What does modern-day masculinity look like when it’s stripped of its polish, but not its power? This question has fueled a new series of monumental canvases from Alex Foxton that confront the trappings of manhood head-on. The paintings make up the artist’s latest exhibition, “Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance,” which will take over New York’s Salon 94 in partnership with Galerie Derouillon.

Trained in fashion design at Central Saint Martins, Foxton cut his teeth at Louis Vuitton, Bottega Veneta, Maison Margiela, and Dior—where former Dior Homme creative director Kim Jones brought him on as one of his first hires. Now, his practice moves between the stylistic prose that grounded his cloth-bound creative output and the painterly cues that educate his on-canvas storytelling. “What I love about Alex’s work is that it has its point of view, and like all great artists, he revisits and refines his work throughout his career,” Jones, who also collects Foxton’s work, tells CULTURED. “He can paint on so many different scales with different materials, and they are amazing to live with. I feel lucky to own them.”

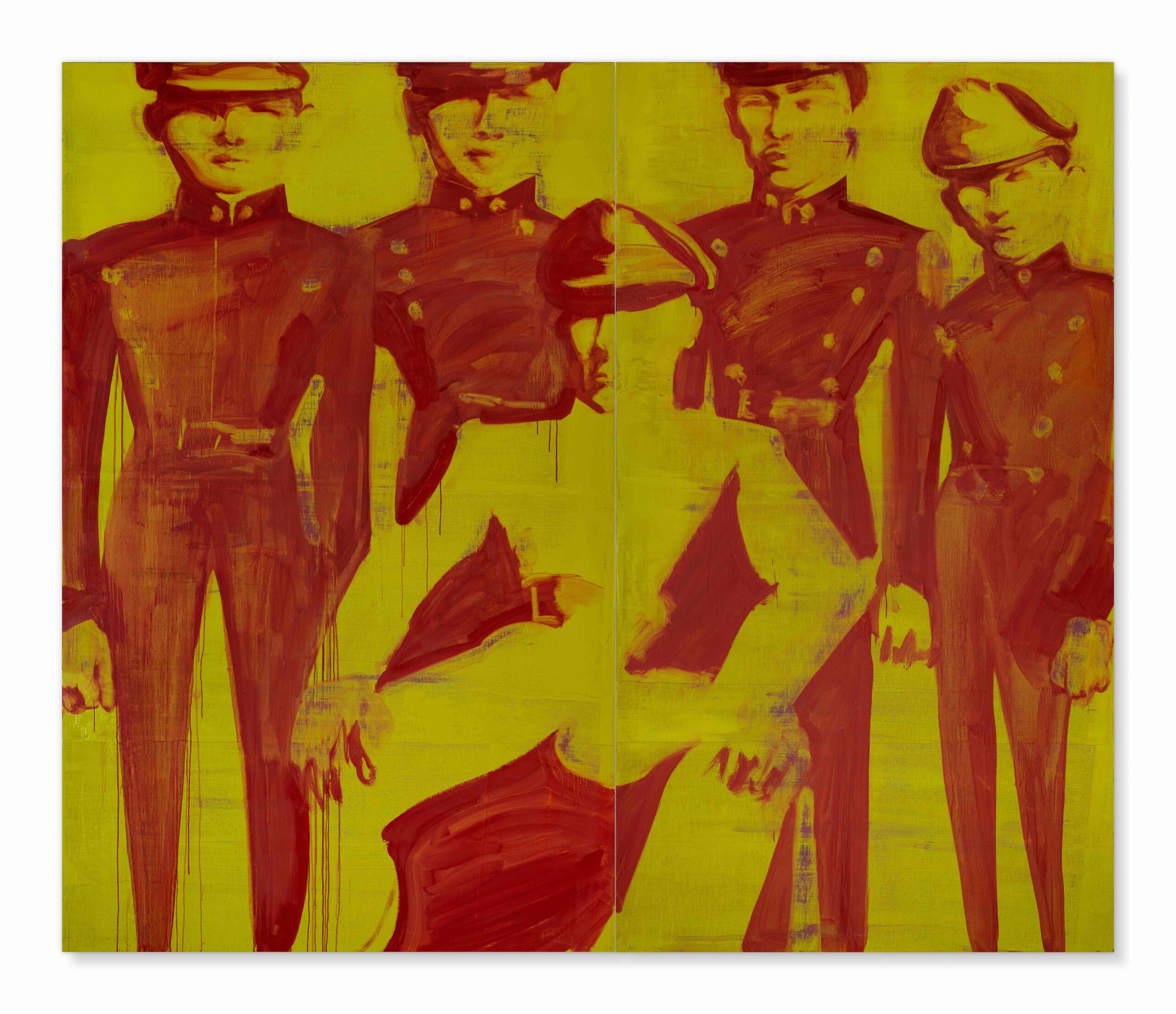

Foxton’s latest series balances desire and discipline, seduction and confrontation, revealing how fragile the idea of the “strong male figure” truly is. Inspired in part by the rawness of today’s theaters of power, the artist takes cues from moments like Volodymyr Zelensky’s unscripted suitless visit to Trump’s White House, the men of the British royal family, fascist armies, and prep school students, laying bare how posture, clothing, and cultural image underscore our understanding of authority. Ahead of the show’s opening on Sept. 10, Foxton let CULTURED in on the process of putting together his most referential works yet.

