Upon check-in at LGA, I’m told the flight is delayed and I’ll miss my connection in Denver. It’s with that knowledge—that I might be in for a long day on standby for another flight to Aspen—that I select a series (not a movie) from the in-flight entertainment options. The first trailer I watch is a winner: Billy Bob Thornton in a Stetson, pickup trucks traversing desertscapes, oil fields at dusk, football fields at night, catastrophic explosions, and Demi Moore walking, worried, toward the viewer, away from a wall-spanning backdrop that screams “contemporary art.” Landman seems perfect, mostly because the season promises roughly 10 hours of distraction, streamable wherever I end up waiting. I don’t make a thematic connection between the show and my destination—I don’t see it as a kind of psychic primer for my short stay in a very particular, high-altitude microcosm of the art world—until later.

After all, at that point, Saturday morning, just an hour or so in the air, I assumed I’d be missing Matthew Barney’s performance TACTICAL parallax, given my scheduled Wednesday morning departure. (I ended up seeing the dress rehearsal the evening before, riding 30 minutes outside the city to the site—a dusty drill hall-turned-barn—alongside a new friend, the British painter-writer-musician Issy Wood.) And I didn’t know, though I suppose I might have guessed, that Barney planned a meditation on myths of the Wild West, Manifest Destiny, and—of course—football, that would echo the picture of an apocalyptic American frontier captured in the Paramount+ production.

As I settle into Landman’s violent opening scene, showing Thornton’s character Tommy, a fixer for an oil company, negotiating a surface lease in West Texas with a Mexican cartel, a woman on a keto diet, wearing what might be a popsicle-ombre Issey Miyake Pleats Please top, crunches dill chicharrónes and pulls up a spreadsheet beside me.

I land in Aspen five hours later than planned, woozy from the turbulent flight, worried I’ll miss the entire cocktail hour before a seated dinner where I’m expected, but I’m calmed by the astounding beauty of the surrounding mountains and a chainsaw sculpture of a bear holding a welcome sign. Though I’ve come from New York to talk to Issy about her work—in a public conversation for the Anderson Ranch Summer Series on Monday—I find myself stepping into a whirlwind of events I was only partially aware of beforehand. There’s Aspen Art Museum’s AIR festival, helmed by the miraculous Nicola Lees, for which an overwhelming number of talks and performances (including Barney’s) are planned. Two art fairs will open shortly. And the week’s finale (after I leave) will be the museum’s auction and gala, honoring Glenn Ligon.

I’m picked up by the hotel shuttle and learn a little about Aspen from the young driver (“these houses,” he says, tapping the window to gesture at sprawling modernist structures nestled in the slopes, “are empty except for maybe two weeks a year”). I drop my stuff off in Snowmass and take an Uber downtown to the museum. In the stunning, top-floor, panoramic-view restaurant, I chat about San Francisco with a tall guy who I later find out is the VP of human interface design for a major technology company, and then with MoMA’s board president, Sarah Arison, about summers in this Rocky Mountain idyll. When I see Paul Chan and Aria Dean, I realize that the artists participating in the “closed-door retreat”—the glamorous think tank component of AIR— have arrived, and we all find our place cards at the long table. I have the beyond winsome chief curator Daniel Merritt next to me, who gives me an effusive rundown of the Sherrie Levine show below us, and introduces me to Mimi Park, who has been at work all day on an installation (an unfixed floor painting) at the Aspen Center for Physics. Across from me are the artists Martine Syms and P. Staff, who’ve just completed their first day of the retreat. I want a full report, but they only describe, in vague and diplomatic terms, a session of considerable emotional intensity. (There were tears.) P. and I talk—also with considerable intensity—about the setlist and scenography of Lana Del Rey’s recent U.K. and Ireland dates.

