Vicky Krieps never imagined being an actor. As an 8-year-old growing up in Luxembourg, she remembers watching Beauty and the Beast—not the Disney version, but the surreal 1946 one by Jean Cocteau—and longing to be a part of it. “But I had no idea how,” she recalls. “If you’re from there, you don’t dream of becoming a film actress. Those people come from London, or Paris, or New York.”

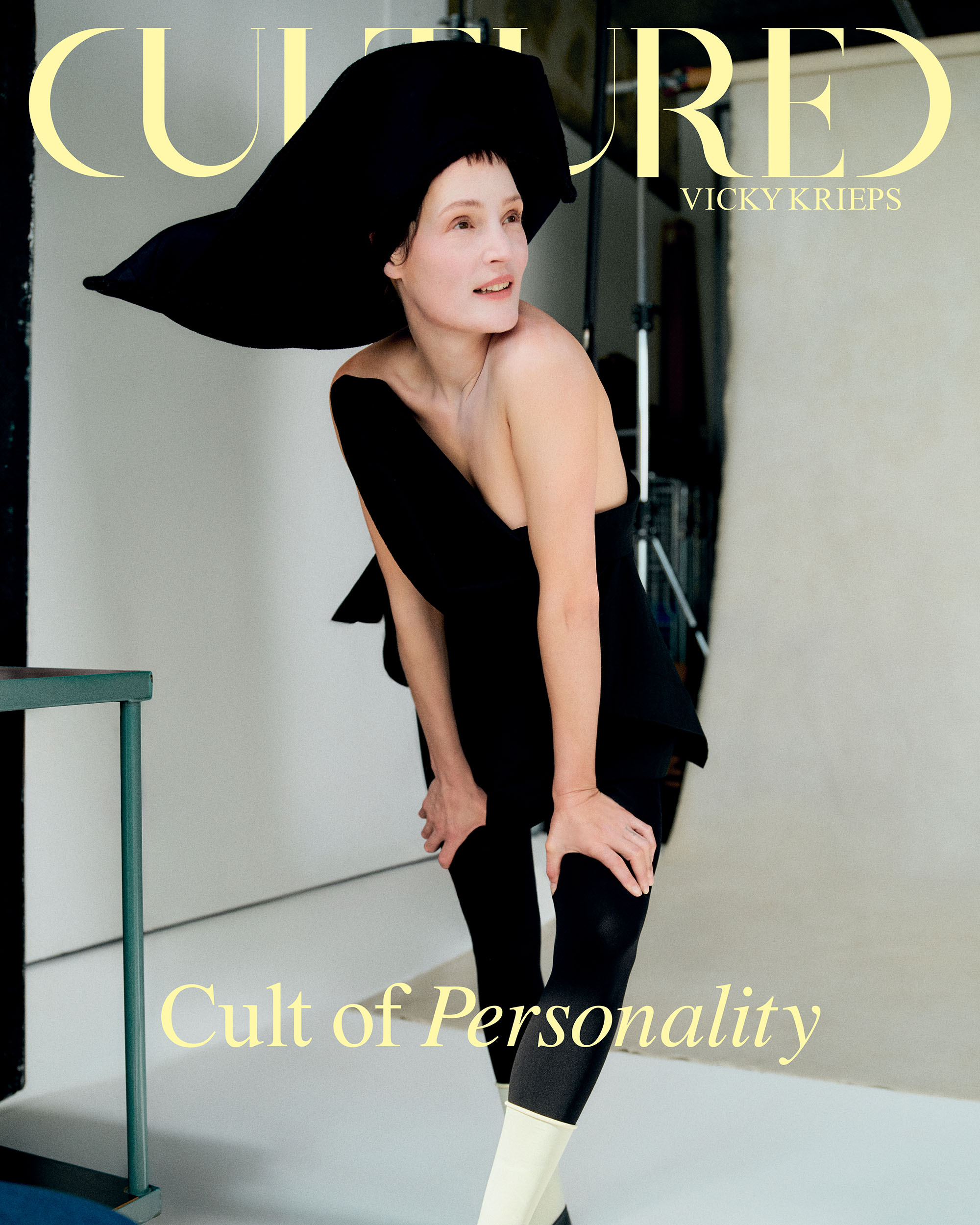

The ominous romanticism of Cocteau’s fairytale rendition feels like an apt origin story for Krieps, who, nearly two decades on screen and a Cannes Best Performance award later, has earned a reputation for skirting the expected to conjure an off-kilter mood across her steadfastly independent filmography. In her performances, there inevitably comes a moment when the 41-year-old actor seems unreachable, detached—her cheeks flushed, dark eyes drifting just above the fray. These scenes reveal her eerie magnetism: She’s not just present in the emotional gravity of the moment, she’s thrumming with it.

By this point, most cinephiles know the hallmarks of a Krieps role: women confronting moments of rupture or unrest, characters who resist intimacy in order to safeguard knotty inner lives. The actor is drawn to these parts for reasons she can’t quite explain. “It’s nothing to do with ‘who’s the director, what is the budget, or who is in it,’” she muses over the phone. “I myself never feel like I’m at the steering wheel.” In this case, her meaning is both literal and figurative: She’s riding shotgun with her husband Lazaros Gounaridis on a road trip through Europe when we speak, a brief moment of calm before the maelstrom of festival season.