CULTURED: Your new body of work confronts masculinity at a particularly turbulent moment for gender politics. What drew you to this tension?

Alex Foxton: I remember watching Zelensky’s visit to the White House, when Trump and Vance criticized him for not wearing a suit, and thinking, I should paint that. It was a scene that brought up a lot of what I’m interested in—masculinity, the male body, aggression, virility, image—and put it into focus in a new way. I didn’t end up painting the actual scene, but it galvanized me to focus on what is essential to my work. It made me want to paint in a new way, more directly, with less romance or tenderness.

CULTURED: You’ve mentioned working with a limited color palette that mirrors Western male dress codes, particularly military and 19th-century male dress norms.

Foxton: When I started this series, I couldn’t even look at color and the first studies were all in black and white. I got into Franz Kline and those huge, gestural structures and wondered if I could apply that to figuration. That seemed to relate to Beau Brummell and that idea of purity of image. From there, I started applying military khakis and greens over bright colors, always playing with quite aggressive contrasts. I also had a postcard of Van Gogh’s sunflowers from the National Gallery on the wall which informed a lot of the color. There are few better examples of how to use a limited palette to say something complex.

CULTURED: From author Yukio Mishima to the bullfighter Manolete, Donald Trump to British royalty, your references span wildly different eras and geographies. How do you choose the figures you engage with, and what unites them for you?

