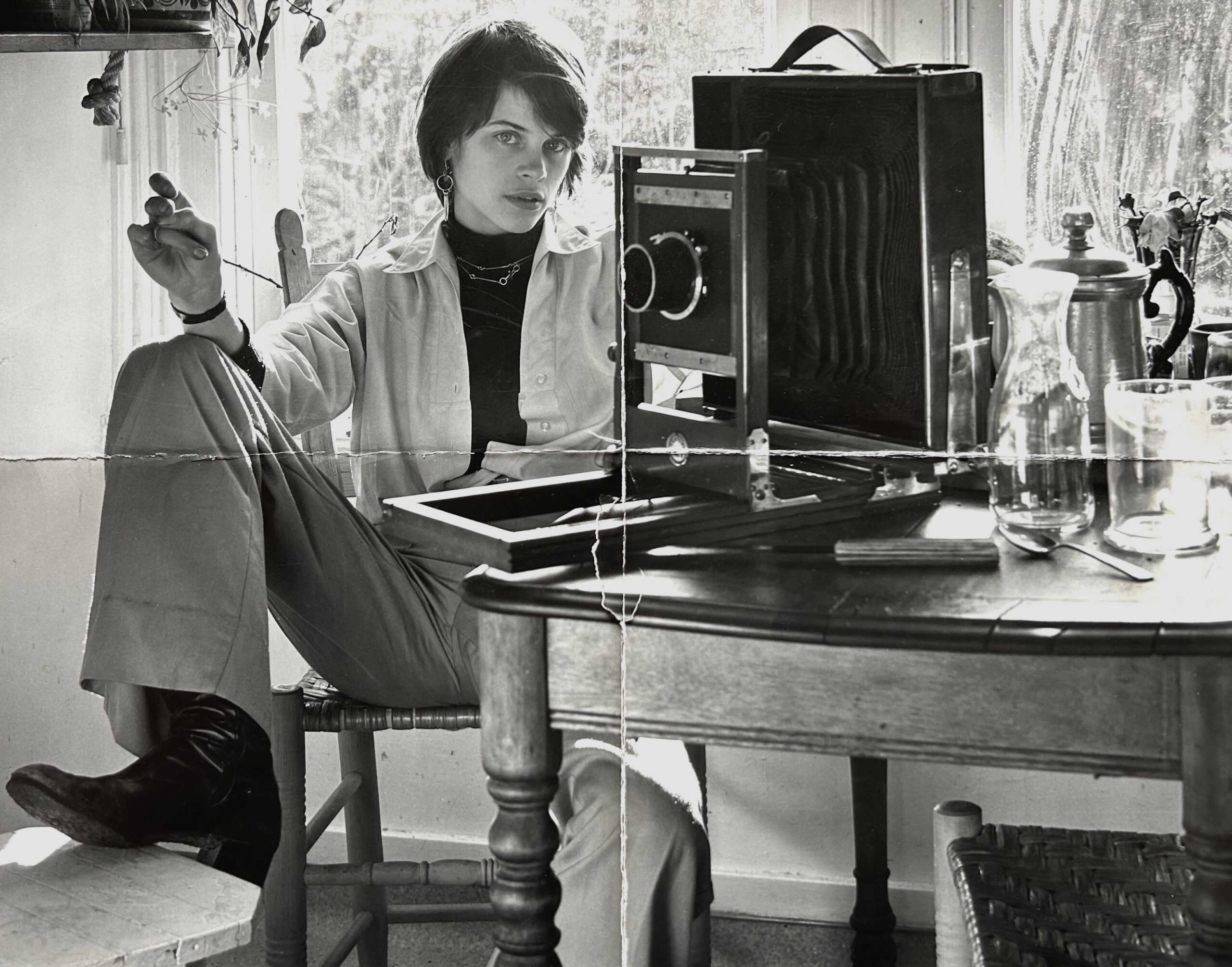

The title of photographer Sally Mann’s new book is revealing on two fronts. Art Work is, of course, what the celebrated creative produces. In 2001, she was named “America’s Best Photographer” by Time, and her intimate, unflinching images are held everywhere from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. But as Mann, 74, clearly outlines in this follow-up to her National Book Award finalist memoir Hold Still, making art is also a lot of work. Between scans of journal entries and image outtakes, Mann parses her career highs and lows. Best known for black-and-white imagery of her family and the Southern landscape they occupy, Mann has managed to divide critics and continually push herself to new territory. Here, she shares what she hopes the next generation will learn from her unsparing account.

