"Bad Girls" through December 8, 2024

OCDChinatown | 75 East Broadway Mall, 2nd Floor

Sharp, glimmering pins pierce the corners of Fern Cerezo’s two self-portraits in OCDChinatown's group show “Bad Girls,” which has been lovingly assembled by Devan Díaz for her curatorial debut. The pair of commanding images join photographic works by five other artists, mounted on the walls around a high-heel shoe sculpture by Jessica Mitrani at the gallery’s center (a glossy black platform, glitched out to ankle-breaking height and displayed on a Lucite plinth). “That accident which pricks me” is how Roland Barthes describes the punctum, but the prick—that detail of stirring, intense unexplainable affect—in Cerezo’s work is no accident, it’s the stare: vulnerable, stubborn, fuck me, fuck you! The politics of rEPresEntAtIOn boiled into a look. A sense of mortality shadows this attitude as it does the thrillingly vulgar pink that Díaz has painted the space, an allusion to the house from Camila Sosa Villada’s novel, the 2019 trans bildungsroman Bad Girls, after which the show is named. Díaz chose an orange-pink shade like sunset that makes the black of the frames and the shoe go pop.

Díaz takes on two trending genres here—shows that take books as their premises, and those composed of Downtown glamor-portraits—managing to birth something in lockstep with the climate yet still all her own. Who the people are in these photos is as important as who the artists are to one another as it is how they make each other look and how that makes them feel. A shared language of beauty serves as the show’s connective tissue—many of the artists have worked on both sides of the camera.