TBH, the vegetarian option isn’t great. And I shouldn’t have taken even one sip of wine. Weirdly tipsy and delirious from the thin air and my day’s sustenance of Sour Patch Kids and cashews, I feel far too existential. Maybe you know: During such art-world convenings, in settings of obscene wealth, one observes the familiar but suddenly heightened contradictions on parade; the uneasy symbiosis of supposedly adversarial actors; the unspoken détentes between ill-defined forces; the fleeting funhouse-mirror moments when cultural authority and economic precarity appear to correlate. It’s a world—or rather a constellation of worlds, a field—mapped incisively by the path-lighting practitioner of Institutional Critique Andrea Fraser. But when I first studied her Venn-ish diagram of tipped and translucent, overlapping rectangles—it was published in e-flux last year—I wasn’t quite sure where I fit in. Now, gripped by the same self-centered question, I think, well, I could just ask her. Fraser is just a few seats down from me, deep in conversation with none other than CULTURED’s editor in chief Sarah Harrelson.

Sunday, I don’t leave my hotel room until nightfall. I finish watching Landman, the unconscious poetry of my entertainment choice becoming more clear during episode six, when “the house in Aspen” is enumerated in the context of marital assets surrendered per a violated prenup, and when Tommy—who has just witnessed a worker die, crushed beneath a stack of drill pipe—arrives at his boss’s Fort Worth mansion, home to a remarkable art collection. A Hockney swimming pool, a Bleckner flower, an Avedon cowboy, and much more are dwarfed by the piece that so dramatically frames Moore in the trailer—a portrait of what looks like a battered cyborg-child, rendered in an Adrien Brody-ish mélange of styles by the previously unknown-to-me artist Justin Bower. (I look the ghastly painting up.) As Tommy takes it all in, bemusement, envy, and class rage burn in his tired eyes like an oil rig’s gas flare in the night.

Four episodes later, I reach the cliffhanger finale and turn to my homework, which is to prepare for my talk with Issy tomorrow. Gazing at her paintings, I try to form questions from my scattered ideas—about image production/metabolization in the post-pixelated digital era of style-as-filter; her unusual, slightly drab palette and fuzzed out realism; her girlish accumulation of things via her cagey mode of depiction; her testing of the tchotchke as a fraught subject, its glossy capacity or failure to retain sentiment when captured on canvas (linen, velvet). I listen to her music. And I open the PDF she’s sent me of Queen Baby, a compilation of writing she first published on her blog in 2021 and 2022.

As a diary—with entries appearing in reverse chronological order—it delivers on the form’s dual promises of mundanity and tea, and I find myself quite moved by the work’s forthright characterizations. There’s an open expression of disappointment, disillusionment, and wounding, paired with a certain nothing-to-lose, enfant-terrible insouciance regarding her disappointers. That she does have something to lose (a real career) makes the twin tales of her entanglements and subsequent breaks with famous men—Larry Gagosian (who sought to represent her for two years) and Mark Ronson (who signed her to a major-label imprint during the pandemic)—refreshing and uncommon, even as I’m pulled along by a voice I feel I’ve known forever. We meet for the first time that night, right after she gets in from London, eating downtown together at Ellina’s. I have an incredible bowl of spaghetti.

Monday is a beautiful day. Issy and I talk (privately) for hours at an outdoor table at the ranch, where she’s staying in a cabin. Later, our scheduled (public) talk passes in a blur. She’s cool but not at all aloof, like her writing. At the cocktail reception after, I sit with Cathy Opie for a while, who generously overstates my contribution to a project at Thread Waxing Space in 2000, when she shot a stunning series of large-scale Polaroid portraits of Ron Athey as a queer-BDSM Christ with HIV. (I was the curatorial assistant; I fetched lattes.) Those were the days, we shrug: awful, but not as awful as today. I also talk to writer Evan Calder Williams who, in explaining the concerns of the AIR retreat, which he’s helping to shape, terrifies me with the concept of “personhood credentials” and our impending or ongoing total war with A.I. (not in so many words). At dinner, I sit with the ageless Roselee Goldberg, director of Performa, and press her for details on Canyon, the time-based art exhibition space slated to open on the Lower East Side next year. New acquaintances across the table gossip and roll eyes—without malice—about Tim Blum’s end-of-an-era announcement. Linda Goode Bryant— artist, icon—speaks to a rapt audience on origin stories and imagination, and we clear the air, of everything, when we clink glasses.

