Wilson W. Smith III is Nike’s best-kept secret no more. Those in the know have often described him as the Jackie Robinson of the athletic footwear industry: the company’s first Black designer, who created shoes for the likes of Michael Jordan, Andre Agassi, Roger Federer, and Serena Williams.

The athletic footwear industry is notoriously tightlipped, fiercely guarding trade secrets and top talent. But after a 41-year run at Nike, Smith retired this winter and is seizing the moment to reflect on his career, giving one of his first interviews to CULTURED.

Born and bred in Oregon, Smith graduated with a degree in architecture from the University of Oregon and began his career at the Portland office of the architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. After being laid off in 1983, he interviewed with U of O alumnus and Nike corporate architect Tinker Hatfield. After spending two years designing showrooms, stores, and offices for the company, he followed Hatfield into shoe design in 1985.

There were no wrong moves in the ’80s and ’90s for Nike—Jordan was signed in 1984, ad agency Wieden and Kennedy coined the phrase “Just do it” in 1988, and, in 1990, Nike moved into their World Headquarters and launched their first immersive retail environment, NikeTown, in downtown Portland. In the ensuing decades, Nike has dominated the categories of running, basketball, and American football. And Smith made his name designing shoes for some of the biggest tennis stars in the world.

During the inaugural Sneaker Week in August, the Portland Art Museum hosted a celebration honoring Smith. We were introduced and later sat down for a conversation exploring the intersection of architecture and sneakers.

What was your favorite toy growing up?

I drew a lot of pictures and played with building blocks. When I was 5, my mom said I should be an architect because architects make a lot of money. [Laughs] She didn’t want me to be a starving artist nor squelch my love of design and curious nature, so architecture from grade school to college became my North Star.

What is one of your earliest architectural projects for Nike?

Tinker [Hatfield, Nike’s corporate architect] designed the Nike 1984 Olympics Store in Westwood, Los Angeles. One of the main elements was a huge swoosh crashing through the front facade. On the odd day that it would rain in LA, water would trickle down the swoosh and into the store. I developed a gutter for the swoosh, a clear plastic sheath that captured the run-off. I got a couple of trips to LA for that!

What Nike project was a game-changer for you personally?

In 1984, I designed a new retail concept that Nike named the “factory store.” The very first one was in North Portland, a vibrant Black neighborhood. No one had invested in this area, and Nike set its intentions on building community by hiring from the community and creating neighborhood initiatives. I detailed a lot of odd angles for the interior, and I recall founder Phil Knight attending the opening to cut the ribbon. At that time, the significance was lost on me, but today there are hundreds of Nike Factory Stores around the world, and I’m proud of my contribution.

Was it easy to pivot from architecture to shoe design?

In 1986, I was called into a back room, and thought I was going to be laid off. Instead, they said, “Do you want to design shoes?” and I said, “I’ve always wanted to design shoes!” I had never considered designing shoes. I was a snobbish architect, and architecture was considered the highest form of design expression. But sitting next to Tinker, an architect who was so adept and thorough, he saw it as a practice of designing homes for the feet, shoes were like little buildings. And it was a revelation that I was as fulfilled designing shoes as I was designing buildings.

Are athletic shoes overdesigned today?

Your question reminds me of what a good friend, a pastor, said to me: “When I heard you and Tinker, two architects, were starting to design shoes, I thought shoes were going to get complicated.” When design prioritizes style over story and style over performance, we lose something. For me, the best architecture is one that is attached to function and context, and so it is with footwear design.

Our feet represent the place where our body meets the earth. And this is the point where you need to identify all the forces in your movements in the sport. It’s a sacred design opportunity, but also we have to get out of the way and let the foot be the foot.

You’ve had a long chapter designing shoes for the GOATs of tennis. How did that come about?

