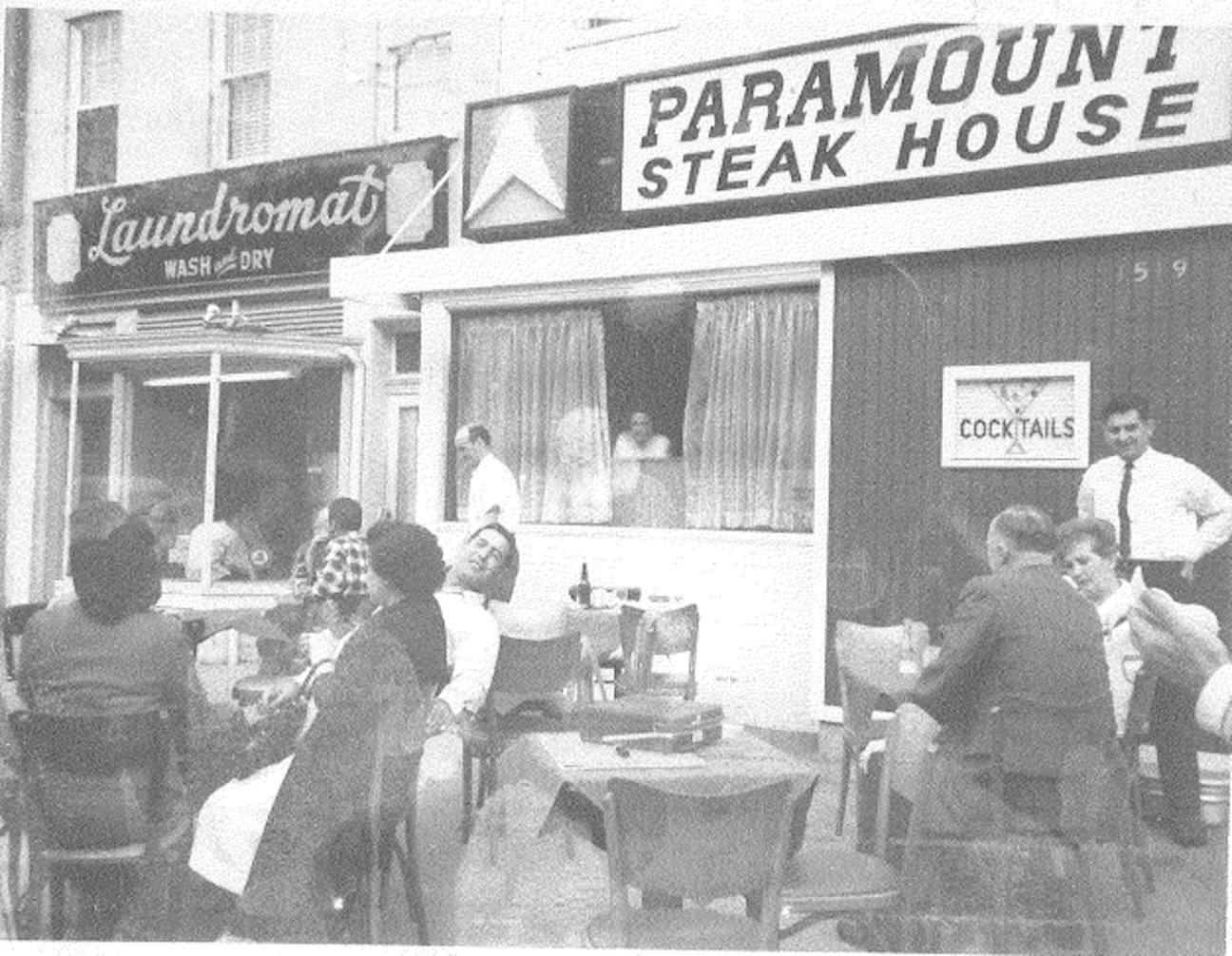

Annie Katinas at Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse in Washington DC. Photography courtesy of the restaurant.

For Gen Xers like me who came out—and of age—in the ’90s, gay restaurants were as ubiquitous as gay bars. In the Nevermind/Clerks/Friends decade, morning through midnight, I could pickup a local gay weekly and choose from dozens of restaurants where my gays and I could eat cheaply and well—without enduring the menacing straight-boy glares we got at TGI Fridays.

To step into any restaurant filled with your people is to feel safety, camaraderie, and tribal joy. Gay restaurants have served that purpose for decades, sometimes surreptitiously: At automats in the 1930s, gay men discovered one another by holding a stare, just a beat or two longer than socially acceptable, while polishing off a burger. Later, of course, they did it openly too—at the scores of Pride flag–fronted restaurants that surfaced in post-Stonewall urban enclaves like the Castro in San Francisco or Manhattan’s West Village.

