“Music performance is human beings interacting in real time, listening to one another, making collective decisions,” says composer Max Richter. Trying to capture live music in a streamable song is, as he notes, “like trying to catch lightning in a bottle.” For a classical musician, it’s perhaps even more akin to harnessing 100 coordinated strikes—every perfectly timed string, breath, bellow. Richter pulled it off though, with 2015’s Sleep, the first classical record to reach 1 billion streams. Ten years later, the 18th-century form he favors has only become more rooted in the digital age.

When I speak to the 59-year-old, German-born musician in early August, he’s sitting in his Oxfordshire studio before a wall of synths, retro tech, and what must be hundreds of books. Richter’s omnivorous appetite for inspiration and penchant for synthesizers made him an outlier during his composition studies at the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Academy of Music, where there was a clear supremacy of tradition. It also left him uniquely well-positioned for a sea change in the genre. His 2002 solo debut, Memoryhouse, featured John Cage’s distinctive voice, sonic critiques of the Kosovo Conflict, and, as Pitchfork wrote, “Richter’s ability to weave subtle electronics against the grand BBC Philharmonic Orchestra helped suggest new possibilities.”

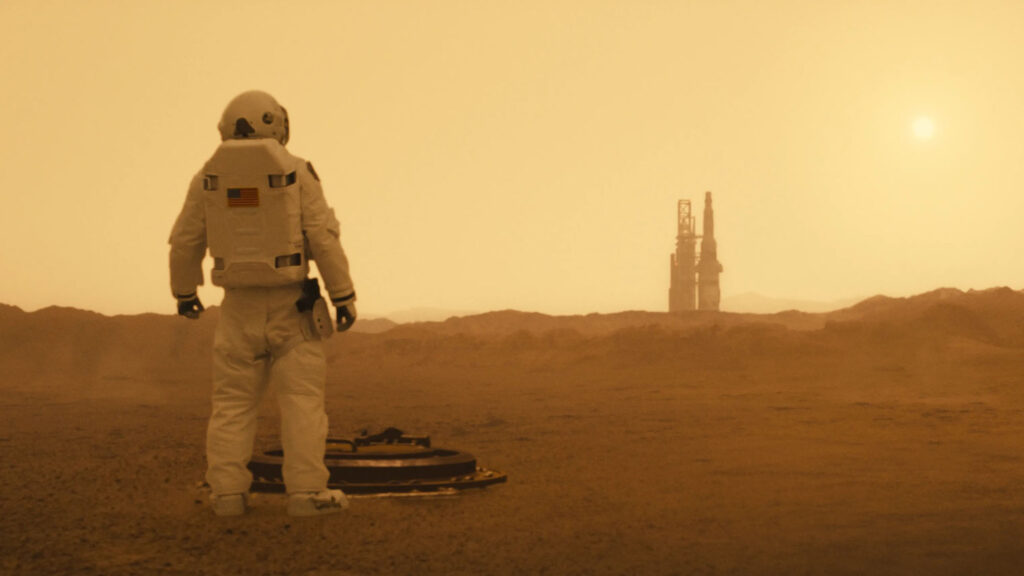

His follow up, 2004’s The Blue Notebooks, featured the lilting “On the Nature of Daylight,” now an instantly recognizable track due in large part to features in Arrival, Shutter Island, The Last of Us, and more. Alongside a steady stream of album releases, Richter has also since composed work for projects including The Leftovers, Black Mirror, and Ad Astra, for which he received a Grammy nomination. “I had no ambition to write film music,” he explains, but the phone started ringing as his songs filtered onto the screen. The line between classical and film composing is widely debated and typically upheld, and yet, Richter speaks fondly of scoring’s influence on the medium and its ability to pull in new listeners.

“You can go nuts in a film score—in ways that would empty a concert hall in five seconds,” he laughs. These flourishes prick the ears of audiences, including those otherwise unfamiliar with orchestral compositions. Some of today’s most well-known composers extended themselves into the mainstream via contributions to the silver screen. Hans Zimmer has racked up hundreds of millions of streams for his work with Christopher Nolan, and among Philip Glass’s most-frequented tracks are pieces he devised for The Truman Show. Richter’s own family cat and dog are named after characters from Hayao Miyazaki movies, famously scored by Joe Hisaishi. (“That music gets played in our house a lot,” says Richter with a smile.)