I grew up playing basketball and loved tennis in college. At one point, management offered me the opportunity to help lead tennis or basketball, and basketball was well established, arguably Nike’s second most important category after running. Running is the heart of Nike, and basketball is the soul. Basketball was a big deal with a lot of eyes on it. Tennis—there was less pressure. And honestly, a Black guy doing a basketball shoe felt expected. Moving into the tennis world was an opportunity to bring some diversity into a sport that lacked it.

My goal was to become Mr. Tennis, and I found a world of joy in building relationships with Andre Agassi, Pete Sampras, Mary Joe Fernández, Monica Seles, and Mary Pierce.

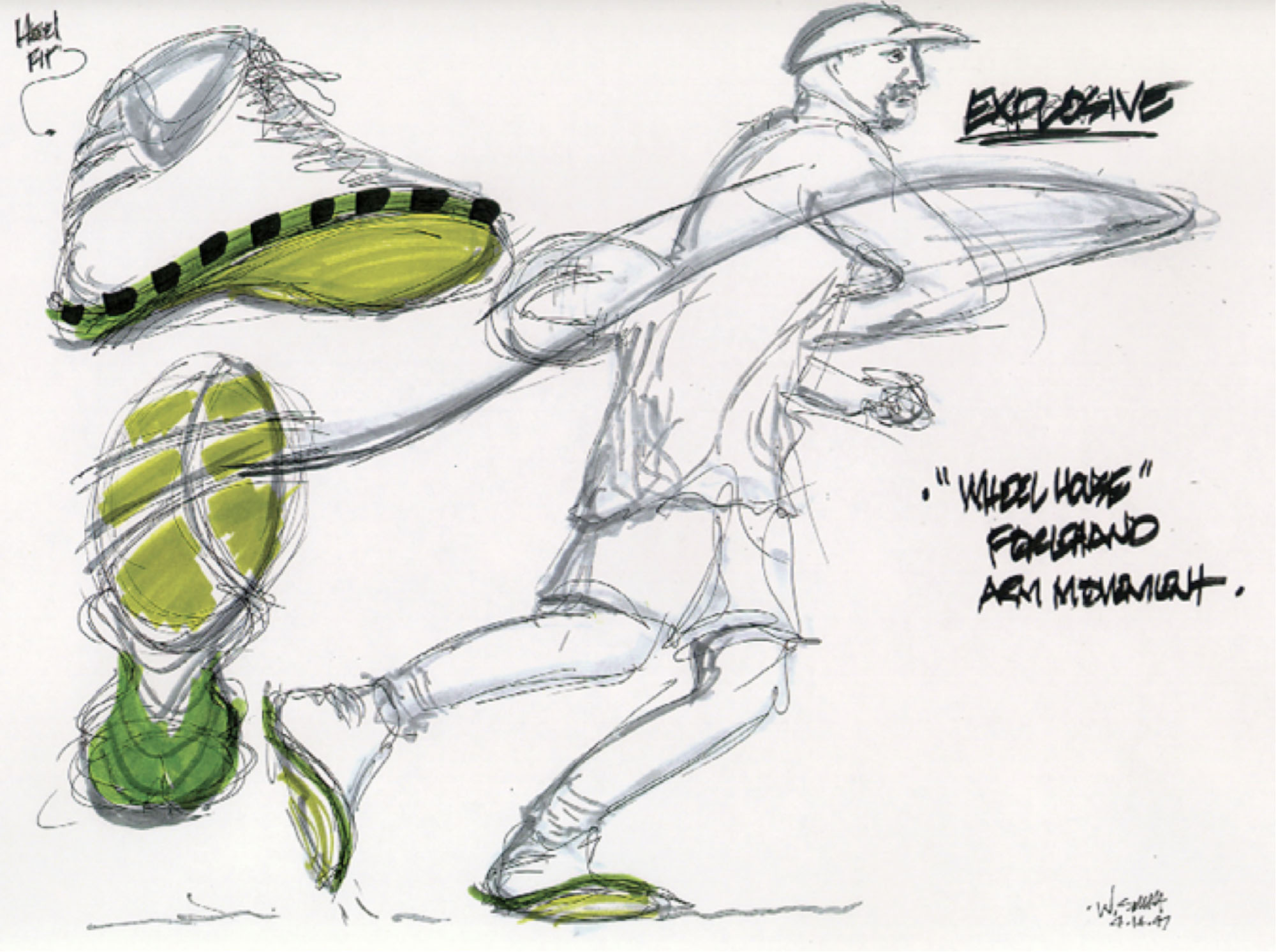

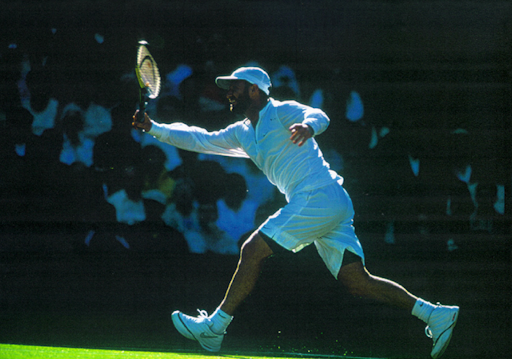

You had a deep design run with Agassi. What was that like?

From 1994 to 2001, I designed a shoe for Andre every six months, a collection of 15 or more shoes. It’s fun to develop a storyline from one shoe to the next, and we were always trying to bring to light something Andre was into, as well as a new performance insight. And we discussed beauty and the shoe; ultimately, beauty needs to perform.

If shoes are little buildings, you designed a skyscraper for Serena!

Serena is wonderful, and she helped build a new era, a new evolution for Nike. [The largest building at Nike HQ is named after her.] I met her in October 2003, and she signed with Nike in December of that year. We had 10 months to design a shoe for her to debut at the 2004 U.S. Open. I asked my boss, Mark Parker [who became CEO in 2012 and retired in 2020], what he would do differently when designing for Serena. He suggested letting her sense of fashion fuel the performance design—make that the innovation.

Over the winter months, Serena was always wearing boots, and I said, “What about a tennis boot?” She signed up for the concept and then I took the sketches to the Nike Sports Research Lab. Sure enough, they were also interested in a tennis boot. We treated the boot as a long sock with a bottom stirrup, which warms up her calf muscles to prevent cramping, mimicking a compression sleeve that can be easily zipped off.

