With modernity have come myriad mechanisms to avoid the intrusions that accompany city life. Noise-canceling headphones, tinted car windows, dishes delivered (contactless) at all hours of the day—these are just a few of the amenities that pad an increasing number of users’ experience of a Babylonian capital like New York.

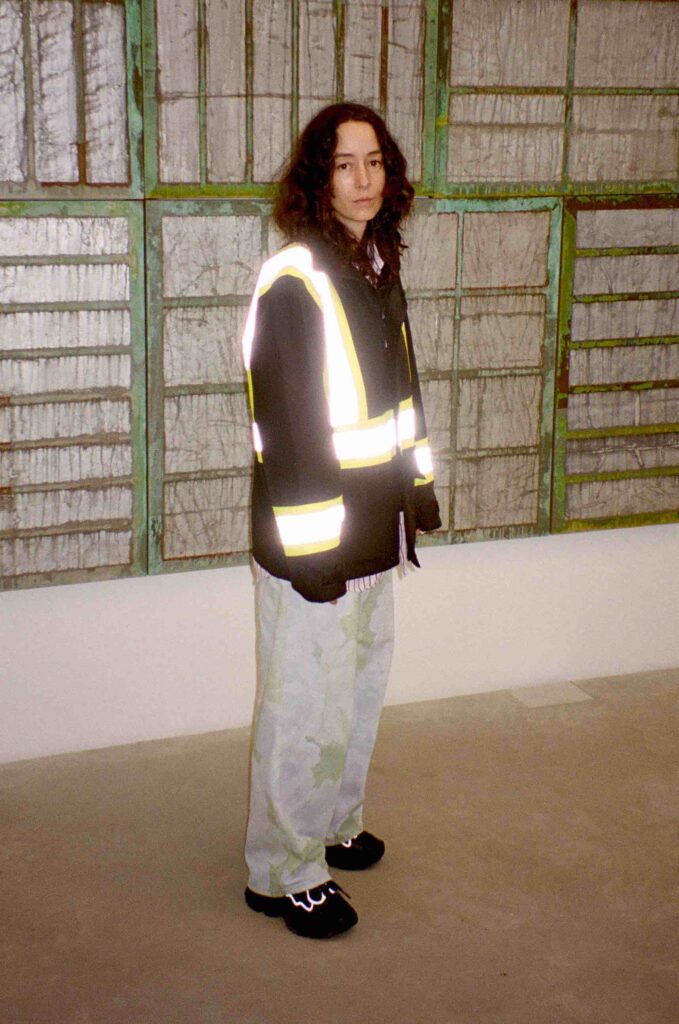

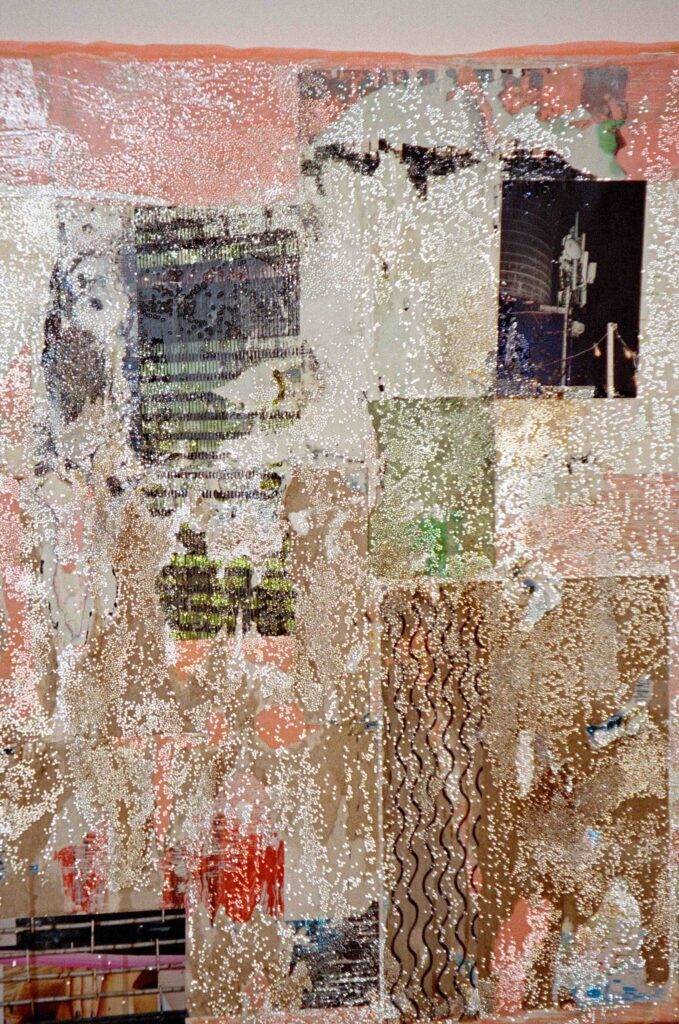

Smell, however, has remained a stubbornly (and often hilariously) uncircumventable sense. Come October, New Yorkers of all stripes will participate in the rare collective exercise that is inhaling fallen female gingko seeds. (The trees, which outlived the dinosaur as a species, make up roughly 10% of the canopy in Manhattan alone.) As iconic as they are fodder for complaints, gingkos are an apt metaphor for how people feel about the city itself—and one of the leitmotifs of French artist Mimosa Echard’s dissection of New York, “Facial.” The show, on view at Amant today through Feb. 16, 2026 (peak gingko-smelling season), sees Echard siphoning her often pedestrian perspective of the metropolis into an entirely new series of palimpsest-y canvases, as well as a video work of Times Square, abstracted.

The botanical realm is familiar territory for Echard—who usually works out of a studio with a garden outside of Paris—as is the digital. She cemented her position in an ascendant and anarchically online generation of French artists by winning the Prix Marcel Duchamp in 2022 with a leaky video work about life cycles, menopause