In an age when we can wash our hands with Jean-Claude Ellena soap and blow bubbles scented by Francis Kurkdjian, fine fragrance can be found everywhere. But with over 3,000 new perfumes launching globally each year—and more self-anointed scent experts than ever before (#perfumetok alone has racked up over 7 billion views)—it can be challenging to discern which scents are worth the sniff. To help, CULTURED has enlisted three top fragrance critics, each of whom have earned their loyal audience outside of the algorithm.

For ELLE, The Cut, and Town & Country, New York-based journalist April Long has harvested roses in Turkey and frankincense in Oman, winning 15 Fragrance Foundation edit awards along the way, more than any other writer in the award’s history. Always questioning yet eternally optimistic, bicoastal beauty philosopher Arabelle Sicardi treats perfume as both cultural artifact and personal talisman, exploring our collective, complicated relationship with aesthetics. In Los Angeles, CULTURED contributor Maxwell Williams works both as a journalist and as a perfumer/olfactory artist, a rare blend that gives them deep insight into both the science and culture of fragrance. Here, the three tackle everything from the power of niche perfumery, dupe culture, A.I. noses, and the question at the heart of it all: When is a perfume a work of art, and when is it just another thing to smell?

Let’s begin at the beginning. What led you to write about perfume?

Maxwell Williams: I came into writing about fragrance through trying to get away from writing. About 10 years ago, I took a class at the Institute for Art and Olfaction. At first, I was really just dabbling. Then I built a lab in the second bedroom of my apartment, and now I’m a working perfumer. Today, I think of myself more as a perfumer who happens to write, than a writer who writes about perfume.

April Long: Well, Emily, I always credit you with making me the fragrance writer that I became. When you assigned my first fragrance story at ELLE, you said, “I think you will be a good fragrance writer because you are a music writer.” I was like, Really, will I? I set about doing it, and I fell in love with it. I mean, there are countless similarities between the two arts. I went from thinking of fragrance as something not particularly necessary—maybe even obnoxious—to being something that I loved more than any other thing that I could find to write about. Today, I write a perfume column, Good Scents, for The Cut as well as The Pomander, a Substack about fragrance history and the origins of natural ingredients.

Arabelle Sicardi: I’ve been online for far too long, and I’ve been writing about beauty since my brain was literally forming. I started writing about beauty for Rookie when I was still in high school and college, and I think my fragrance obsession was always part of it. It’s core to who I am. The origin story for House of Beauty, my nonfiction book coming out this fall, was my obsession with Chanel No.5 [Perfumer: Ernest Beaux], specifically. Before the book was sold, I spent two years of my life shaping my entire existence around it—traveling the world to research it, going to Berlin and Paris to find materials and evidence about Coco Chanel firsthand.

And you’ve gone from writing about beauty culture to building beauty culture.

Sicardi: I impulsively started Perfumed Pages, which is this scent-centered events collective. I love participating in scent culture, and I wanted to do a collective experiment that was about centering the joy and fun and curiosity and play about fragrance—and beauty in general—because there’s not enough opportunity just for this. It’s really about having a chance to be alongside other people who just really love this thing, and you’re rooting for each other. That’s where I want to be in beauty.

Over the past 25 years, the perfume industry has experienced the same changing of the guard as traditional print media. Nimble, digitally-savvy newcomers have chipped away at the centuries-long dominance of the luxury houses. How has the proliferation of niche perfumery and niche journalism changed how you approach your work?

Long: I came into it right at the moment that things were pivoting to niche. There was a bunch of garbage, the ubiquitous celebrity scents, but then you had Frederic Malle enter the conversation. The biggest change for me has happened in the last five years. Post-pandemic, there’s been a massive shift in the scope of the job, because there’s just so many new fragrances. Fragrance became a touch point for so many people during the pandemic. People were stuck at home worrying about their sense of smell and, then, learned to love fragrance. It became a wellness product and obviously, wellness sells. So now everybody’s got a fragrance, even Hellman’s mayonnaise. I looked up the stat, and 10 years ago, the norm was for something like 400 new fragrance launches a year. Today, it’s over 3,000. You can’t really smell it all.

So how do you smell it all?

