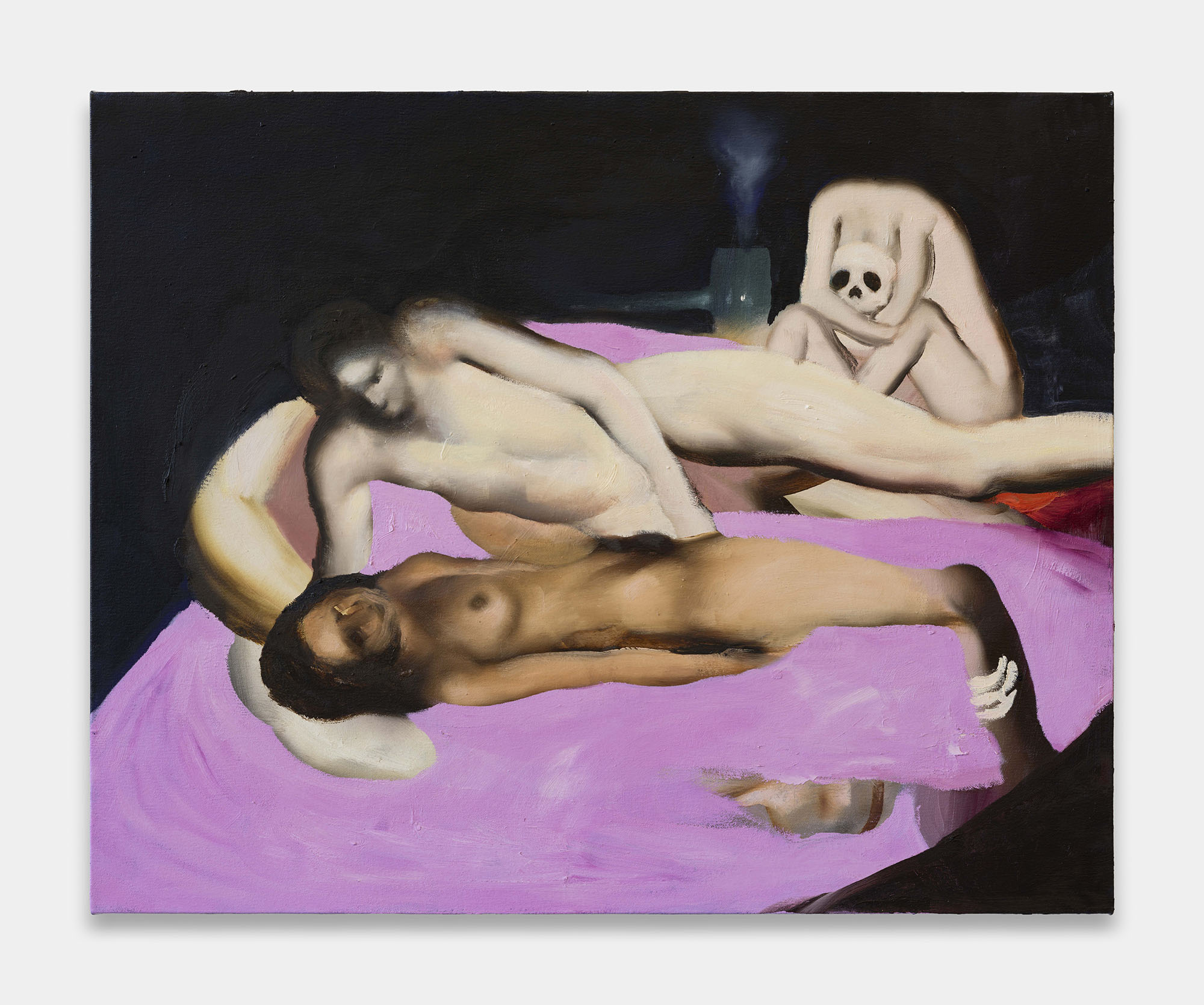

Wellmann is known for her collage-like and hallucinatory paintings, feats of spatial impossibility rife with internal inconsistencies of perspective and scale, populated by unmoored elements drawn from a lexicon of striking, semi-mythic imagery: Glistening fruit, watchful animals, and women fucking are frequent subjects. The artist’s sex vignettes—her soft-focus but graphic blazes of sweaty torsos and pliant limbs—are fan favorites to say the least, but her appetite for them has been tempered by a certain skepticism recently. The desire to move away from bodies, however fleeting, is partially due to “feeling frustrated with figuration as an art-world trend, and, in particular, with ‘queer figuration.’ I began asking, Are we making this for a straight audience? Who is this for? It started feeling almost conservative, in a funny way.”

I know what she means, I think. Most pessimistically: Figurative painting has become clichéd as the mediator par excellence of identity, inadequate for the task of representing difference (or worse, guilty of flattening it), and cheapened by its use as a fast and dirty, easy-on-the-eyes means to diversify a collection (though I’m hesitant to cast aspersions on the impulse in this radically regressive moment). But, I also think, setting aside the most banal practitioners of so-called or market-defined queer figuration, the “trend” means little when you look at painters, or at paintings, one by one.

Wellmann’s unease is understandable, though, and she gives other reasons for pushing herself into new terrain as well. She gets bored easily, she says, and “as soon as I feel like I’m painting something that people expect of me, or that I expect of myself, the potentials for surprise, change, transfiguration—the things most important to my practice—have disappeared.”

The artist, now 43, grew up in rural Nova Scotia, in the seaside town of Lunenburg, without much exposure to art. Two postcards Wellmann’s mother had—reproductions of a Blue-Period Picasso mother-and-child and Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son—had an outsized influence on her as a quiet child living in a violent household, though their value to her lay less in their aesthetic qualities than in their role as hopeful examples of how one might have a voice without speaking. (That said, it’s easy to find Goya in the most surreal, ravenous, and shadowy passages of Wellmann’s work).

