Every Nathaniel Mary Quinn work is an exercise in excavation. The Chicago-born artist is a material alchemist—manipulating oils, pastels, and charcoal into haunting portraits—and a memory worker. Many of the moments in time Quinn evokes come from his own singular upbringing: At 15, his mother passed away, and he was left to take care of himself following the sudden desertion of his other family members. He spun fragmented recollections of these years into evocative compositions that have landed in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Broad, the Art Institute of Chicago, and more. This fall, Quinn is opening his fifth solo show with Gagosian, “ECHOES FROM COPELAND,” which filters touchpoints of his life through a 1970 novel by Alice Walker, The Third Life of Grange Copeland, about three generations of Black Americans living in the South.

Ahead of the opening on Sept. 10, Quinn sat down with CULTURED’s Arts Editor-at-Large, Sophia Cohen, to parse through his novel inspirations.

You have your fifth solo show with Gagosian coming up. You also had a monograph published by Gagosian last year, the first comprehensive survey of your work to date. You’re hitting a cool stride in your career, and you’re exploring new things. I’d love to hear how this show differs from the other shows you’ve done at the gallery, and how you’ve evolved to this point in your career.

This show is a terrific development in my career. I’m excited about it, and at the same time, profoundly nervous, but that is often the case whenever I am preparing to mount a solo exhibition. This show is different from previous exhibitions because it is based on a novel by the author Alice Walker, called The Third Life of Grange Copeland. It was published in 1970, her first novel. I read this book twice several years ago, and it made an indelible mark on me.

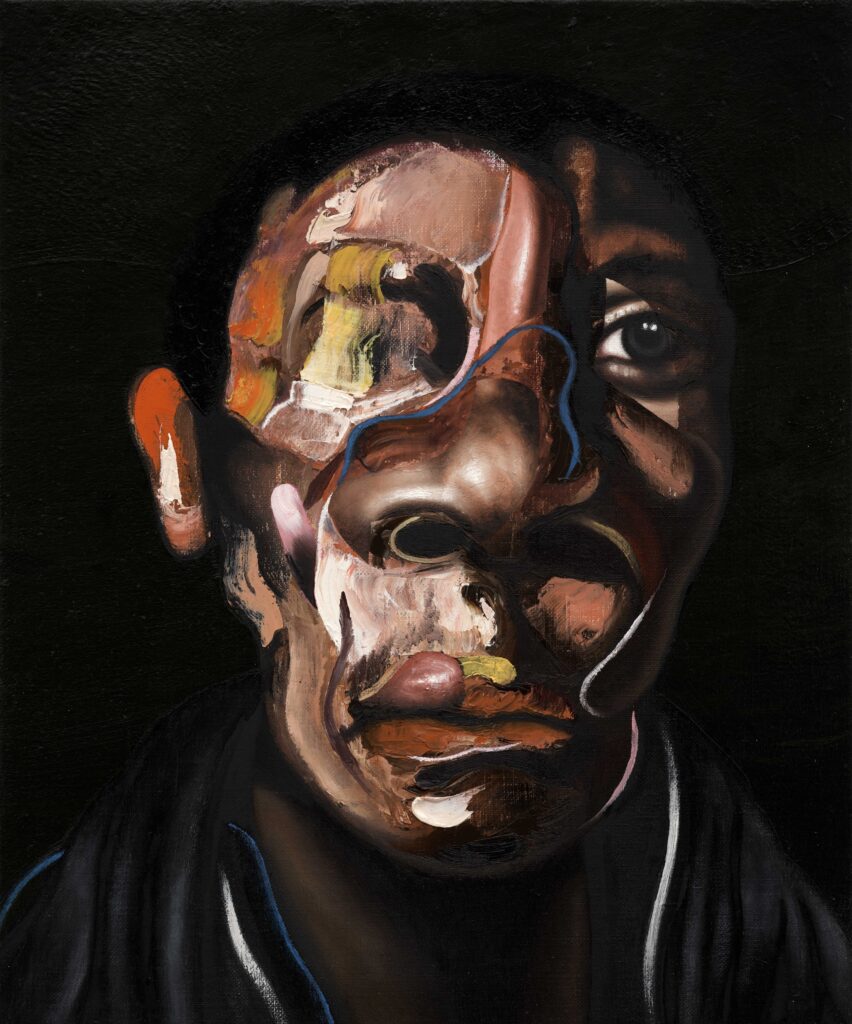

Now, I’m making this show, a suite of paintings as reflections of this book, as an ode to her incredible writing as an artist. In addition to the works—all inspired by the book, the characters in the book, and the stories and the themes that permeate this novel—I am also continuing my exploration of the marriage between abstraction and the figure as informed by my continued investigation into the works of Francis Bacon, specifically based on my direct experience of seeing two of Francis Bacon’s exhibitions in London, at the Royal Academy of Art and the National Portrait Gallery. Both of those exhibitions serve the purpose of transforming the lens through which I see my studio practice.

How did those shows transform your practice?

As most people will probably know, Francis Bacon was an abstract figurative painter and a beautiful artist. What struck me about his work was that many of the decisions he made in his paintings solve a lot of problems, especially as it relates to how he placed figures within a pictorial space and how he made use of lines as a means of denoting architecture and environment, both external and internal. I wanted to find a way to dive into that space myself. But I’m not a landscape painter. I’m not a cityscape painter. Of course, I am not Francis Bacon. I wanted to find my own convictions behind making such a move in my practice.