CULTURED: You’re reflecting on a career, and sharing advice that you’ve picked up over the years. What does it feel like to reach that period?

Sally Mann: You mean what does it feel like to be an old woman?

CULTURED: Accomplished and introspective!

Mann: It’s one of those double-edged swords. You only get to be accomplished and successful at the end of your career. So you spend your whole life desperate for this moment, and then it’s vanishingly short. Once you’re there, all you have left to do is die, really. Just statistically—I’m in the peak of health. I’m probably in better shape now than I’ve ever been in my life. I feel pretty confident now. I’ve never felt confident in my life, and I still have episodic periods of profound self-doubt, but I’ve gotten there. I don’t wanna say self-satisfied because no one would ever ascribe that to me. At the moment, I’m feeling pretty good about this book and the book as a summarizing of my career.

CULTURED: What do you think the biggest shift in photography has been since you started?

Mann: Well, there’s a whole new paradigm. Of course, it’s digital-related. It’s the Internet. It’s computer-related. Photography has changed radically in my life. When I started there were one or two photography galleries and maybe five known photographers. And now, everybody’s a photographer. You can’t beat ’em off with a stick. They’re everywhere.

I’m not on social media in any form. I don’t do Instagram or Facebook or TikTok or whatever Twitter is now called, but when I do happen upon it or people say, “Look me up,” and I’ll somehow manage to get on Instagram, I find that a lot of the pictures are pretty much the same pictures that Larry Clark was taking 50 years ago. What’s changed is the way that [photos] are being transmitted and brought out into the world. There are hundreds and hundreds of photographers represented by galleries now.

CULTURED: Were you excited when digital came around or were you daunted?

Mann: I was a little daunted. I was behind the curve. But I did it. I’m using a digital camera now [for a] series in a Sally Mannish kind of way. I have no prejudice against digital. I don’t feel like I’ve been minimized by digital work. It’s very enlivening and exciting, and I’m having a blast. I have to say, sorry, but it’s so much easier than the way I used to do it.

CULTURED: There’s a line in the book about having this urge to make a career of shattering norms. Is there an art-world norm you’re interested in shattering?

Mann: I still subscribe to the idea of the purity of the art world. I always think of art as somehow above commercialism. Art and commerce are now inextricably melded, so I’m just adjusting to that. I’ve never done commercial work because of that whole rarefied, Olympian idea of art. I guess the celebrity aspect of the art world has never been exactly my ambition. It’s not something I particularly enjoy. I’ve seen it ’cause I’m with Gagosian, so you can’t miss the art-world celebrities who keep the door open. But I’m just a natural recluse.

CULTURED: Is there something that you think up-and-coming creatives get wrong about what it’s like to be an artist?

Mann: I do think there’s a hazard in instant success, and that happens a lot these days. There’s so many people who had this shockingly fast rise into whatever their field is who then just fizzle out. You never hear from ’em again.

CULTURED: Is it an uncomfortable period, that middle stage of your career where you’re not on the way up but you’re also not doing retrospectives?

Mann: It is uncomfortable ’cause when you’re young, you’re full of hope and ambition and confidence. Then you get to a certain level, let’s just call it a plateau. You just have to grind it out and look for the next little moment of ascendancy where you can move to the next level. If you don’t move to the next level, you’re fucked. At my stage in a career, there’s a risk there too, because if you have a reputation and you’ve done well and you’re successful, people are more likely to forgive mediocre work because you’re famous.

Cy Twombly, he did all that really exciting work. And then there was a plateau. America didn’t cotton [on]to his work. They rejected it. He got really humiliating reviews. People don’t write about it now, but my father saved them, and I have a little folder of terrible reviews of Cy Twombly’s work. Then he has this burst of great work at the very end. He’s breaking new ground. It’s full of energy and exciting. If I can be like Cy when I’m in my ’80s, I’ll feel like I’ve lived my life correctly as an artist should. That’s his story, and I’m trying to follow in his gigantic footsteps.

CULTURED: It’s interesting to think of an artist wanting critique or wanting to be pushed that way by an audience.

Mann: I’m gonna give Larry Gagosian a lot of credit for pushing Cy. I know that that’s not the typical role of a gallerist, but he did. He would ship all the materials down to Cy in Little Chicken Switch, as Cy calls our town [Lexington, Virginia]. He would ship everything he needed to make art, so there was like no excuse. And Cy picked up his brushes and went to work.

in your life?

in your life?