Still more profound, perhaps, was a gift she received when she was 5 or 6: a tube of black oil paint. It was like “a key to the universe,” she remembers. It follows, from her enduring wonder and passion for paint itself, that the erotic content of her work isn’t confined to the kinds of figures or acts that appear. There’s an anarchic volatility to the compositions, a sense of churning, smoldering flux, separate from the question of imagery.

When we discuss the ways that her paintings sometimes come together at the last moment, Wellmann pulls out an as-yet-untitled crimson canvas, slated for her show at Company, to make her point. (The picture brings to mind Pierre Bonnard’s The Red Cupboard, 1939, set aflame.) She explains how a rash act of redaction resolved it: There’s a figure somewhere in there, concealed by the burgundy gloom of the still life’s background. “There’s a sense of atmosphere now, so palpable you can almost imagine breathing it,” she says, still awed by the effect.

She turns around to face a more recent two-panel work on the wall behind us, People Loved and Unloved , 2025—another composition of thrumming, scarlet atmospherics—that will no doubt be a standout in her Wooster Street presentation. It was initially going to show a debaucherous dinner party; as she finished it, she thought, I think it needs to be a strip club. She added pole dancers—descending nude and upside down—into the chaotic mix of messy tables and pensive, spectral, or staring guests. “I wanted the painting to feel like drunkenness … as though you’re seeing double. I wanted it to feel like a k-hole.”

Despite all this, the appearance of spontaneity, heat, and speed is somewhat deceptive: There’s as much—or more—attention to craft and art history, more scraping (or sanding) away of paint and repainting, as there is furious abandon. Pentimenti provide a material record of a halting or multistage process, speaking to a slower pace, as does the enchanted illusionism Wellmann perfected when depicting porcelain vessels and figurines in the somewhat quieter, cooler work of the late 2010s—when she was finishing graduate school in Ontario, and just after.

Unfussy but precise, the technique endures in her repertoire, mingling with looser and more abstract painterly modes when she renders other, non-ceramic objects. Apples catch the light in haloed dots and razor-thin lines of bright white (she paints lots and lots of glossy, scattered apples); musculature is defined by gradations of color that appear, somehow, both smeared and airbrushed. She bridges the brittle, delicate, glazed translucency of porcelain and the glow of warm skin with a dreamy seamlessness that can’t be rushed.