The early 20th-century Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi proposed that we’re all desperate to return to the sea. There, our body weight was supported by the water; what needed to be mixed was mixed outside our bounds. Now, having been driven by evolution from the ocean, we must contain our fluids within our bodies—to protect the embryo. Penetration is invented. Birth crashes the infant on the shore, reenacting the primal trauma, the catastrophe of life on land. This electrifying theory, which stays with me all day, is summarized more eloquently than this by author Jamieson Webster during her conversation the next morning with P., who is just as charming and smart on stage as at dinner. Their dreamy conversation about dreaming, dying, and color follows the Tuesday morning screening-performance of filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul and composer Rafiq Bhatia’s exquisite On Blue, 2022, its score played live by the Aspen Contemporary Ensemble beneath the glowing stained glass of the Aspen Chapel.

Later, Issy and I go back to the museum to see the triumphant triple feature of exhibitions, walking first through Solange Pessoa’s incantatory, room-filling geological indexes, then a vest-pocket show of Carol Rama’s works—valiantly perverse antifascist drawing-invectives from the 1930s in lovely art-deco frames as well as a group of her later, AbEx-y black painting-assemblages peppered with doll eyes. “Sherrie Levine: 1977-1988” charts the development of the great artist’s razor-sharp postmodernism, revealing new qualities (lyricism, fearsome craft, a sense of play) that I didn’t completely see before. The show deserves a few thousand words all to itself, really. (Issy texts me when I’m back in New York, telling me that the curator, Scott Portnoy, gave her an amazing tour. I feel terribly left out.)

We go upstairs, to the restaurant level, to see a conversation between Álvaro Enrigue and Adrián Villar Rojas, and after, when I break a plate (my kale salad and croissant sliding backwards on the tilted plastic seat of a chair when I set it down), I decide that’s my cue to leave, squeezing past Hans Ulrich Obrist on my way out. I walk around downtown alone and get ice cream before returning to the museum to wait outside for Issy, who’s gone to her room (she’s moved from the ranch to a hotel downtown). I’m overjoyed to run into Lloyd Wise, former executive editor at Artforum, who shepherded my prose to print for a decade or so (he’s a director at Garth Greenan Gallery now and also married to genius fashion critic Rachel Tashjian). We catch up until we have to go our separate ways. A day or two later, when I tell him I’m writing a diary I wasn’t planning to write, he helpfully messages me beautiful pictures of Jota Mombaça’s performance at the Hallam Lake Nature Preserve that evening, and of the party the next night, after Barney’s performance, where some say Rachel Harrison cut Werner Herzog in line for food.