But today—as mainstream culture steadily feeds off of LGBTQ culture and the Internet makes everything from sex to dumplings easier than ever to access—gay restaurants have started to disappear. I know because I watched it happen. In recent years, my favorite spots shuttered for good.

I’ll never again slide into the chubby avocado-and-russet-striped banquettes at the Melrose, which shuttered in 2017 after 56 years in the Chicago neighborhood Boystown, for a broccoli and cheddar omelet and a cup of tangy sweet-and-sour cabbage soup. And I’ll never get over that.

It’s hard to say how many gay restaurants have closed in the last 20-odd years; the definition of a “gay restaurant” is too slippery. (To me, more than ownership, it’s a matter of mostly gay clientele.) A Los Angeles gay and lesbian business directory from 1982 listed 51 restaurants; a 1978 edition of New York’s Gay & Lesbian Yellow Pages listed around 60. I struggle to imagine a 2025 directory with anywhere near those numbers.

It’s a sign of progress that many LGBTQ people feel comfortable at most restaurants, at least in gay-friendly territory. To eat out without fear or shame—isn’t that what we asked for? Yet with progress comes loss, and nobody feels that more acutely than the Stonewall generation and Gen X gays who, for decades, have gathered (out of necessity as much as want) in exclusively gay restaurants. Baked into this progress is a dilemma: Where do we go when there’s no place for us to gather?

It’s a question I’ve spent the last four years trying to answer. My book Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants, is an attempt to understand where and why queer people have gathered for meals over more than 100 years. When it comes to gay placemaking, I learned, restaurants are just as important as bars. One of the most heartening discoveries I made during my research for the book was that, even as gay neighborhoods have diffused, some gay restaurants—mostly family-owned spots that have been open for decades, with menus that rarely change—have persisted. The reason is simple: It’s not about the food, and never was.

I enjoyed the frisbee-sized, butter-soaked pancakes I ate at the counter at Orphan Andy’s, a gay diner that’s been in the Castro since 1977, that I visited as part of my book research. But what I remember more vividly is the group of five hairy leathermen in the window booth who compared paddling techniques over a shared plate of fries.

One of the legacy restaurants in the aforementioned LA directory was Casita del Campo, opened by Rudy del Campo in 1962 in the Silver Lake neighborhood and still in business today. The del Campo family’s Mexican establishment quickly became a hotspot for the city’s gay men, many of whom worked in Hollywood alongside Rudy, a dancer. “It was a safe place for two men to have dinner together and not be stared at, ostracized, looked down upon,” Rudy’s son Robert told me. It was also good for business: “My dad saw young gay men in the ’60s as another source of revenue to keep the restaurant going,” Robert said. “That has always been the philosophy of Casita del Campo, being inclusive.”

A different ethos—activist, sapphic—defines Bloodroot in Bridgeport, Connecticut, a holdout from the wave of feminist and often meat-free eateries that had their heyday in the late ’60s. Where Casita del Campo could, on busy Saturday nights, feel like a testosterone-soaked leather bar, Bloodroot was a space where lesbians dedicated to organizing and consciousness-raising could affordably break bread. I asked Selma Miriam, who opened the restaurant in 1977 with her business partner, Noel Furie, and other women, what gave the spot its staying power. “When somebody comes in and I say ‘welcome,’ I mean it,” Miriam told me. “Especially people who are different—fat women, people of all colors and races. That’s what makes us rich.” She died in February at 89.

Then there’s Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse, which turns 77 this year. Located in Washington, DC’s DuPont Circle neighborhood, Annie’s started attracting gay customers in an era marked by lingering fears over the Lavender Scare, a two-decades-long purge of gay people from the federal government that started in the late 1940s. DC-area gays (policy wonks, Georgetown students, working-class Washingtonians) came to the restaurant for its namesake, Annie Katinas—a boisterous mama bear whom the gays loved for her warmth, humor, and heavy pour.

Among the Annie’s regulars I met was Steve Herman, a retired federal employee who had been eating there for more than half a century. Annie’s is the rare establishment these days where Herman and his friends can talk without shouting over music and reminisce about Mitzi Gaynor without having to explain who that is. During the AIDS crisis, it was a sanctuary. “It was important to be together with people who were going through the same awful things you were,” he said. “It was comforting to have a place like Annie’s to come to and cry.”

A community center with fries: That’s the secret recipe for a legacy gay restaurant that has endured, and will continue to, even as culinary and sexual mores shift. Where else can elderly gay couples eat reasonably priced roast beef specials with a house pinot? What’s better than talking sobriety with your 12-step group over apple pie? Where else to sob over a breakup than with tipsy friends and silver-dollar pancakes at 2 a.m.? Where else to be together?

in your life?

in your life?