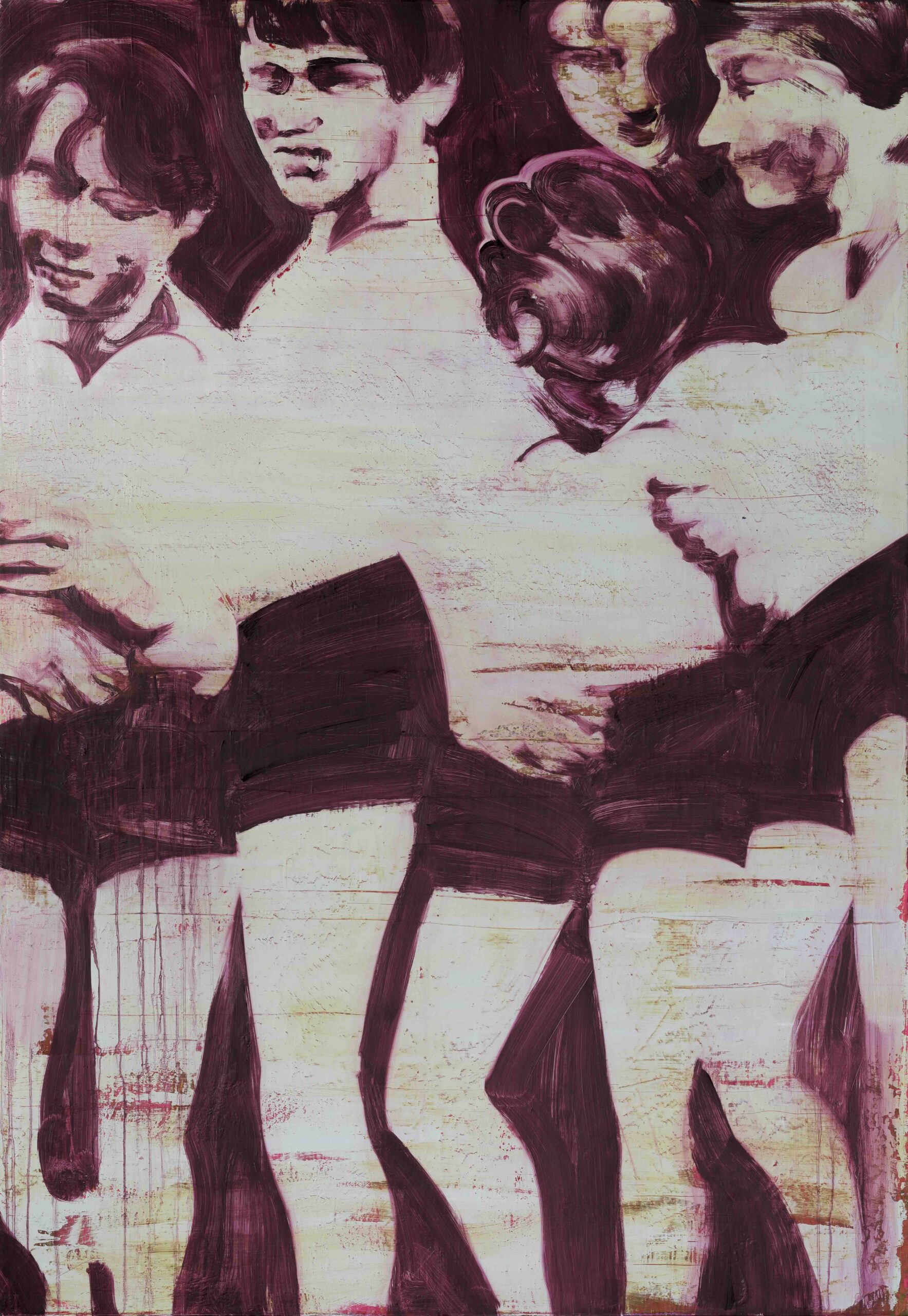

Foxton: I like to say that I paint the images that come to me. Of course that’s only partly true because I’m always looking for them. But only some of them stick around and they usually have a significance that I’m not aware of when I start working on them. For example, I’ve painted Manolete in the past but it was more about his body and the uniform; then I watched a film about him and realized that what fascinated me was his face. His nickname was “knight of the sorrowful countenance,” stolen from Don Quixote. That came out in the process of painting. It’s the loneliness of being a male archetype: you’ll never live up to your own image.

CULTURED: In fashion, especially in the luxury sphere, portrayals of masculinity are designed to project control, seduction, and aspiration. How did your background in menswear shape your approach to depicting bodies on canvas?

Foxton: In a literal way, my background means I know how to draw a body with speed and economy. You could say I’m just doing what I’m good at. But, I also find that the things you’re good at are the things that you’re interested in. So I guess the career in fashion itself came out of an interest in the performance of masculinity.

CULTURED: You’ve spoken about wanting to dismantle the “objective and dominant gaze.” Can you share how you balance critique with notions of desire in your male figures?

Foxton: The desire is part of the critique. To paint a fascist or a politician with a level of desire is exciting to me and seems true. Power and violence are attractive. Spectacle is attractive. It’s dangerous to ignore that. It’s why I decided to make huge paintings this time, because I wanted the figures to be overwhelming, like groups of men often are in real life.

CULTURED: Many of the bodies you paint are torn between emotional states: serenity and strain, ecstasy and torment. How do you navigate that tension in the studio?