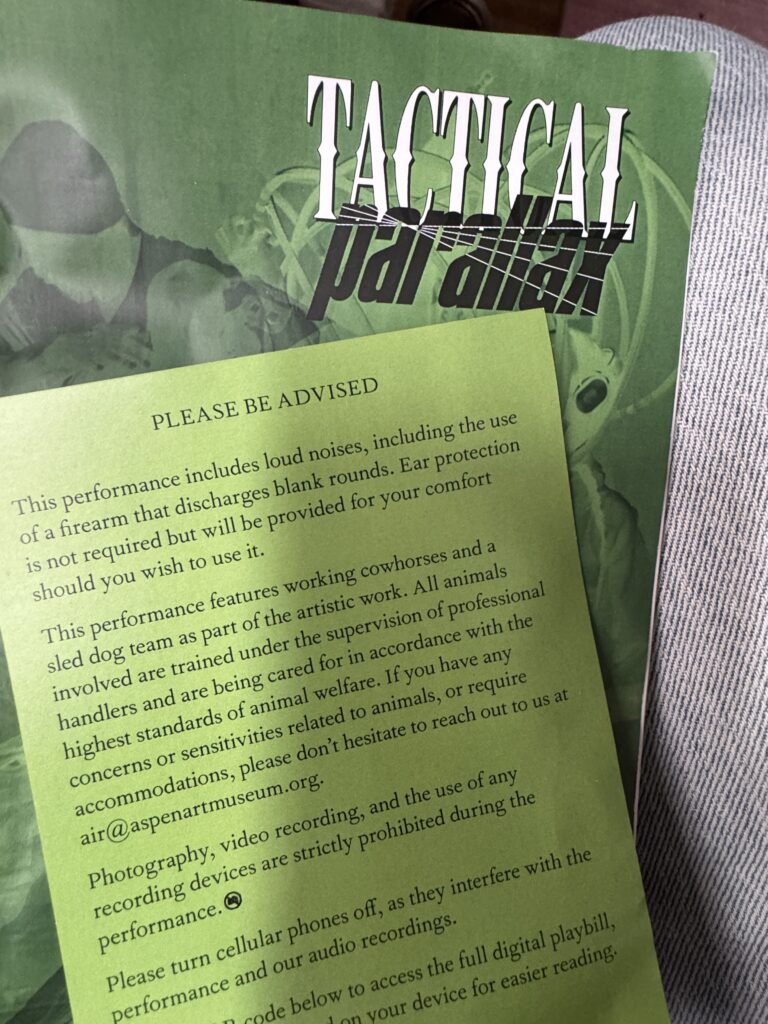

And now I arrive back at the beginning of my story. Issy and I board one of the small, chartered buses, the same one as Jamieson Webster—I’m starstruck—to see the dress rehearsal of TACTICAL parallax, 17 miles away, in the Camp Hale Field House at McCabe Ranch in Old Snowmass. Before our departure, to suspenseful effect, we’re warned the performance will include “the use of a firearm that discharges blank rounds” and informed that the participating sled dog team and cow-horses are being cared for professionally, “according to the highest standards of animal welfare.” No one gets off the bus. We chat and watch the scenery (a fellow passenger points out a “private-jet parking lot”).

The playbill’s detailed text explains that the significance of the work’s site-specificity is not limited to its place on a map or its rural character; the Field House—before it was used for cattle ranching—was a key multipurpose structure within a WWII military training facility, home to the 10th Mountain Division, which trained for alpine, winter warfare. The massive domed wooden building, both hangar- and ship-like, layered with associations, becomes a numinous container for Barney’s precision choreography of competing formal languages—the symbols and movements of ranch work, hoop dancing, cabaret, sports, army drills, and hunting. As it happens, I attended another momentous, ambitiously syncretic, ambiently violent performance in a historic drill hall, early this year—Anne Imhof’s DOOM at the Park Armory in New York—but Barney’s is of another aesthetic universe. The remote location, the stern onboarding of the audience, the building’s yawning entrances with their sweeping mountain vistas, make for something starkly ritualistic even when the performance devolves into excess—if it does.

An attempt at a neutral description of the work, or even a listing of its elements—from the magical entrance of the dog sled to the string ensemble, the standout performance of Okwui Okpokwasili to the ominous presence of a sniper—plays up the potentially sensational and shambolic aspects of the work, belying its structure of slowly shifting triangulations. Talking to Issy on the way back, we agree that performance’s opening scene, in which Barney methodically drew on the dirt-floor expanse with a line-marking machine (for football fields, I think) was a quietly profound gesture that the rest of the piece may have elaborated on beautifully, but never bested.

Following my likely comical understanding of Ferenczi, I wonder if every human-made demarcation is an artifact of trauma repetition; if it represents a return to that moment of exile from the sea, when the body became defined by its borders, a tragic vessel for its own fluids. Expansionism, here or anywhere, with its interminable drawing of lines, thus becomes the catastrophic geopolitical expression of working that shit out. Everyone is a kind of landman, I guess, trying to make and remake their mark. Last week in Aspen, that meant making money or making art.

in your life?

in your life?