And the Serena boot becomes infamous. Why?

It’s a nighttime session, and Serena walks out in the Arthur Ashe Stadium in a Nike-designed denim tennis skirt—channeling Agassi—a studded tank top, and a pair of black boots. The cameras are flashing like she’s on a Paris runway. Tournament officials deemed them too dramatic to be worn during matches, so she warms up in them, zips them off, and goes on to crush her opponent. Later that evening on ESPN’s SportsCenter, Serena and the boots are featured, and the next day, on USA Today’s front cover, in the upper left-hand corner, there was a close-up of the boots. Our takeaway: Serena had the ability to tell stories and influence culture way beyond the sports world.

With the growing popularity of hip hop and basketball, collecting sneakers became a trend during the 1980s. Some say it was legendary DJ and basketball enthusiast Bobbito Garcia who coined the word “sneakerheads.” What’s your role in this cultural phenomenon?

I surfed the wave of Nike’s culture, starting as an architect, and became a storyteller. Later in my career, I was a key team member of the Department of Nike Archives (DNA) and at one point, my title included the word “sneaker” in it. I was initially taken aback; the word “sneaker” felt informal, but really, it’s a cultural concept. Sneakerheads are kids who grow up loving the stories around each release and how it connects to their own journeys. As an older person, they can actually afford sneakers, collect them, and it’s a nostalgic connection.

Do you collect anything?

Besides pounds? On a more serious note, I never had my own children, but I’ve taught hundreds of students over the past 15 years. Not so much a collection, but rather a collective where I can be an inspiration and share my experiences to help empower the next generation of visionary designers.

in your life?

in your life?