Keisha Scarville

Higher Pictures | 45 Main Street #723, Brooklyn

On view through May 3, 2025

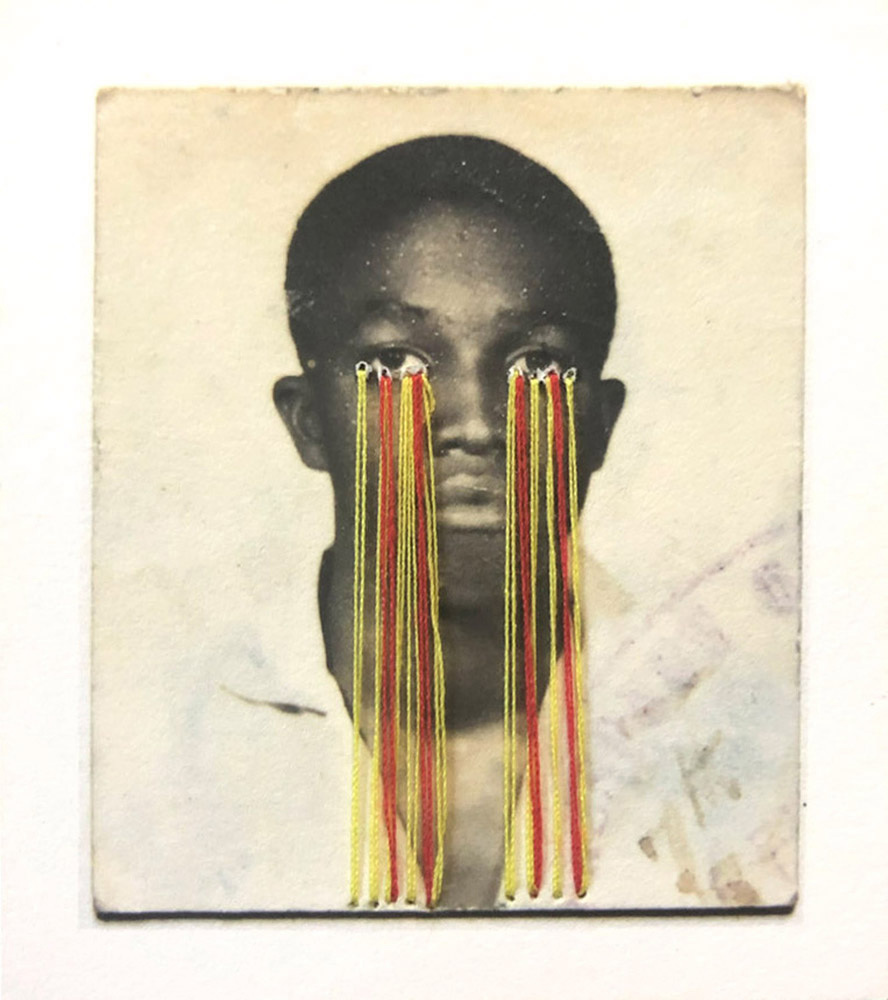

In 1951, at age 16, Keisha Scarville’s father obtained a passport in his native Guyana; in 1967, he immigrated to the United States, where he has lived ever since. In 2012—after conducting interviews that explored his relationship to his adopted home—Scarville made a copy of the photo from that first passport and adorned it. Thus began an ongoing series, now on view at Higher Pictures in Dumbo. In “Passports 2012-2025,” the most comprehensive presentation of this work to date, the Brooklyn artist’s ingeniously altered images are installed in a line along each wall of the gallery’s first room, and billow out into a large oval shape in the second, creating a powerful sense of her project’s duration.

A passport portrait both emphasizes the sitter’s distinguishing features and conforms them to a strict set of rules: The gaze must be frontal, ears must be visible, nothing must obstruct the face. In this way, the traveler’s identity becomes an iteration of a genre and is subtly flattened. Scarville dramatizes this sameness by reproducing her father’s photo over and over—322 times so far. And 322 times, she imbues these identical images with uniqueness, using watercolor and acrylic, beads and glitter, magazine illustrations and other collage elements. In one photo, her father’s mouth and eyes are whited out, in a second, a wishbone is affixed to his face, in a third, his visage is virtually occluded by swirls of paint.