Williams: I have a bit of a different perspective on the glut. There are so many different musicians and bands producing so much music—way more than 3,000 music releases, right? And we don’t think of that as a glut. Rather, we should focus on the niches that we are attracted to. So if you find the kind of perfume that you like, then seek out more in that category. This might feel like a little less of a task than having to smell all the perfumes. Because I’m never going to be able to listen to all the albums that come out this year.

Maxwell, I like your advice. However, April, as a fragrance critic who writes for massive publications, your job is to cover the entire industry for millions of readers. Are you expected to test all 3,000 launches?

Long: It’s a beautiful thing that the conversation is so robust. There are Reddit threads, Instagram accounts—what used to be isolated is now everywhere. There are infinite opinions, and that’s amazing. But yes, to be a responsible fragrance journalist for a large readership, you still have to smell all 3,000 of those new launches.

Sicardi: Just thinking about that 3,000 makes my nose run. I am of two minds on this, and I can’t really decide if I need to land anywhere. On one hand, I love how accessible fragrance creation has become. There are more and more niche perfumers that did not and could not exist before, because they didn’t have access to the formal education of going to Grasse, going to the Hogwarts of fragrance. Now you can take educational courses and get formal accreditation through so many more places than even just five years ago. So this has made everything so much more interesting. But we also have more dupe culture than ever before. There’s still this pressure to consume. There’s pressure to have a fragrance wardrobe. Finding a way to balance these multiple natures is part of our task as humans. You have to ask yourself, What do you want out of beauty? Because you can have anything you want if you’re conscious of it, and you determine where you stand. Some people will be absolutely inundated and overwhelmed. Other people really relish the infinite opportunity. And for me, I choose to love the overwhelm.

Let’s talk dupe culture. At a recent CULTURED event for Valentino Beauty perfumer Fabrice Pellegrin, I was reminiscing with a fellow Gen X perfume-head about Primo, “If you like Giorgio, you’ll love Primo!” (one of the original dupes). We grew up hearing about perfumes like Giorgio Beverly Hills [Perfumer: Bob Aliano] in movies and on TV, but for both of us, the nearest Giorgio Beverly Hills fragrance counter was a few states away. At our local drugstore, we had Primo. I desperately wanted to see how it compared to the real thing. The first thing I did when I went to my first big city was track down a Giorgio counter. So although I hate dupes, I have a dupe to thank for my lifelong love of perfumery.

Sicardi: I have such strong feelings about dupes that I wrote an essay about it on my Substack called “Dupe Culture in Beauty is Ruining Everything.“ And by dupe, I mean the ones that are: “This smells like Baccarat Rouge [Perfumer: Francis Kurkdjian].” Yes, dupes make fragrance more accessible. Love that. Ultimately, I would love beauty to be accessible to all people. But not by sacrificing the work of people involved in artistic creation. Your desire for a beauty product does not make you entitled to it. A lot of people assume that because they want something, they should have it—that the people involved in the labor and the resources required to create it are less important than their desire to consume something. I think this is fundamentally a very American entitlement, and one I don’t agree with. Dupes just basically crib someone else’s homework. They don’t further the fragrance industry.

“Ultimately, I would love beauty to be accessible to all people. But not by sacrificing the work of people involved in artistic creation.”—Arabelle Sicardi

Williams: There’s no copyright in perfume. You can’t copyright the juice. It’s a really difficult legal question that gets asked a lot in the arts. [Elaine] Sturtevant claimed appropriation, but Richard Prince was successfully sued, right? There’s Sherrie Levine. It goes back and forth in art. It often comes up in French courts with perfume, but with every case, it’s determined that a scent can’t be copyrighted. The bottle can, but not the scent. Pia Long from the British Society of Perfumers says that the duping trade isn’t just plagiarism, it’s fraud. They are deceiving consumers about the quality and the safety of the perfume, so they are criminals. They might work out of perfumery labs, but they are crooks in lab coats. They’re making an exact replica of a Picasso, saying, “You can hang this on your wall and say it’s a Picasso, and we’ll charge you just half of the price of a real Picasso.”

When it comes to perfume, people often celebrate the dupes they’ve “discovered.” They’re proud to hang a forgery up on their wall.

Williams: Perfume is expensive, and these dupes are cheaper alternatives. They want that fake Picasso. But I’m not trying to be elitist about this. I do think that we should hold space for people who don’t have a lot of money to spend on perfumes. The perfumers behind SAMAR [Na-Moya Lawrence and Debbie Lin], this amazing, small artisan brand in LA, have been thinking of ways to bring people in, to make perfume not such an overwhelmingly expensive thing, so they’ve started offering smaller bottles for purchase.

