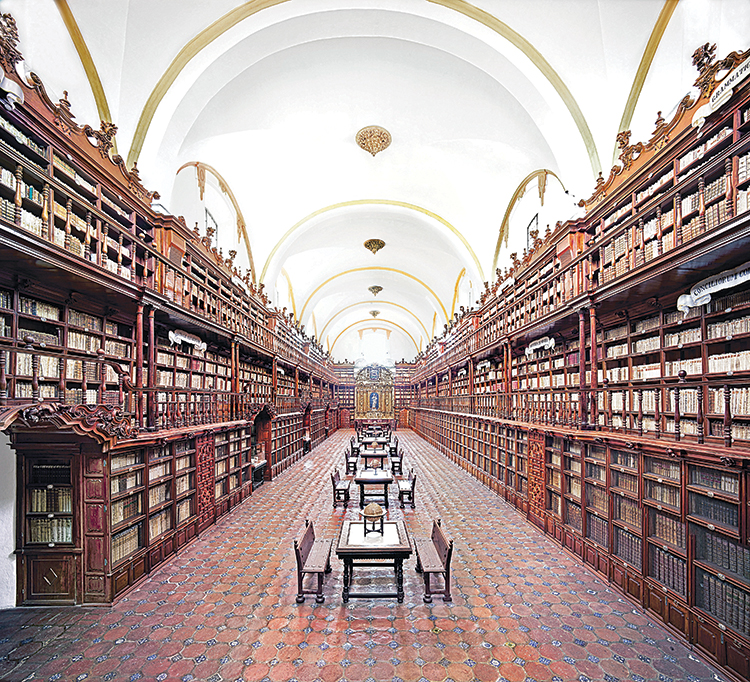

Whereas fellow German photographers like Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky skulk industrial environments or populated pop palaces (from laboratories and museum halls to Disneyland rides and Madonna concerts), Höfer prefers to capture what seem to be moments of golden silence in spaces intended for reverie—be it grainy afternoon light spilling into a Rudolph Schindler house in Los Angeles and moody shots of empty salons in Florence’s Palazzo Medici or UltraHD renderings of the iconic interiors of Dusseldorf and the hypnotic helicoidal atrium of Mexico City’s gleaming Edificio Basurto.

“She always says that she’s not an architectural photographer, she takes portraits of buildings. There is a difference between one thing and the other,” adds Monasterio. “Definitely for us to have Candida accept to do a project in Mexico is a very important thing for Mexico. I think that what she accomplished is really capturing the human footprint in an empty building, how people live in that building, how they worship, how they appreciate art or history without seeing people actually doing it. You can’t see the passage of time, you can’t see the passage of people and even though it’s cold and perfectly planned she does capture the soul of the building.”

To accomplish this lofty goal, Höfer is methodical and unshaken in her approach. She prefers to work with natural light and relies only on the artificial illumination indigenous to the buildings she shoots, opting to stitch together the most cinematic fragments of her images in the studio. In Mexico, she also had the advantage of shooting extremely resolved digital portraits, as opposed to the analog images she was taking when she first arrived in the country.

“There are so many things in these places, but I want to show that most have these repetitive elements and these elements can be distinctive in their repetition,” says Höfer. “My impression is that in Mexico red is very important.”

Color may be the most conservative part of these buildings. “If you think of German baroque, it’s a lot more sober than Mexico is. When you walk into a church in Germany the walls will be white, the sculptures will be stone or black, but there’s nothing to compare it with the Mexican baroque, which is full of figures, full of floratura, clouds and stars and flowers and fruit,” says Monasterio. “Mexico in general as a country and a cultural expression is quite chaotic, and she took her lens and put an order to that chaos.”

Though her photographs—in Mexico and beyond—may very well be worth much more than a thousand words, Höfer, who sports her signature bob dressed in her signature black, is economical (if not austere) with her own verbalizing. Over the course of our breakfast her husband, Herbert Burkert, offers numerous translations to her, interpretations for her, and even gives some photo direction—”Don’t look at the dog, look at the camera… Maybe you step back… This is perfect with the reflection of the umbrella”—to his wife when a fan approaches to take a picture with her. Though she reluctantly indulges this impromptu shoot, it’s clear that Höfer seems much more at home in unoccupied spaces without fans asking favors and journalists asking questions. Perhaps it’s always been thus. Höfer trained at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf under Bernd and Hilla Becher, the hohepriester of ordered architectural taxonomy, and began her own career by showing a slide projection of photographs from her late 70s breakout series, Türken in Deutschland, a durational project which captured the lives of Turkish migrant workers living around Germany.

“I found out it was too difficult for me to impose an order them,” says Höfer, whose obsession with vacancy began in earnest during the making of this project. “But during this time I took some photographs of Turkish restaurants—sometimes with people, sometimes without people—and I really liked this.”

Though she didn’t plan on it then, and doesn’t plan on it in the future, some of the images from “In Mexiko” were unexpectedly populated. “At the library in San Carlos I only had a chance to take photographs during normal business hours so there were people in the photos and they look like ghosts because of the long exposure time,” says Höfer. “This place had a sort of closed, boarded atmosphere so the ghosts are quite becoming. But I wouldn’t say this is a turning point.”

What may be a turning point for the photographer is her recent interest in using a small handheld camera to document street scenes and take snapshots of quaint details—graffiti, construction scaffolding, fluted windows, skylights—inside and around unstaged buildings. “At the moment I’m thinking about what can I do different,” says Höfer. “But I’m still in the process.”

While the large format works in Mexico required veritable film productions with teams of assistants—not to mention Monasterio and Riestra, who are co-curating the San Ildefonso exhibition—these candid shots from around the country offer a visual punctuation—or “confusion” according to Burkert—which the artist welcomes. She’s even welcoming the possibility of extending the project into the future, as she mentioned during the press conference for UBS, who is sponsoring the project.

“It’s only the first step in a project that has a lot more to give,” says Monasterio. “There are over 400,000 churches registered and we only photographed five of them. It’s only a taste.”

in your life?

in your life?