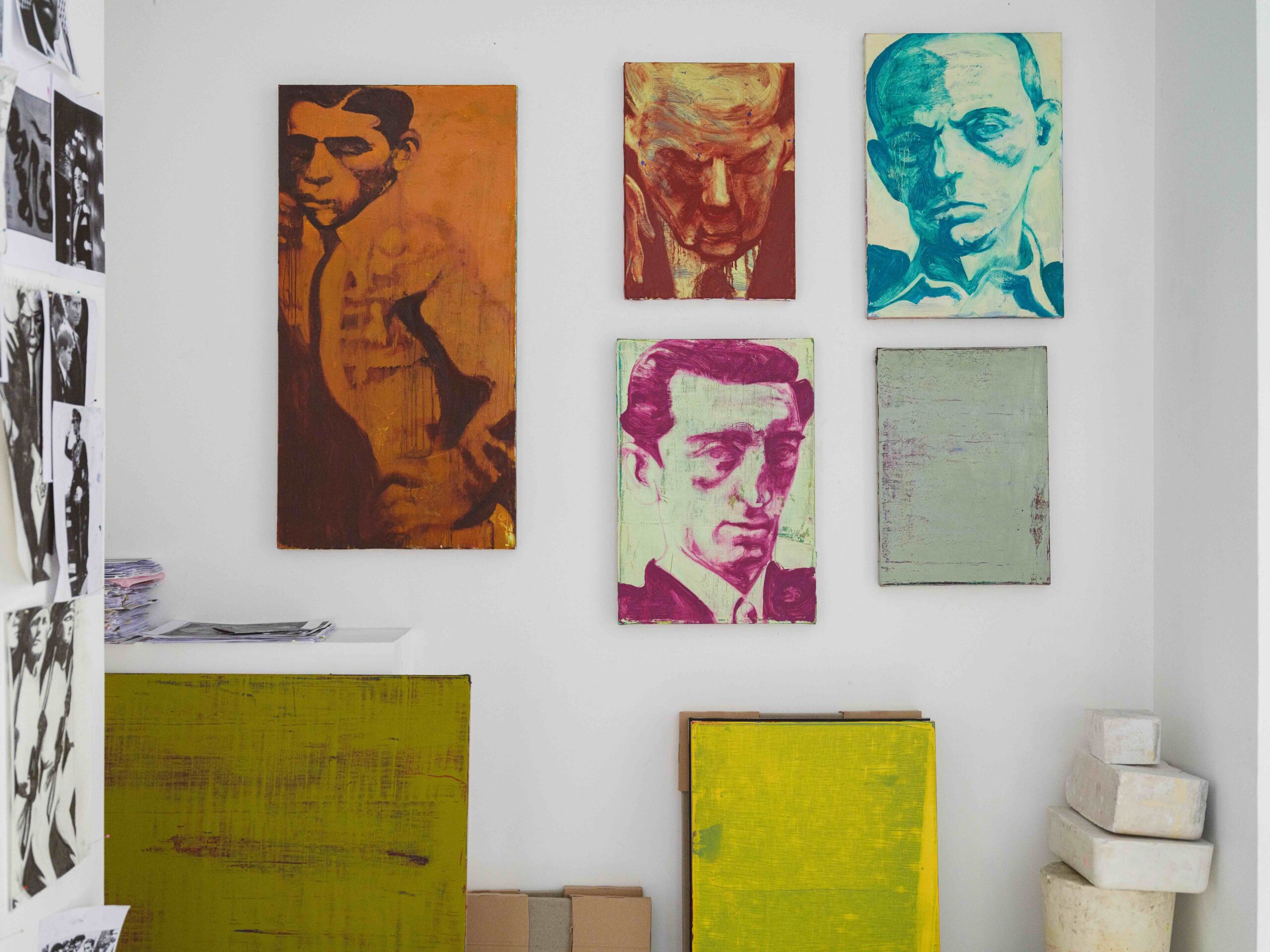

Foxton: That’s a question I think about a lot, because it’s not at all obvious how it happens. A lot of the time ,it goes too far one way and it’s not clear why. If I’m working from an old photograph, I usually know from the beginning that I can get something new out of it, but it won’t become clear what it is until I make a lot of drawings. Often, it’s not there at all until I get to the end of the painting.

CULTURED: Kim Jones describes your work as “amazing to live with.” Do you think about the “after life” of your paintings, or how they occupy space once they leave the studio and gallery setting?

Foxton: I love to see where my work ends up, and I often ask collectors to send me photos of where they put the work. It’s a real pleasure going to Kim’s house and seeing my paintings in those amazing surroundings. It’s like visiting old versions of myself. I also find it almost essential to know the space I’m going to be presenting work in. But thinking about any of that while painting is death to the work. I have to get into a kind of Zen trance where all I’m thinking about is the image and the action of painting it.

in your life?

in your life?