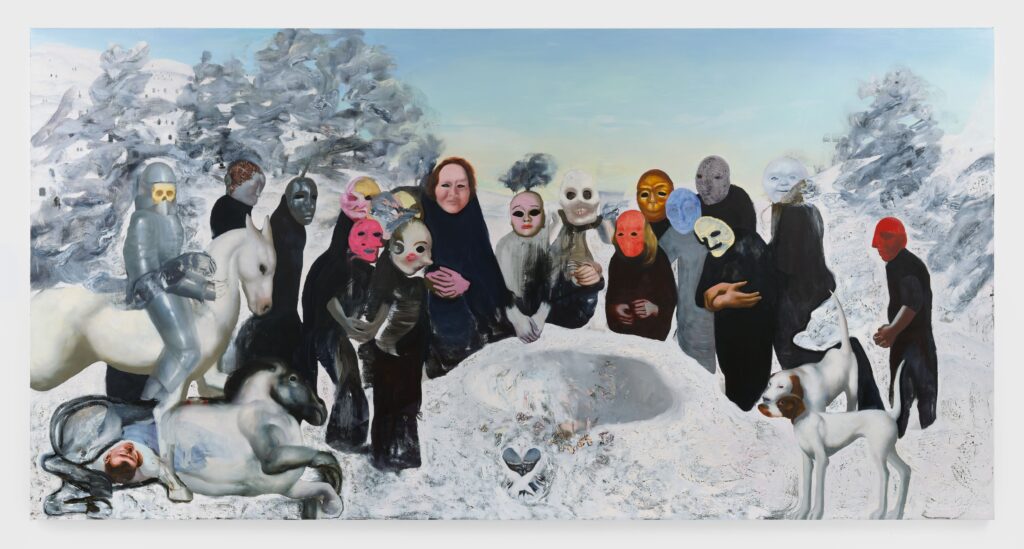

We begin and end our visit by looking at the largest work in her studio, the 18-foot composition Death Masks Eternity, 2025, after Courbet’s Burial at Ornans, 1849–50. Wellmann’s supernatural, wintry take evokes not just the gray-sky gravitas and ritual of the famous panoramic group scene, but also the French artist’s abandonment of idealized Romantic subjects for a steely Realism—the kind of artistic rupture that perhaps befits our too-real times.

While not the only moment when climate grief surfaces in the paintings assembled here, it’s the one that spurs Wellmann to articulate her interest in it. She’s concerned, in her art, with the way the accelerating crisis changes our “experience of time and understanding of death,” she says. Recounting a conversation with her ex-wife, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger (“like proper lesbian exes we still talk on the phone for three hours a day”), she says the catalyst for the work—which will be the main event of her Hauser & Wirth show—was an observation from the Mexican painter: “When we were young, we felt like we were moving toward the end of lives, toward death. Now, it feels like it’s coming toward us.”

Just like the original 19th-century painting it references, it’s unclear in Death Masks Eternity “who or what” is being laid to rest. But Wellmann is not coy about why she chose to blanket the cemetery in white. She tells me that some winters during her childhood, there were five feet of snow—now there’s none. The painting’s central void—an icy crater—gathers the dark-robed and disguised mourners (as well as a pair of beautiful hunting dogs and the skeletal horseman of a tarot deck’s Death card) in a semicircle that the artist and I, standing before it, complete. It’s captivating, but not entirely comfortable, to be roped into this ambiguous ritual. The feeling is emblematic of the risk and mystery in Wellman’s work generally, though.

After hours of talking, I still have questions—what does she mean, exactly, when she says that Company’s space is a great place to be “unhinged” and “disgusting”?—but I know it’s futile to press her on something that’s TBD. It’s enough to be in the presence of her excitement—I’m inspired that an artist so self-scrutinizing and careful is also so confident in last-minute magic, in work that doesn’t yet exist.

in your life?

in your life?