Scarville’s interventions, whether reverent or playful, push beyond the visual, transforming these diminutive two-dimensional pictures into tactile objects. They become icons, talismans, things to be cradled in one’s hand. But at bottom, her inspiration remains an image—a youth at the start of life’s journey, looking into the camera and out toward the future.—Margaret Sundell

Alina Bliumis

Situations | 515 West 20th Street, 3rd Floor

On view through May 3, 2025

HomeGoods kitchen wall décor meets Magritte meets emoji slang in the dusky, dreamy still-lifes of Alina Bliumis’s show “Gut Feelings” at Situations. Food-themed visual double-entendres abound—an eggplant arcs upward behind a plump peach; a corn cob stands erect, like a bioluminescent monolith with two apples at its base; oysters on the half shell and bananas are motifs. But sexual metaphors are just the beginning, their winking allusions playing off the artist’s more subtle, or encrypted, content.

The small and medium-scale oil works, in which gracefully depicted arrangements populate indistinct interiors and landscapes, or float in strange skies (sometimes a berry soars solo), are installed on the small gallery’s white walls and expanses of worn brick. This latter, rust-hued backdrop coordinates queasily with the earth-tone and chalky pastel cornucopia of grapes, greenery, and happy snails in Fruit and Cigarette Butts via Drone, 2024, making the jarring, hidden items of the canvas’s title even harder to spot. They’re there, though, if you look: This vision of plenty (which might otherwise be at home on a wallpaper border or tea towel) is mixed with ashtray contents, and a mosquito-like aircraft hovers in the distance. The surreal composition of Mess, 2024, lends eerie geopolitical significance to another display of produce. Its pile of watermelons evokes the symbol used on social media in lieu of the Palestinian flag to evade trolls and censors. (In some feat of dystopian engineering, it seems, the melons here no longer take an ovoid form; they’re cubes.)

Deploying the still-life tradition to her own ends, the New York-based Bliumis, who moved to the U.S. from Belarus after high school, reveals her attunement to art’s fate and function under authoritarian rule. If, in the Dutch Golden Age, the genre spoke to colonial, mercantile wealth through its tabletop orgies of exotic food, in her work, images of opulence give way to commentary on war, global trade, and climate change, whispering in the lingua franca of dirty jokes and hunger.—Johanna Fateman

Aaron Gilbert

Gladstone Gallery | 515 West 24th Street

On view through April 19, 2025

Aaron Gilbert’s exhibition “World Without End” at Gladstone Gallery tells the story of the sanctity of human life persisting within capitalism. The Brooklyn-based artist’s world is tinged with the fantastical: the divine intermingled with the mundane, the mythical with the real, the human with the alien, and the solid with the transparent.

In • g • o • p • u • f • f •, 2025, the viewer looks through a crack in the wall to see the small figure of a man hunched over inside a Gopuff store, a billion-dollar food delivery company. The store’s cold, blue and white fluorescent light makes the man look as if he’s encased in ice. The wall we look through contains the greater myth, with images carved into the brick like ancient pictographs. On the left side of the wall is the figure of an alien centered in front of a large Adidas logo. On the right side are the figures of humans crowding around and lifting up a child. Barely visible are the transparent bodies and heads of serpents—which can’t escape their biblical metaphor—that run down both sides, combining them.

Compare this with the pinks and yellows of Deana and Grace, 2024, where a mother sits up in bed, doing her child’s hair, a painting which radiates warmth. (The photographer Deana Lawson appears as a frequent subject in at least a couple of the show’s dozen paintings, all oil on linen, like Deana Bathing, 2024.) The cold light of the Adidas logo appears again in The Dream Before (22), 2024, falsely illuminating the night. Above the storefront, through the bigger logo at the top, another rupture that makes another world transparent: the figure of a man holding a baby. Gilbert mingles Italian Renaissance painting with contemporary Black figuration, but this image of a parent with child reminded me of the Diego Rivera murals in the Detroit Institute of Arts, in which in one corner of the north wall, among the machines and humans at work, is a recreation of the Holy Family with common people.—Zito Madu

in your life?

in your life?