Stan Douglas

Hessel Museum of Art | 33 Garden Road, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY

Through November 30, 2025

“Ghostlight” takes its name from a commanding 2024 photograph by Stan Douglas that opens and closes the circular loop of his survey exhibition at the Hessel Museum of Art. In the image, the muted glow of a ghost light—a single, bare bulb—illuminates the empty screen and French Baroque interior of the Los Angeles Theater, a lavish Hollywood movie palace constructed in 1931 and defunct since 1994. Principally used in vacant auditoriums, such lights are also speculated to ward off a room’s lingering spirits. Idle and cloaked in shadow, the proscenium of Douglas’s image underscores a central focus of the exhibition: his concern with the ways we’ve pictured the world in past eras—and thus how we view the present—through images, written history, and mass media.

For more than 30 years, the Vancouver-based artist has mined primary documents, archival photographs, and eyewitness accounts to create meticulously staged historical scenes and imagined scenarios, often indexed to the coordinates of a specific time and place–the 18th-century coastlines of Nootka Island, British Columbia; pre- and post-Cold War Germany as witnessed by a young Black protagonist; or New York in the throes of a fictional 2018 blackout. Spanning still and moving-image work from the 1990s to 2025, and organized by Lauren Cornell, this precise and taut retrospective assembles several bodies of work that collectively posit history as a haunted and unfinished enterprise, latent with deferred and indeterminate possibilities. The show is anchored by a new work: the North American premiere of Douglas’s Birth of a Nation, 2025, a multi-channel video that estranges the fraught racist narratives of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film to tremendous, pensive effect.

The artist’s attention to specific historical episodes allows him to situate broader global and ideological forces within local and particular incidents. “My works … address moments when history could have gone one way or another,” he explains. “We live in the residue of such moments, and for better or worse, their potential is not yet spent.” The most powerful moments in the exhibition come when emphasizing these critical junctures, notably in a room uniting two series: Douglas’s “Crowds and Riots,” 2008, a group of elaborately staged images depicting gatherings of union workers, protestors, and racetrack patrons, and a more recent suite of panoramic photographs, 2011 ≠ 1848, 2017-2021, which uses a similar strategy of recreation. In 2011 ≠ 1848, the artist analogizes the populist uprisings of the title’s two years, representing moments of public unrest in 2011, including Occupy Wall Street protests, the Arab Spring in Tunis, and riots in London and Vancouver. To make these sweeping tableaux, Douglas reviewed hours of aerial news footage, interviews, and social media posts from the original events. The process lends his studied reenactments an uncanny documentary authenticity that attests to these spontaneous mass actions as expressions of revolutionary political will, rather than as the eruptions of an inarticulate mob.

While some of the works here refer to verifiable events, others manifest absent accounts or unrealized histories, often through fictional authors of the artist’s own invention. Midcentury Studio, 2011, produced under the guise of a fabulated postwar photographic press reporter, comprises photos of gamblers, squatters, and crime victims, made by enlisting actors and era-appropriate flash camera equipment. In this and other works, Douglas makes images of unrecorded or impossible scenes that subvert the evidentiary status of the camera for more speculative ends.

