On the East End, Charlie Marder is known as the “tree whisperer.” The Hamptons-based horticulturalist has collaborated with all manner of notable locals, from Peter Marino and Maya Lin to Julian Schnabel and Helmut Lang, who trust in his reverence for art and its intersection with nature.

Marder and his wife, Kathleen, founded their eponymous Bridgehampton nursery, legendary for its towering redwoods and copper beeches with 30-inch trunks. The New York Times dubbed the place “a horticultural MoMA.”

Across the road from all this botanical grandeur lies Marder’s true passion: rocks. In an open field bisected by a dirt driveway, Marder has assembled a sprawling constellation of geological specimens: 10-ton boulders relocated through feats of machinery (according to local lore, Marder holds the record for the Shelter Island South Ferry’s widest-ever load), pebbled slabs of cliff, stones pocked with primordial patterns.

Salvaged from development sites, quarries, and roadside demolitions, Marder’s sanctuary feels part Jane Goodall sanctuary, part Noguchi sculpture garden: The hulking forms scattered across the field like a herd of sleeping bison.

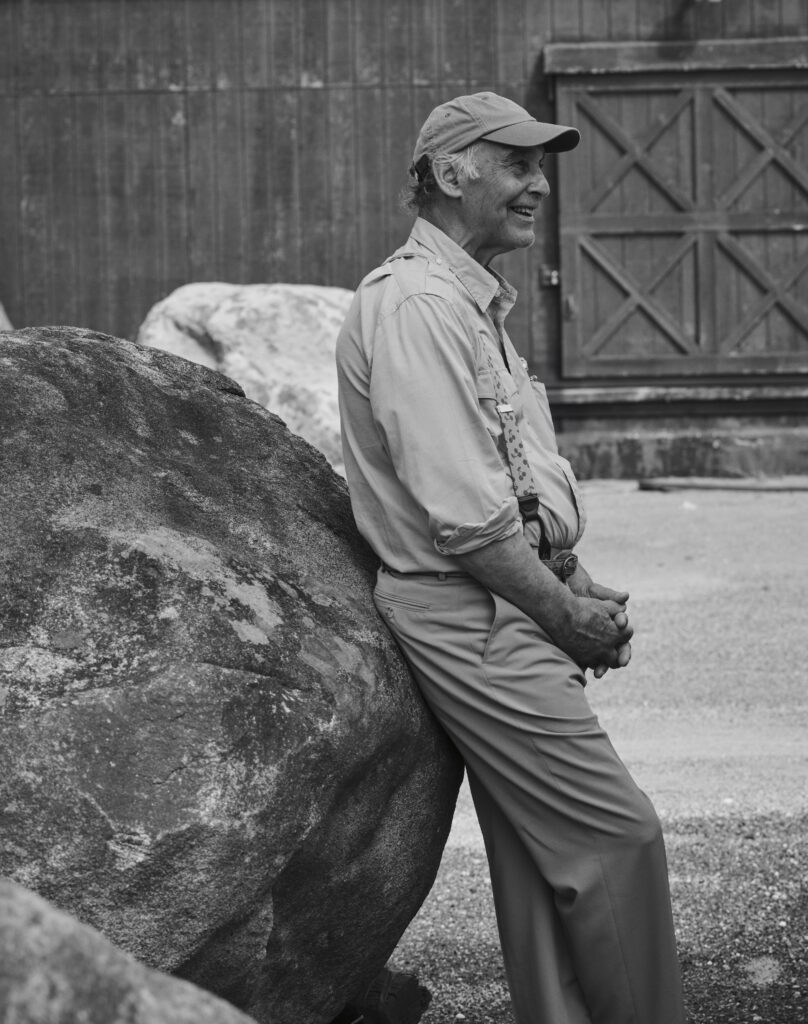

For the Hamptons issue, designer Robin Standefer—who purchased a rock from Marder’s collection for her birthday one year—spoke with the horticulturalist about time on the geological scale, the ethics of placement, and the human urge to give new life to some of the world’s oldest matter—all while perched against a particularly compelling specimen.

Robin Standefer: I came to visit you one rainy day in February, and you said, “I want to show you something.” Suddenly, I was wandering your stone sanctuary, cradled by all this mass and mineral. While the design world chases lightness, [my husband] Stephen and I were getting into heavier objects. I’ve been figuring out how to work with heavier pieces and pure materials: massive stones, solid wood, and bronze. But what you’re doing is on a whole other level.