Sicardi: Throughout history, perfume has always been classist. It was made for royals. All the original perfumers, they were nepo babies. They had royal decrees to be doing perfume art for actual royals. It was a way to create distinction between them and the peons. So of course I’m glad that perfume is more accessible now, and that it doesn’t fundamentally mean that you’re better than anyone else. With a lot of the newer generation of perfume houses, such as SAMAR—it’s not a coincidence that SAMAR is owned by people of color and they’re queer—their understanding of community and politics and beauty are so intertwined. They want to be transparent, they want access, and they want all of the things that are not often afforded to people of color or to queer people, especially in the beauty space. So what they’re doing is very different, because of the people that they are.

When we think about dupes and access, I wish that more people had a better understanding of how hard it is to create a perfume. For perfume, all of the ingredients take so much time and effort, natural or synthetic. Synthetic ingredients can take 40-plus steps to get right. And for naturals—for something like palo santo, you have to find a dead tree. It has to be a female, dead, palo santo tree. You have to have the license to harvest it. It has to be dead a certain amount of time—at least three years—before you can even harvest it. And that’s just one ingredient in a fragrance.

Long: You can be inspired by Picasso, and make something that might be Picasso-esque, but it should still be a work of art in its own right, not just a copy. The fundamental thing that I would love more people to understand: works of art are precious things. And they shouldn’t be duplicated so casually. I’m all for democratization of fragrance, but it does devalue the original. The original loses something of its luster as it’s photocopied down the line.

Do you think part of the disconnect is that many view perfume as just another everyday consumable, and not as a form of art?

Sicardi: That’s a juicy question. This has so much to do with the Industrial Era, and also the fact that social spaces have been sanitized in terms of fragrance. If something is smelly, people get suspicious. There’s a lot of weight to the terms smell [and] smelly. It’s preferred that people in public don’t really have a smell, and if they do wear a fragrance, there’s a certain level of politeness. They shouldn’t smell too much. That’s why I like the work of Dr. Ally Louks on olfactory ethics. People really respond to her because we are starting to understand that smell culture is so part of culture at-large, and [it’s] also so politicized.

Williams: When the photograph was first invented in the 19th century, it was thought of as this kind of novelty. It took a long time until it was brought into contemporary art spaces. A lot of people credit John Baldessari as the turning point when photography started being considered in the fine arts space. Now that we’re seeing perfume being used in contemporary art with exhibitions that are specifically using scent as a medium, perfume as a fine art is coming more into focus. There are people that are out there, like Maki Ueda and Sissel Tolaas, who are extremely rigorous, contemporary artists using scent. Scent is just part of our palette as artists. There’s even an award at the Institute for Art and Olfaction that’s given out to artists that work with scent in their art.

“Scent is just part of our palette as artists.”—Maxwell Williams

Long: The disconnect throughout history has been that you don’t know the name of the perfumer. It’s an anonymous art. So people don’t immediately connect to the idea that this perfume was made by a human being, and it’s so conflated with commerce. To draw on the parallel to photography: not every fragrance is a work of art. Not every photograph is a work of art. It’s about intent. And it’s about skill.

Williams: Over the past 5 to 10 years, people have started to have an interest in the perfumers behind a scent. You can go on Fragrantica, see a perfumer and a list of all of their perfumes, and I think that’s really cool, because there are a lot of people out there who have ridiculously cool resumes—like [Christophe] Laudamiel made Abercrombie’s Fierce but has also made really artistic perfumes for small houses. And I think Fierce is very artistic in and of itself.

Sicardi: Oh yeah, I love Fierce.

I agree, both on Fierce and the importance of the perfumer. Yet, if you ask an A.I. perfume house, they might say that we don’t need perfumers at all anymore.

Williams: I’m really, really, really distrustful of A.I. in fragrance. In anything. For instance, I do want to call out Osmo. They’re claiming to use A.I. to create new molecular structures. I don’t think that’s good. It’s just an attempt to claim ownership over all the new molecules. Look at how the film industry has approached A.I., where the unions push for protections to get the studios to say, “We’re not going to use A.I. for this or that reason.” Perfumers aren’t unionized. I’m also scared it’s going to kill off artisan perfumery because A.I. can now dupe things even faster. A.I. makes it easier for more people to make a reconstruction of an entire perfume.