among them. At Amant, she has trained her lens on another classically “feminine” setting: the beauty salon. The repetitive eye-conography, if you will, on the façades of almost every aesthetician in New York (almost always accompanied by a security camera) triggered a meditation on “sweet surveillance” that’s a throughline of the show. Here, we unpack that concept as well as the unexpected comedown of winning a prize, and why New York is a sexy jail.

CULTURED: I read an interview where you were talking about your garden in Nogent-sur-Marne, near Paris, and you said, “There is always some part of my brain there.” We’re thousands of miles away, in East Williamsburg. Where is your brain today?

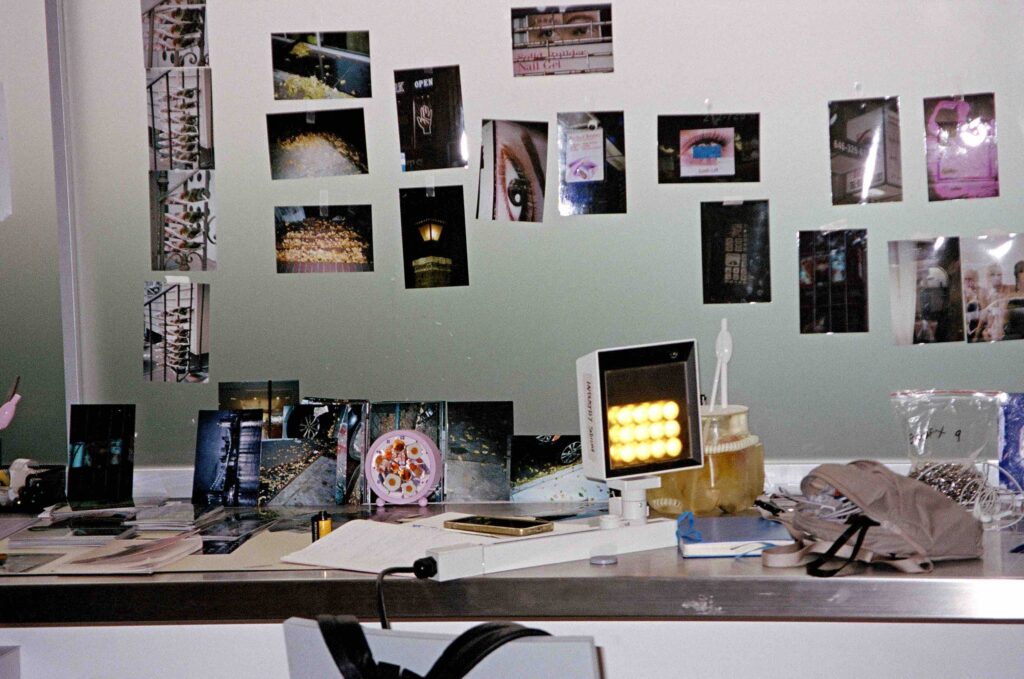

Mimosa Echard: I’ve been working here for about two months now, between Amant and another studio in the neighborhood. I have a friend who’s taking care of my garden for the summer—he’s an artist who usually lives in Brighton Beach. It’s a fun swap. This neighborhood is very industrial but also very funny. You have this concrete factory called Gotham Ready Mix with big trucks, and then you have clubs. It’s an epic neighborhood… pretty fascinating. It’s kind of like the factory of the city. You see tons of merchandise, but also a lot of artists around. So it’s also like the artist factory. I was mostly gravitating around Manhattan at the start of the project. But since I work here, I became kind of inspired by this place too.

CULTURED: Where in Manhattan were you gravitating to?