“Jim Jarmusch is my hero. I would’ve done anything he asked.” —Vicky Krieps

This fall marks a kind of supernova moment for Krieps, with three major premieres that reveal the depth and range of her enigmatic sensibility. First, there’s the theatrical release of Love Me Tender, an adaptation of Constance Debré’s cult memoir, which debuted at Cannes to strong reviews. In it, Krieps plays a lawyer mother fighting for custody of her young son after coming out as a lesbian. In Yakushima’s Illusion, the long-awaited return from Japanese auteur Naomi Kawase, she’s a hospital worker coping with the disappearance of her lover on a volcanic island. The film is heavy on atmosphere and light on plot—Krieps hasn’t seen the final cut, and can’t make heads or tails of it just yet.

Then there’s Father Mother Sister Brother, the latest from Jim Jarmusch and the centerpiece of the New York Film Festival this month. A triptych that follows adult children as they reckon with aging parents, Krieps stars opposite Cate Blanchett and Charlotte Rampling as siblings visiting their novelist mother in the film’s Dublin-set second installment. (Krieps sports pink locks in the film, an uncharacteristically overt transformation for an actor who tends to look like herself onscreen.)

The Jarmusch project is a quietly momentous milestone for Krieps—a collaboration with a director she idolizes, and a role that promises to introduce her to a wider audience without compromising what she values. “Jim Jarmusch is my hero,” she gushes. “I would’ve done anything he asked.” She first encountered the laconic No Wave director as a teenager watching Stranger Than Paradise at her local cinematheque. “I thought this was the coolest thing on the planet,” she continues, describing the scene where Eszter Balint trudges through an empty Lower East Side with a boombox blasting Screamin’ Jay Hawkins.

But more than music or mood, it was Jarmusch’s refusal to rush, his willingness to let a scene drift into place, that left an impression on Krieps. It’s something she prioritizes in her own craft. “I like to just stop the train for a minute,” she says of her tendency to impose a pause, literally, onscreen. “It’s a form of resistance to this system that tells us everything has to move forward: the plot, the money, the house, the car.” Most movies, she observes, exist to entertain. “You need tragedy, you need a joke, all the elements to try and catch everyone’s attention.” The Jarmusch project, on the other hand, gave Krieps the chance to ask, “What happens if we don’t try to do that at all?”

“The more perfect I am, the less room I leave for the audience.” —Vicky Krieps

Krieps is similarly contrarian when it comes to accents, which she refuses to perfect—more out of conviction than carelessness. “If I’m given an exercise and I understand how to do it, something in me resists giving that last 10 percent,” she observes cheekily. She notes, for example, that she’s just a few tutoring sessions shy of speaking unaccented French, but prefers to savor the subtle imperfections of her diction. “Everyone has an accent from somewhere,” she says. “The more perfect I am, the less room I leave for the audience.” Krieps holds fast to these principles, even with her idols: Her character in Jarmusch’s film is meant to be English, but bears an alluring trace of the actor’s continental inflection.

Though her characters occupy wildly different universes, Krieps argues that they share a common yearning. “They’re trying to break free,” says the actor, who often describes her work as a means of gnawing away at something fundamentally human. “I feel a need to research humankind,” she adds. “Why are we good? Why are we bad? Why do we fight? How do we love?”

Her supporting turn in the upcoming third and fourth seasons of Ryan Murphy’s true crime series Monsters, which delves into the story of the serial killer Ed Gein and the 19th-century patricidal axe murderer Lizzie Borden, respectively, falls along the same continuum. “These monster stories, they’re always asking why we are the way we are, and how we transcend that.”

Despite her coveted filmography and stacked fall slate, Krieps remains willfully out of step with the machinery of fame. She’s noted before that she comes down from a project by writing songs—a private way of metabolizing the emotional residue of her work. “It’s a relief,” she says. “Even if the song doesn’t answer the mystery of who the character was, at least I can let go of something.”

“Even if the song doesn’t answer the mystery of who the character was, at least I can let go of something.” —Vicky Krieps

But when I ask if she’d ever release them publicly, she stops me short. “You make the music and then what—it has to go online? Why? It wasn’t made to be sold.” I change the subject, asking what kind of project she wants to take on next, now that she can do anything. The answer, predictably, surprises: “Probably a silent movie,” she says, pausing. “Mm-hmm. Silent, black and white. I would love that.”

Purchase your copy of Vicky Krieps’s Art + Fashion issue here.

Creative Direction by Studio&

Hair by Keisuke Terada

Makeup by Bea Sweet

Head of Production by Kit Pak-Poy

Production by Victoria Watkins

On-Set Production by Natalie Stenier

Lighting Direction by Ivano Pagnussat

Project Management by Chloe Kerins

Motion by Joel Kerr

Styling Assistance by Cydney Eden Moore, Sofia Allegue Piriz, Cliona O’Sullivan, and Abi Wood

Hair Assistance by Yasemin Hassan

Lighting Assistance by Kayla Middleton

in your life?

in your life?