Sicardi: I’m part of the A.I. working group for freelancers at the National Writers Union, so I’m inundated with all of the news about how A.I. is taking creative jobs in every single industry, and I regularly get emails from people who have lost their jobs because of A.I. I agree with Maxwell that this is going to fundamentally hurt independent and small perfumers, because the conglomerates have already been using all of the technology possible to privatize and patent specific molecules and accords for a really long time. So this A.I. definitely feels like an intellectual property grab. It promises ease of access, but at the risk of what?

Williams: In the Seth Rogen TV show The Studio, they spend a whole episode worrying about a movie being racist. And, at the end of it, they’re still racist, but they leak that they’ve used A.I. And the show ends with Ice Cube and the whole crowd at Comic-Con chanting “Fuck A.I.!” And I just want to say “Fuck A.I.”

SHOP THEIR PICKS

Below, our panel of fragrance critics speak to the scents that they adore.

April Long

Heretic Flower Porn ($195) by perfumer Douglas Little

“I have been through several bottles of this stuff. It’s like wearing the back room of a flower shop: super-green crushed leaves and snapped stems (geranium, violet leaf and olibanum) mingled with orange blossom and rose.”

Kindred Black The Fall of the Immortal Perfume Oil ($365) by perfumers Alice Kindred Wells and Jennifer Black Francis

“Every Kindred Black essence is so exquisite and special. The bottles are gorgeous magic, and many of the florals are sourced from a genius perfumer/enfleurage expert based in Cherry Valley, New York, where my mom lives. My forever favorite is the seasonal wildflower fragrance that I douse myself with all summer, but The Fall of the Immortal, which is based on 19th century Florida Water, is one I dab on all year like a tonic.”

Editions de Parfums Frederic Malle Heaven Can Wait ($348.50) by perfumer Jean-Claude Ellena

“I wear this Jean-Claude Ellena masterpiece incessantly throughout winter. It smells like a vintage French carnation fragrance, with spicy clove and hazy orris, then soft ambrette and vetiver in the drydown.”

Arabelle Sicardi

ICONOFLY Personne Parfume de l’Odyssée ($210) by perfumer Alexandre Helwani

“This is a cult-favorite for perfume-heads, and for good reason. As a writer of course I am tickled by fragrances inspired by literature, and I have a firm, personal ranking of Odyssey translations. The perfume itself is its own journey through The Odyssey‘s smell landscape and when you smell it, you are plunged into the journey with a splash. The wild laurel, rosemary, roses, shipwreck, hemp, and pear! My first sniff made me gasp. And my second. And, and, and…”

Meo Fuscini Odor 93 ($325) by perfumer Giuseppe Imprezzabile

“If I could have any one single brand’s entire oeuvre, it would be Meo’s. Something about his olfactory sensibility just fits me like the perfect leather jacket, you know what I mean? Odor 93 is my current favorite and it’s a flowery, spicy, green. It opens like fog and you walk into it like you’re chasing your own Persephone into hell. It’s a dark, lush dream, like all my favorite stories are, so no surprise that I love it. Smell while you’re listening to the band it’s inspired by: Current 93.”

Jaeger-LeCoultre The Timeless Stories (not available for sale) by perfumer Nicolas Bonneville

“Jaeger gave me a bottle of this when I was mooning over the movements in their latest watches; I didn’t even know they commissioned fragrance before this, but I guess anything they do, they do marvelously. Violet leaves, orris, and leather in a perfectly balanced composition. I come back to it on my wrists throughout the day and learn it a little differently each time.”