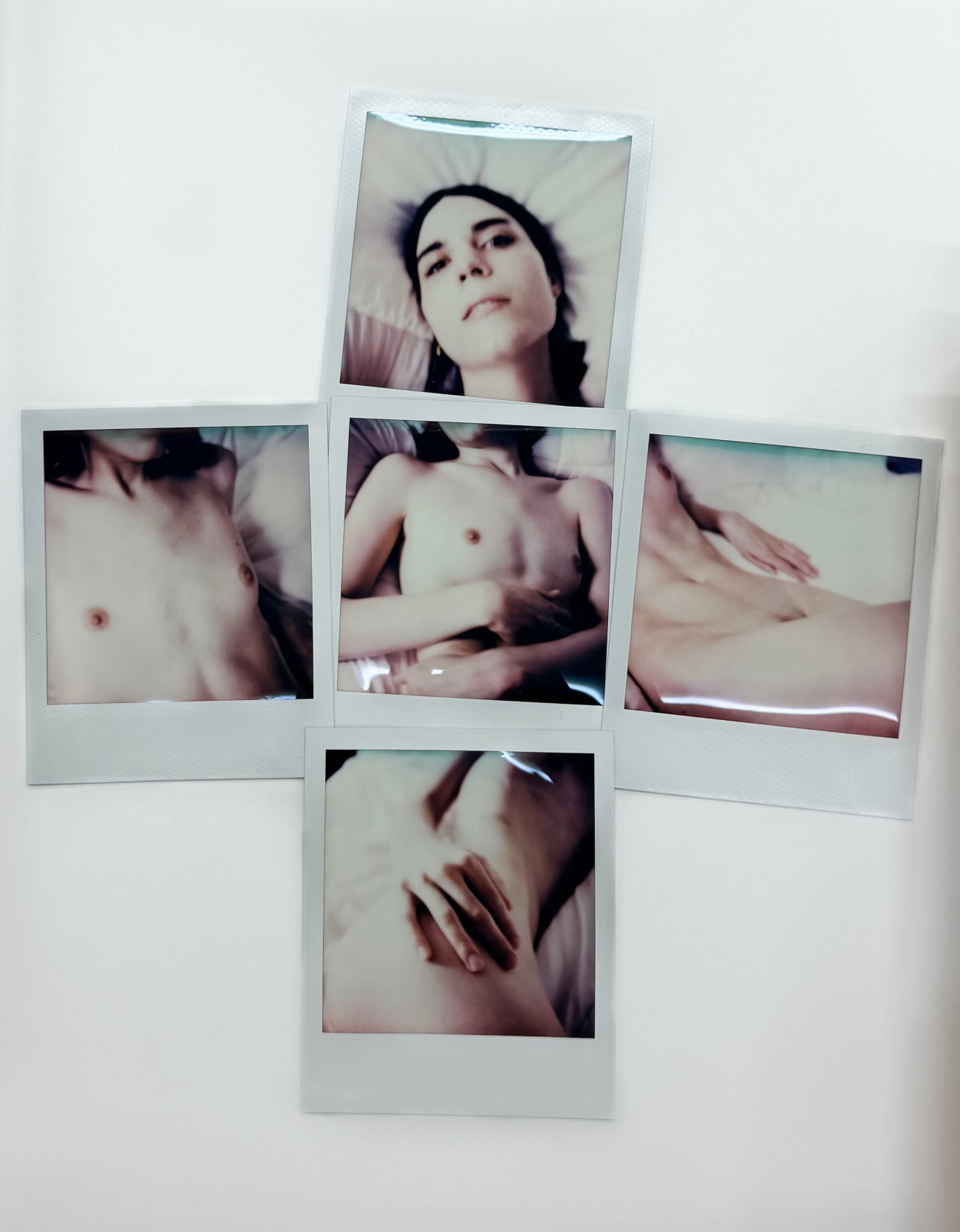

While there’s a timeless appeal to lens-based virtuosity across the mostly black-and-white images, they’re not all easily digestible. Even with the possibility of violation in Reynaldo Rivera's private dressing room photo (from 1993, which makes it older than most of the artists in the show), it’s Cruz Valdez’s self-portrait that’s the most quietly menacing: Her naked body defiantly straddles an inscrutable metal pyramid, its point pressing into her genital slit. Valdez is also the subject of a Polaroid collage by Sebastian Acero that fragments her body into five squares. In “Bad Girls,” the violence of photography is ever-present—exposed, turned back on itself, used as tool of glamor—but never completely pinned down.

—Whitney Mallett

Janet Olivia Henry, "Six Decades" through December 15, 2024

Gordon Robichaux | 41 Union Square West, #925 and #907

In the 1980s—when she wasn’t teaching, working at Just Above Midtown, or participating in the Women’s Action Coalition—Janet Olivia Henry transformed her art by incorporating craft traditions such as beading, weaving, sewing, doll making, and quilting into sculptures. Several of her thick, hanging compositions—on view across two gallery spaces at Gordon Robichaux in her show "Six Decades"—incorporate a riot of texture and color. They also include snippets of scripts—as slim “pillows” stuffed and sewn together with vinyl—taken from her satiric fictional narratives on race, gender, and class about symbolic characters such as the White Protestant Male and the Christian Colored Lady.

A consummate storyteller with a poet’s precision, Henry has worked for six decades on process-driven sculptures and installations that offer a playful yet biting critique of American culture. She is perhaps best known for her dioramas of miniature toys, everyday trinkets, and dolls, yet, as her most comprehensive solo show to date makes clear, there is so much more to her practice. Take, for example, her early portraits of people made with found objects and personal items in distinct color schemes (green and red, for instance) that could be encased in small “juju boxes.” Or, consider her more recent hanging, talismanic sculptures incorporating strands of beads from around the world held together by a Japanese knotting technique.

Down the hall from the earlier work, four of these knotted pieces are given a room of their own. These surround her latest diorama, Crystal Casita, 2024, a self-portrait of the artist as a plastic Black doll at work in a studio walled off with translucent Legolike bricks. The piece nicely echoes the oldest work in the show, Juju Box for Myself, 1976, which equally forefronts kitsch and low-cost aesthetics through an array of tiny, timeworn objects. What does it mean to be making art that shuns the bigness and swagger of today’s art world? Maybe she’s just having fun.

—Lauren O'Neill-Butler

Nour Mobarak, "Dafne Phono" through January 12, 2025

The Museum of Modern Art | 11 West 53rd Street

An overly bumptious Apollo is struck by one of Cupid’s arrows and falls for the nymph Dafne, who is also struck but, in her fashion, to hate her admirer. She sculpts a plea to the other gods to stop Apollo’s mad pursuit, and they comply by transforming her into a tree. So goes the fable, more or less, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which is the basis of Jacopo Peri and Ottavio Rinuccini’s Dafne—the first ever opera, from 1598. It's also the premise of Nour Mobarak’s exhibition “Dafne Phono” at the Museum of Modern Art: The Lebanese-American artist’s 15 singing sculptures perform a multilingual translation of the 16th-century work.

Across sculpture, sound, video, writing, and performance, Mobarak’s practice concerns the mutable vehicle for meaning making that, when using our words, we call voice. Working with native speakers across the globe, Mobarak recomposed the libretto in several morphologically expansive, endangered languages: Apollo retains the original Italian, but Cupid speaks Abkhaz; Venus whistles in Silbo Gomero; Dafne, the West ǃXoon dialect, Taa; and the chorus, a mix of everything, including Eastern Chatino. Each voice emerges from the gullet of an individual sculpture. Mobarak grants some characters simple geometric forms, while others are made figural, such as a cherub and a serpent. Nearly all are enveloped in living saprophyte, a mycelial fungus that feeds on the nutrients of dying wood to make its fanlike, fruiting body. These branching filaments mirror the colonizing inroads that language itself makes, as it perverts, oppresses, and determines. The tree Dafne, a snaking chain of truncated columns, makes her way, partially suspended, toward the heavens like a line of poetry left incomplete, or strung together from those parts of speech that both save and sentence her.

Mobarak reverses the recitative form of opera, which makes music resemble the spoken word: In Dafne Phono, the aspirations, fricatives, and glottal stops that emanate from the buccal planet of the mouth become a song to surround you. Even when I investigated a hole cut into the wall, I heard a sharp, sucking sound—that void is Ovid. Nowhere, in Mobarak’s cosmos, is there nothing.

—Shiv Kotecha

in your life?

in your life?