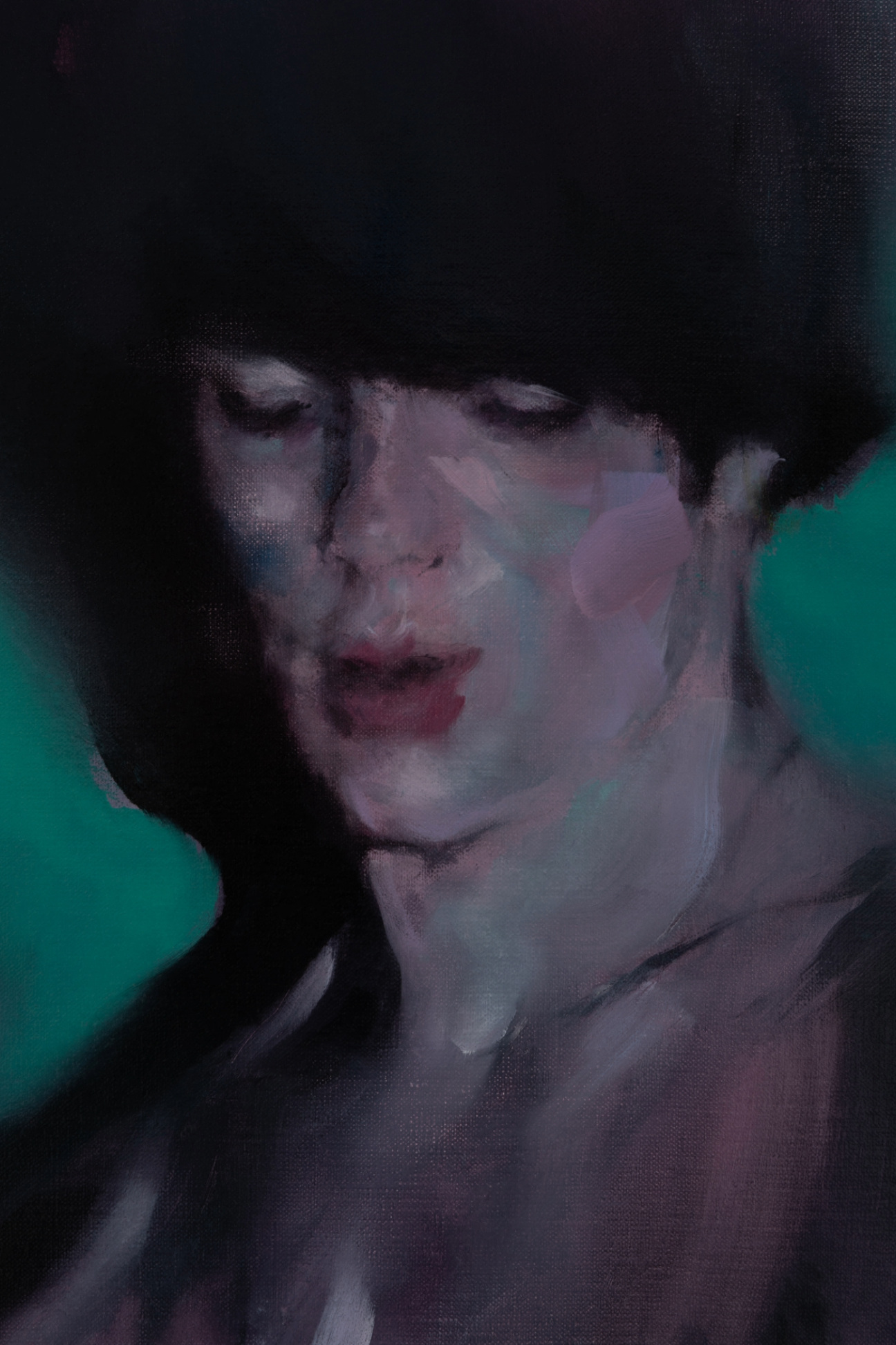

Paul P., "Sibilant Esses"

Greene Naftali Gallery | 508 West 26th Street

Through January 11, 2025

To utter this show’s title, “Sibilant Esses,” is to momentarily adopt its referenced affectation—the hyperarticulated “s” of stereotyped effeminacy in gay speech. (Try it.) The Canadian painter Paul P.’s half-joke is the icing on the cake, the final overdetermining flourish that situates his libidinal-conceptual practice foremost in a network of past homosexual styles. Overlapping eras of queer-coded visual culture fall dreamily in and out of sync with a wavering art-historical timeline here, in his Greene Naftali debut.