Charlie Marder: “Heavy” just makes me excited. I’ve always been obsessed with rocks—even before I was obsessed with plants. I remember, as a kid, selling rocks on the side of the road. I gave one to my wife before we got married. It was a nice rock. I found it. Almost everyone has a rock they remember, whether it’s a childhood stone, a marker by the porch, or something that lives in a pocket.

Standefer: I’ve collected rocks for years, but only the ones I could carry. When my birthday came around, I told [my husband] Stephen, “I’m getting older. I want something older than me.” He said, “We should buy one of [Charlie’s] rocks.” When we came to choose one, I spent hours with the boulders. I wasn’t just looking for a rock, I was looking for the one I will live with forever. I was meeting all these different characters. It was as much about compatibility as composition. Striations read like geological and emotional biographies, each revealing a rock’s distinct personality and way of being.

Marder: Some stones might seem smart, others feel lazy. Some are gentle, others are a little edgy. Some like to be alone; some like to be social. They all have something to say. Of course, some are simply rock stars. They make you pay attention. They tell you where and how they want to be—turned just so. They don’t whisper.

Standefer: When I was there with you, looking at the rocks and experiencing their color and stillness, I left with a profoundly heavier heart. What can I say?

Marder: Ten tons heavier. [Laughs] To believe in a rock is to see its potential. When you move them, or shift their context, they reveal themselves. A wild animal in the woods just looks like its generic species. Bring that same animal into a new environment, however, and you start to notice how it reacts and adapts. Rocks do the same thing. Their unique character emerges when they’re placed somewhere new.

Standefer: There’s something primal about collecting and placing rocks. They feel like talismans. Time is the ultimate expression of slow design, and what’s more stable than a billion-year-old stone?

Marder: The tension is that a rock is always evolving depending on where it’s placed: the way the sun hits it, what happens when water collects, when insects move into its cracks. The rock we placed together in Montauk had a slight depression in it. I thought, This is going to form a little dish for water.

Standefer: Sure enough, the birds come.

Marder: Really, though, we’re so unsophisticated about this. The Chinese and Japanese have centuries-old terminology for how water collects on rocks, how moss or lichen grows. Their devotion to nature is so culturally embedded.

Standefer: When you’re constantly moving, you miss the gesture. Most of us only keep the ones that we can pick up, but you’re working on another scale entirely.

Marder: My ability to carry things is exponential, thanks to the crews and machines I have access to. Lifting a giant rock is spiritual.

Standefer: Tell me about what drives your rock rescues.

Marder: I rescue them to protect them. Otherwise, they get buried, smashed, forgotten. Once a rock leaves its resting place, where it’s been since the glaciers, it can’t go back. It needs a new home worthy of it.

Standefer: When did you start collecting rocks, the ones too big to carry?

Marder: Maybe 25 or 30 years ago.

Sandefer: Rock collecting is like discovering an unknown artist, right? Believing in something you think is beautiful and daring to say: “I’m going to invest in this, even though I don’t totally know what’s next.” I know you’ve been Arne Glimcher’s horticultural accomplice for decades. And you’ve also done some work with the artist Lee Ufan.

Marder: I worked with Pace Gallery and the team that helps Lee produce shows, as well as commissions and installations. I brought Lee here, and we spent a couple of days scouting rocks. It’s nice to work with somebody who’s better than you are. Lee sees rocks as partners in composition. Sometimes it takes days to find the right position. Once it’s set, it’s no longer just a rock.

Standefer: It’s about the relationship the object creates between people.

Marder: Exactly. I often place rocks in threes. The negative space between them becomes part of the composition. As you move around them, the perspective shifts, like in a Japanese garden. It’s kinetic, though nothing moves. There’s something ancient about it. I remember one boulder we moved completely shifted how my crew saw the work they do. They treated that rock like architecture. The act of moving it transformed all of us.

Standefer: It’s a kind of reverse obsolescence. In a world obsessed with speed and disposability, rocks are forms of resistance, in a way.

Marder: A rock is like the opposite of a trend. It holds the memory of a place or a time, but is never truly mastered. You can design an entire landscape around it, or you can sit beside it and let it ground you.

in your life?

in your life?