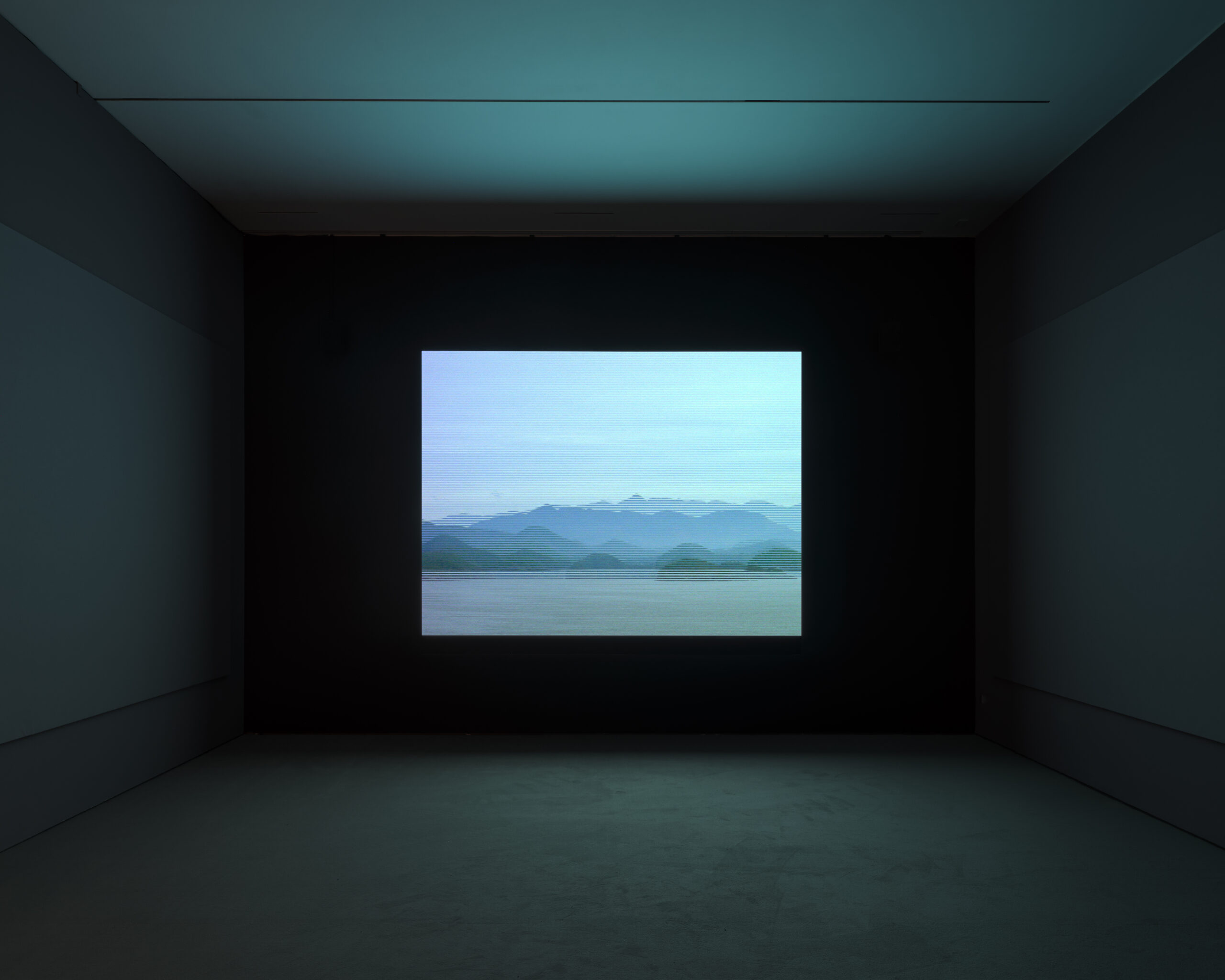

This perspective is evident in Nu•tka•, 1996, a projection that composites two extended shots of Nootka Island in British Columbia, Canada, by weaving the alternating horizontal bands of footage from the two shots into a single video image. An unruly audio track echoes this doubling motif by layering an exchange between two invented 18th-century European sea captains, using overlapping voiceover composed from diaries, Gothic literature, and colonial texts rife with racial fantasies and anti-Indigenous paranoia. In the video, Douglas intentionally omits imagery of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations peoples for which the island is named, highlighting how Western archives tell only a partial story of settler violence. Through this pointed exclusion, the eerie projection—a striated picture of land and sea—mirrors an erasure, and alludes to the violence of landscape painting traditions that depict the “New World” as an uninhabited, idyllic natural sublime.