This book helped me to do that because Walker is not didactic in her prose—she doesn’t spoon-feed the reader what the characters look like or the environments in which they live. She does a really good job explaining the conditions of these characters, so you get a good sense of whatever oppression they contend with, or trauma, or hardship. That allowed for the explosion of my own imagination. The book is not a blueprint description of anything, but it’s literal enough that it allows for an emotional connection to the themes, the characters, and the environment. This gave me the appropriate platform to introduce space, environment, cityscape, landscape, and to be more playful in creating bridges between abstraction and the figure.

People often mistake your work for collage, but it’s not collage. Why is that distinction important to you, and how do you use layering in these abstract works to convey the portrait?

In the process of making my works, I don’t think about collage at all. What I am thinking about is how to bring together disparate parts into a whole, to create harmony with different parts that don’t seem to fit together, because that’s the way one’s own identity is constructed. It’s constructed with different experiences that don’t have a seamless fit, but you must contend with them, you must face them.

In this body of work, I wanted to find a way to blend these disparate parts without the strict, stock demarcation of lines. Line here is important because the most eloquent solution I was able to muster was using line as an adequate replacement for the sharp edges that were in my previous works, which led to the discovery of a process I would like to call paint-drawing—a combination of painting and drawing at the same time. Drawing is my first love as an artist. While these are paintings, I did not want to abandon my admiration for drawing, or more specifically, my admiration and love for lines.

You’ve been talking about the layering of ourselves. I know a lot about your biography and your journey as an artist, but at this stage, with this new body of work, what role is your biography playing in this particular story, if any?

There is a strong departure from my biography, no doubt about it. This show is giving tremendous attention to my investigation and rereading of Alice Walker’s book. There are two paintings that are a direct link to my upbringing in Chicago. But this book offered me a pathway into something about my family that I never knew about. I have no working knowledge of my mother’s upbringing or what life may have been like for her when she was a teenager. My mom passed away when I was 15, so I couldn’t ask her these questions. But I did know that my mom was from the South. She was born in Mississippi during a particular era in American history. And this book offers a glimpse, or at least an entry, into what may have been the lived experiences of my mom. So I found solace in that.

One theme in the book is this African American family that wanted to go North to escape the oppression and the terror of life in the South. And sure enough, my mom was a part of that journey and made her way to Chicago. That’s the way I made the link between my life and what represented hope for the prospective future of the characters in the book.

I know that you added your mother’s name, Mary, to your own, so that her name will be carried on as you continue to build on the life that she started for you. It’s beautiful to hear how you have been an extension of that.

I never grow bored talking about this because, of course, she’s my mom, and seeing my name on any institution’s wall, even the monograph that Gagosian did—that beautiful monograph on the cover has my name, but has my mother’s name, too. I am now entering spaces and having experiences that my mother could never fathom, that would seem like a complete fantasy to her, like science fiction. She’s not here, but her name lives on through me. And this woman, who was once arguably a nobody—she was poor, she had no education, she did not have those material accomplishments—was a lovely woman. She was the best mother I could ever imagine having, and now her name lives on through me.

Although this body of work is a departure in leaning on this book, there are these themes that are so inherently you in this work.

In all of my work, in the way I construct my figures, there’s always this rippage, this push and pull, this cut and slice and blending back together. All of that is a reflection of my childhood experiences of being abandoned by my family, trying to find a way to resolve those feelings of separation and abandonment. My mom’s physical body. My mother had two strokes, so she was crippled. My earliest understanding of the human form is a reflection of my mother’s physical body. All my figures, in many ways, reflect the body of my mom.

A lot of us walk around in this world with a lot of ourselves displayed for everyone to see. You make that a very beautiful experience in your art form.

There’s nothing I could think of doing that could give me more joy than making art. You work for hours on end trying to create the best possible works from a place of sincerity, honesty, and truth, being vulnerable and coming face-to-face with your own fragility. I would argue that vulnerability, doubts, and insecurities are as much artistic tools as oil paint. So I do not present myself as the biggest, baddest thing walking around because that’s not true. I do not give any impression that I am superior or something like that, because that’s just complete nonsense. Those are nothing more than whimsical, insecure belief systems that have no basis in reality. You are a combination of disparate experiences, which have formed you into who you are.

Like an athlete, any master of their craft develops a system to get into the right mindset. How do you structure your days?

I live according to a weekly schedule. My studio practice is very simple. I wake up at 9:30 a.m. Before 12 p.m., I have a cup of coffee with Donna, my wife. We talk about things. I work out from noon to 1 p.m., and then from 1 p.m. to 2 p.m., I read or do research. Then from 2 to 5 p.m., I have my first block of working in the studio, a three-hour block. From 5 p.m to 6 p.m., I eat lunch: normally, one-third cup of oats, one-third cup of strawberries, one-third cup of blueberries, and a half cup of oatmeal. That’s all I eat. And then from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m., I work in the studio again. From 8 p.m. to 9 p.m., I have my dinner, which is normally three ounces of salmon and a cup of broccoli. And then from 9 p.m. to 11 p.m., I work in the studio. I take a 15-minute break, and then from 11:15 p.m. to 2 a.m., I work in the studio. This is what I do every day.

I’m impressed with the healthiness of your meals.

It’s important that I work out every day, Monday through Friday. I lift weights and I do HIIT [high-intensity interval training]—it’s a lot of cardio work combined with weightlifting. I try to eat no more than 2,000 calories a day because my body is my instrument. I have to keep my body good and strong, so I can work for those many hours standing up on my feet every day. I think it’s important to give copious attention to both your physical and mental health. I have a therapist I see twice a month.

My first daily accomplishment is making the bed. And then working out, doing something really difficult with your body, and doing it from beginning to end with all the strength you can muster, is also a great sense of accomplishment. I go into the studio ready to conquer the day. There’s no mediocrity in that. It is non-negotiable. You go in and you give it your best—your very, very, very best.

in your life?

in your life?