“Particularly the classic scores of the ’70s and ’80s, John Williams and others, that language goes straight back to Korngold and Mahler,” he expounds. “It’s still evolving, finding audiences and new connections without people even realizing they’re listening to classical.” When asked whether film is in part responsible for financing new classical works, Richter nods along. “I’m sure that’s right,” he says. “Look at Hildur Guðnadóttir’s work or Jóhann Jóhannsson’s.”

But the innovation Richter regularly credits with an uptick in classical fans is the advent of streaming services. “Streaming is borderless—it’s just another click,” he says, recalling a time when listeners would have to walk into a physical record shop, pre-segmented into rock, hip hop, classical, and more sections. Exploring outside your preferred rack meant spending hard-earned money on a new LP. Now, “you hear something, you click, you decide yes or no, and move on. [Streaming] allows people to pursue their enthusiasms without financial risk.” This shift has paid off for classical in particular, which at the time of Sleep’s release, counted only a tenth of its listeners as under the age of 30. That same year, streaming officially overtook all other formats as the primary revenue stream for the U.S. music industry, and five years on, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra reported that 18-25s had leapt to a third of classical fans, ensuring another generation’s worth of demand for the genre.

Ironically, Richter’s biggest project to date, Sleep, was born from a desire to disconnect. At the turn of the 2010s, the composer was spending a portion of his time playing shows around the world. Meanwhile, his partner, artist Yulia Mahr, stayed home with their young children, and in the middle of the night, she tuned into livestreams of his concerts as she faded in and out of wakefulness. “Somewhere else on the planet, she’d be listening in,” he recalls. “She [would tell me] that there’s something special on an emotional level about listening to music in that state. You can’t censor anything.”

During those years, Richter recalls the mounting pressure of a nonstop, digitally connected world. Instagram had just hit the app store. 4G technology had just been installed on phones. “Now we think of that as normal, but it was actually a big deal,” Richter says. “[Yulia and I] were talking about the idea of a piece of music that could function like a pause, like a mini holiday from that.” Sleep was pressed into an eight-and-a-half-hour, 204-track record—as much an experiment in sound as it is a seminal addition to the canon. The project was performed in its entirety overnight at venues like the Sydney Opera House and the Great Wall of China, where Richter remembers stepping offstage to find the armed guards asleep, cradling their guns. “I was like, ‘My work here is done,’” he laughs. But, “it’s not like I’m a Luddite,” he clarifies. “I mean, look at my studio: It looks like NASA ground control.”

On Sept. 5, for the project’s 10th anniversary, Richter is releasing Sleep Circle, a 90-minute continuation of his hypnagogic preoccupations timed to the duration of a REM cycle. He’s also reprising his overnight performances at London’s Alexandra Palace on Sept. 5 and 6. “You can go to sleep, you can stay up, you can do your yoga, you can do your journaling, you can do whatever you want to do,” he says. “You’ve got hundreds of people who’ve basically trusted a bunch of strangers to just go to sleep and spend the night together in a space, which is its own kind of magic.”

Since 2015, Richter observes that the world has only moved in one direction: “Faster.” More than ever, an audience’s need for this kind of artistic reprieve is clear, and creatives are more equipped than ever to produce them. “There’s a democratic toolkit in a way,” explains Richter. “Everyone has the same laptop, and you can make a record straight out of the box. That transparency of tools means there’s this interpenetration of languages.” The composer points to hip hop’s history of sampling—both from audio tracks and genre styles—and musicians like Frank Ocean or Mitski. (“I love Mitski,” he beams.)

Like hip hop, or pop, or any other genre, classical isn’t the same as it was a decade prior. Though it’s often regarded as adhering to a traditionalism far beyond its counterparts, its most successful practitioners are enjoying the porousness and democratization new advancements have brought to the industry. The next generation, though just as likely as their elders to join the droves heading to Richter’s next live performance, are increasingly favoring classical outside the concert hall. It has become the soundtrack to morning commutes on the train, remote work in a coffee shop, cooking dinner with roommates, and TikTok videos. It has interpolated synthesizers, film actors fighting dragons, and protest movements. Most importantly, it’s been compressed to just a few megabytes alongside any other song on listeners’ phones. “I’ve always felt the most interesting stuff happens at the borders of languages and cultures,” adds Richter, “where things rub against one another and create strange multiplying effects. The space now is wide open.”

in your life?

in your life?