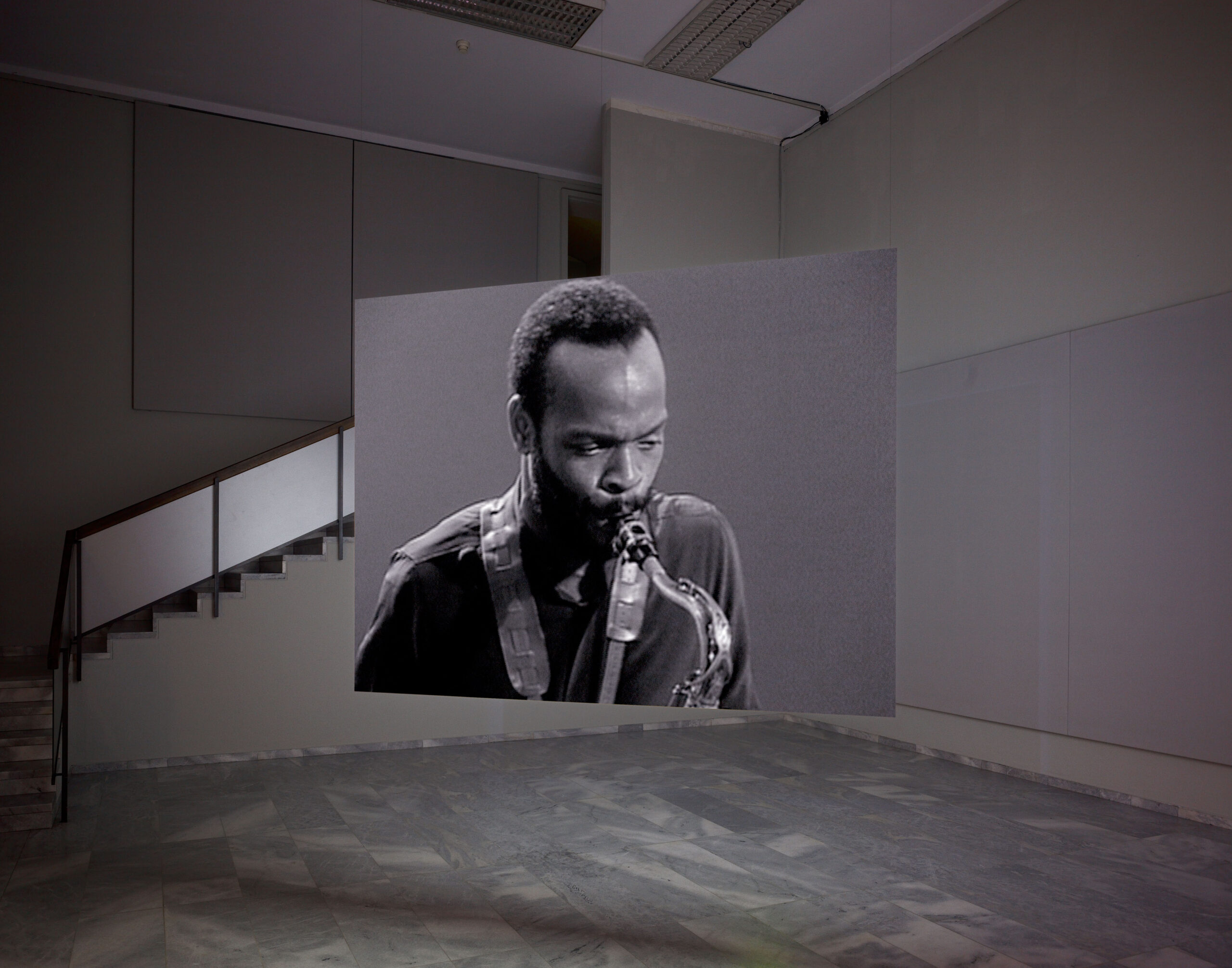

Nu•tka• is one of several moving-image works judiciously paced throughout the exhibition within partial or completely enclosed black box spaces and, at times, adjacent to related series of still photography. One is Disco Angola, 2012, a photo series that connects the Pan-African ambitions of post-independence Angola with 1960s disco culture. The nearby video Luanda-Kinshasa, 2013, tenders an energetic jam session in a studio reminiscent of “The Church,” the legendary Columbia Records sound studio in New York. Matching the funky improvised flourishes of the recording session, the fluid camerawork swerves between a band of jazz-funk musicians selected by pianist and composer Jason Moran.

Douglas’s interest in global lineages of experimental music is further explored through the inclusion of Hors-champs, his 1992 two-channel tribute to the utopian promise of free jazz, which premiered at Documenta IX to international acclaim. In the video, an ensemble of four African American jazz musicians known for having left the United States to work or train in France improvises on “Spirits Rejoice,” a piece by experimental jazz composer Albert Ayler (whose untimely disappearance and death, in 1970, was shrouded in rumor and speculation). The result is a study on presence and absence. One side of the screen shows an edit of the improvised session, while the reverse presents outtakes, troubling the typical division between the smoothly edited recording and the unseen, wayward alternatives often excised from a final work.

Like Douglas’s film and photographs, our accounts of history are constructed, not simply captured. And the tools employed to forge those histories matter. Several works in the exhibition appropriate the photographic and filmic vernaculars of obsolete media formats, while questioning how these outmoded systems authorize truth in our world—crime-scene reportage, citizen photojournalism, verité documentary footage—and Hollywood motion pictures, with their fantastic, unsurpassed ideological potency. This is exemplified by Douglas’s treatment of The Birth of a Nation. In his version, the artist recasts a notorious chase scene from Griffith’s racist, pro-Klan film, showing it from the perspective of two Black characters. Douglas composited new and existing footage, incorporating black-and-white silent film aesthetics consistent with early-20th-century productions. Presented in 2025, a year marked by the chilling resurgence of revisionist right-wing policies aimed at erasing Black histories from textbooks, memorials, and public institutions, Birth of a Nation takes on a heightened salience. As much as Douglas’s work speaks to the past, he considers it “allegorical of the present.”

It’s easy to dismiss the questions posed by this exhibition as purely academic, removed from the politics of real life. But art can be a refuge for reevaluating and assessing history’s crucial turning points, and for recognizing when we ourselves have reached such a point. The success of this exhibition isn’t so much in its deft demonstration of Douglas’s approach to history as a living and unfolding medium, it’s it in its capacity to stop us, and ask that we consider the poetics of history, and the surprising efficacy of music, films, and public actions that might initially appear devoid of clear liberatory potential. In this sense, the ghost-lit theater of the title image, as a site for mythologizing narratives of human experience, serves as a fitting emblem for Douglas’s art. While the stage might appear dormant, its many ghosts wait expectantly in the wings.

in your life?

in your life?