Echard: I was pretty much everywhere. I was walking a lot. I really feel like New York is a character, but also like a formal object that artists gravitate around. Being here, I felt connected to a lot of art history—formal and conceptual practices. I started to take pictures of beauty salons. I noticed that the same image of the same eyes, probably an open-source image, was printed all over the city. I also started photographing ginkgo leaves when I arrived, which had just started falling. It was amazing to see the dispersion of the leaves with the coal, the pollution, and the city. I’ve been interested in ginkgos for a long time. It’s the only living species that survived the atomic bomb. But also, they have this really ancient type of sexuality. They’re really living fossils.

CULTURED: Gingkos are also known for their smell.

Echard: That was also something that I was interested in, how people react so strongly to it. And you know, it’s the female egg that smells. But people won’t get rid of the gingkos. I was intrigued, like, why are there so many gingkos in New York? I think it’s something like 9% of all trees in New York are gingkos. They choose them because they’re resistant to pollution, pretty easy to maintain, and also resistant to insect invasion.

CULTURED: And tell me about the beauty salon façade eyes. They’re looking at you, but they can’t really see.

Echard: In most of the pictures, you can also see a security camera. There was something about having this almost paranoid story where you walk around the city and you see the same big eyes with makeup looking at you. The circulation of images is something I’m really interested in. The whole show is about circulation and exposure. This idea of “sweet surveillance”—almost like a security camera wearing makeup—was also part of it.

The show’s title, “Facial,” was about the question: What is a face? It’s written on billboards usually, you know, like “waxing” or “facial.” I liked the dispersion and circulation of this word in the city, but also that it gravitated around public and private, surveillance or pornography, but also self-care.

CULTURED: Did you go inside any of these salons?

Echard: I haven’t, actually. But I have to.

CULTURED: I guess that makes sense since most of your work is about the surface, not the inside experience.

Echard: But I think you’re right, I’m also interested in trying.

CULTURED: How has your mode of working been affected by working in New York?

Echard: I’ve been working with New York for a long time. The piece I made for the Prix Marcel Duchamp was also related to New York. In Paris, I’m more in my bubble. You were talking about my garden, of course. With this project, I decided to be quite vulnerable and make everything here during two months. And also to let myself be exposed to what I don’t know.

CULTURED: That porosity is interesting in New York, because with exposure, you feel very alive but not very protected. It’s a very dense and often inconvenient experience but also exhilarating.

Echard: Yeah, it’s kind of like a drug.

CULTURED: You have to be a bit delusional to live here.

Echard: A friend of mine calls it the sexy jail.

CULTURED: That’s good. Rem Koolhaas would say it’s like an amusement park.

Echard: When you go to Times Square, it’s kind of old and rusty. I filmed the screens there for a video in the show, but really close up so that it becomes abstract.

CULTURED: Times Square is so broken. Only the images are sleek. Like gingko trees, it’s also pungent. I read that you used urine in some of the pieces in this show?

Echard: I did use it in these [points to artworks]. It’s urine that becomes almost fossilized in epoxy. It’s a chemical reaction between the epoxy, which is super toxic, and the urine. I also used beauty salon wax, because they have fantastic colors. I was making layers between the wax and the urine. I was really interested in how urine circulates in the city, because it’s full of information like hormones, trace minerals, etc. I made a big wall piece out of anti-radiation fabric that’s used to build shelters off-grid. I was thinking about how electronic waves are penetrating us all the time, and this idea of purity and impurity, what is clean and what is not, really working with the materials of paranoia. To me, paranoia is quite close to an artistic process, you know, making systems, working with analogies, being really attentive to signals, trying to make weird connections…

CULTURED: Is there a phase of your work where you feel the most paranoid?

Echard: I mean, to be clear, I’m not paranoid in a psychological way, but I guess when I’m really alone for a long time in my studio, it can become… weird. It’s like a rabbit hole.

CULTURED: The press materials for the show mention the idea of the flâneur. It’s a mode I associate more with Europe—this ability to wander. Here, it feels much more paranoid and fast-paced. You were wandering around Manhattan; what was your experience of being a flâneur in New York?

Echard: It is kind of anti-flâneur, completely. But there’s a sentence by Walter Benjamin that compares the city to a forest. It kind of works with New York, if you take it as a weird, mysterious machine. You can get lost, you can be really attracted to a specific detail.

CULTURED: You won the Marcel Duchamp Prize in 2022. It’s been three years. What did that change for you, other than exposure?

Echard: It kind of created a void more than anything else. I was super happy to get the prize, of course, and I had such an amazing time working on the piece I showed for it. The Viennese writer Thomas Bernhard said, “When you win a prize, it’s like people are shitting on your face,” or something like that. There is something strange about it. People react strangely, like, “Are you happy now?” But I’ve never worked for prizes. I’m just focused on the work.

P.S. If you can’t make it to Amant before February, Echard’s first monograph is out with Mousse now, and she’s got two upcoming shows in Shanghai and Basel next year.

in your life?

in your life?