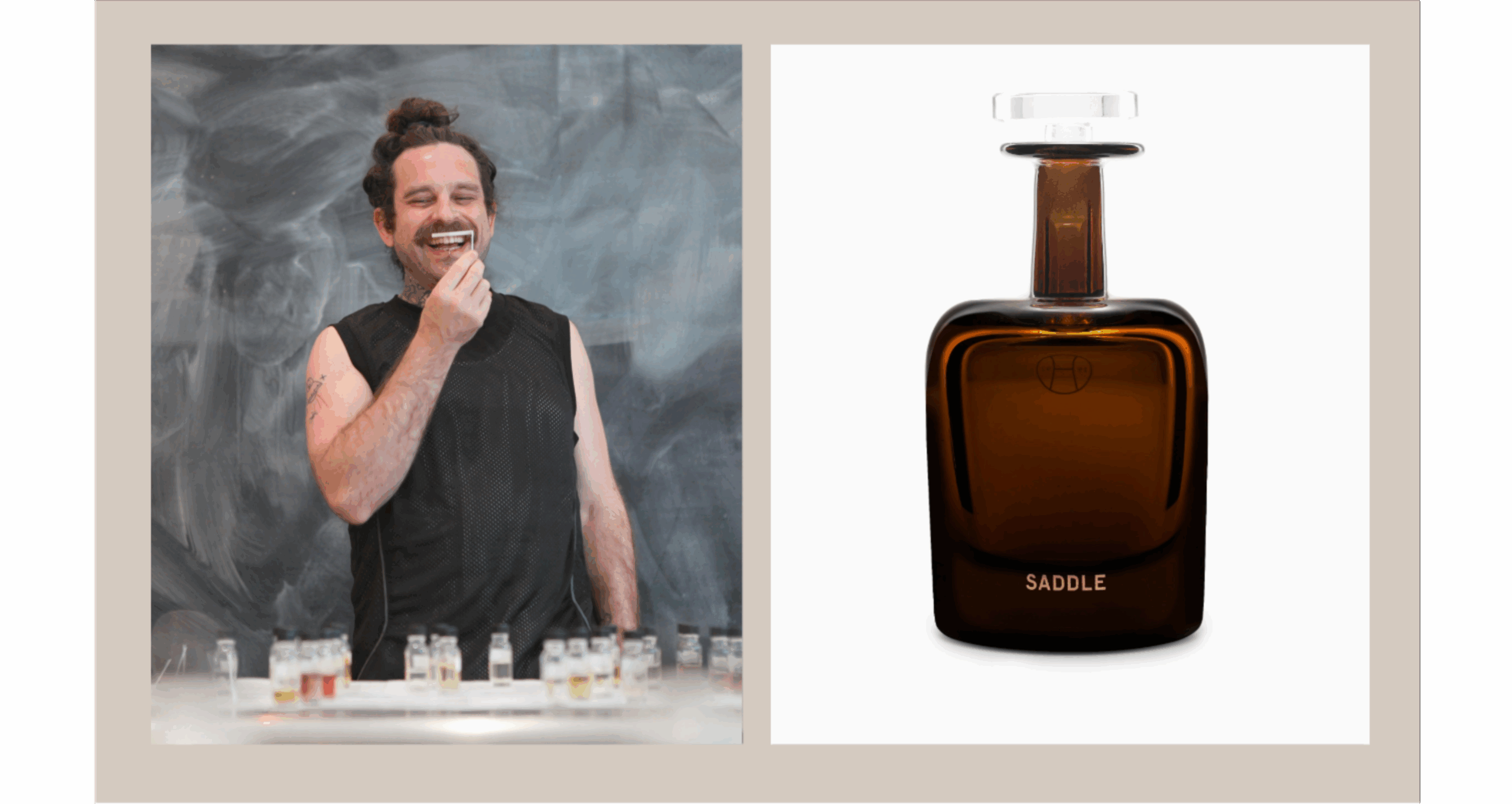

Maxwell Williams

D.grayi Red Jasmine Rice ($100) by perfumer James Nguyen

“James from d.grayi is a mad perfumer. He makes all these tinctures and then builds his perfumes with them. The Jasmine Rice perfume—the red rice version—is so, so good. He gave me a bottle, and my girlfriend ended up buying a bottle of her own. Magical.”

SAMAR Grove is in the Heart ($55) by perfumers Na-Moya Lawrence and Debbie Lin

“SAMAR are so cool. Grove is in the Heart is that long-lasting citrus scent of your dreams. Juicy and jubilant. Funky and fresh.”

Perfumer H Saddle ($205) by perfumer Lyn Harris

“The rumors are true: I’m a horse girl. I love this take on playing horsey so much. The stable, the hay, the leather, the must, the fur, the gallop through the fields—it’s all there. Hermès Galop [Perfumer: Christine Nagel] used to fulfill my horse girl dreams, but Saddle is my new go-to.”

in your life?

in your life?