Since the aughts, the artist has used archival sources—particularly gay porn from the ’70s—in his small-scale portraits, favoring cropped views of faces and upper torsos. Sometimes, hairstyles (such as a Bowie mullet) date his subjects to a post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS period; sometimes, P.’s lurid palette can flag his canvases as inauthentically antique. But mostly, they are convincingly beautiful and painterly in a 19th-century (or earlier) way. The bedroom eyes and stoned grins or parted lips of lovely young men—rendered with the age-old soft-focus technology of oil paint—emerge from an erotic, elegiac haze.

These recent figurative canvases triangulate with two other categories of irresistibly gorgeous work (all are irritatingly untitled). One group shows pastel swaths of sky, bats flying in the crepuscular light; the other is composed of dusky near-abstractions, gauzy geometries inspired by the stucco passageways of Venice at nightfall. Greater than a sum of its parts, “Sibilant Esses” is a poignant and timely gift for a dawning era, when the need may again arise to establish belonging or alienation without words but with a sissy’s hiss.

Jes Fan, "Sites of Wounding: Interchapter"

Andrew Kreps | 55 Walker Street

Through December 21, 2024

A DIY endoscopy, projected onto the surface of boiling soy milk; gnarled 3-D prints of the artist’s own CT-scanned musculature; and tofu skin hung on metal armatures like drying racks—these are a few highlights from Jes Fan’s impressively varied, complexly cohesive new exhibition at Andrew Kreps. (It is the Brooklyn and Hong Kong-based artist’s first solo show in New York.)

The fantastic corporeality of Fan’s art begins with the visualization of interior space, but it ends somewhere else. The tabletop sculpture Right pelvis, Cross Section, 2024, for example, is an object of transfixing ambiguity, appearing both fabricated and fossilized, and, with its jumbled orifices and protuberances, like both an animal and a mineral—if not a vegetable, too. Similar to his other radiologically captured body parts, printed with tree-bark-hued plastic and punctuated with blobs of glass (some of which were featured in this year’s Whitney Biennial), Right pelvis has the presence not of a static specimen, but of a hibernating organism waiting to rejoin the biosphere as a new thing.

It's the global cash crop of soy, though, with its alchemical potential for transformation, that underscores the thrilling material instability of Fan’s show. Here, we see soy, in liquid form, functioning as a murky scrying mirror (as the horizontal projection screen for the aforementioned intestinal film). Then, in a corner, individual soybeans have been given the pharmaceutical treatment, placed in transparent gelcaps, and, like a Felix Gonzalez-Torres candy piece, piled in a corner on the floor. Finally, draped lengths of yuba—coagulated sheets skimmed from boiling soy milk—recall Eva Hesse’s post-Minimalist experiments with latex. Fan’s rich futurism comes into sharper focus when viewed through the lens of such radical forbears.

Sylvia Plimack Mangold, "TAPES, FIELDS, AND TREES, 1975–84"

Craig Starr Gallery | 5 East 73rd Street

Through January 25, 2025

The great painter Sylvia Plimack Mangold, now in her late 80s, discovered early in her career that the mundane can be infinitely generative, that boundlessness may be found in constraint. For decades, she has taken as her subject a single maple tree, visible from her studio, with alternately glorious and gloriously austere results. (It depends on the season.) “Tapes, Fields, and Trees, 1975–84” at Craig Starr is a concise exhibition that—as the title implies—includes work predating her exclusive focus on the maple. But her inimitable, exacting approach is no less formidable, and the variety of work on view here, from a fruitful nine-year run long ago, delivers surprising drama.

In the gallery’s front room, small and medium-scale paintings from the ’70s show the artist experimenting with what’s right before her eyes. Plimack Mangold depicts the pale parquet floor, capturing the woodgrain with trompe l’oeil precision; a sheet of graph paper; rulers; and a spiral-bound notebook page, tellingly inscribed with three lines of handwritten commands (or a poem): “paint the tape / paint the paper / paint the tape.”

Masking tape—realistically painted, not real—is the common thread here. It frames or crops every composition, even as Plimack Mangold retrains her gaze, looking out the window at last. In the next room, trees enter the picture. A wonderfully drab view of a leafless pin oak, from 1984, is perhaps my favorite, but the wall-spanning A September Passage, from the same year, packs more of a punch. It’s shockingly verdant—a sweeping landscape that, after the absorbing subtleties of graph paper (et cetera) seems almost overwrought.

in your life?

in your life?