It’s late in the day and the sun is pouring into Raúl de Nieves‘s spacious Williamsburg, Brooklyn studio. Through the windows, the Manhattan skyline is framed like a poster one might find in an Airbnb—an apt, if somewhat ironic, symbol of the ascent this queer Mexico-born artist has experienced in recent years. But it’s not success that’s on his mind these days. What he’s thinking about is failure.

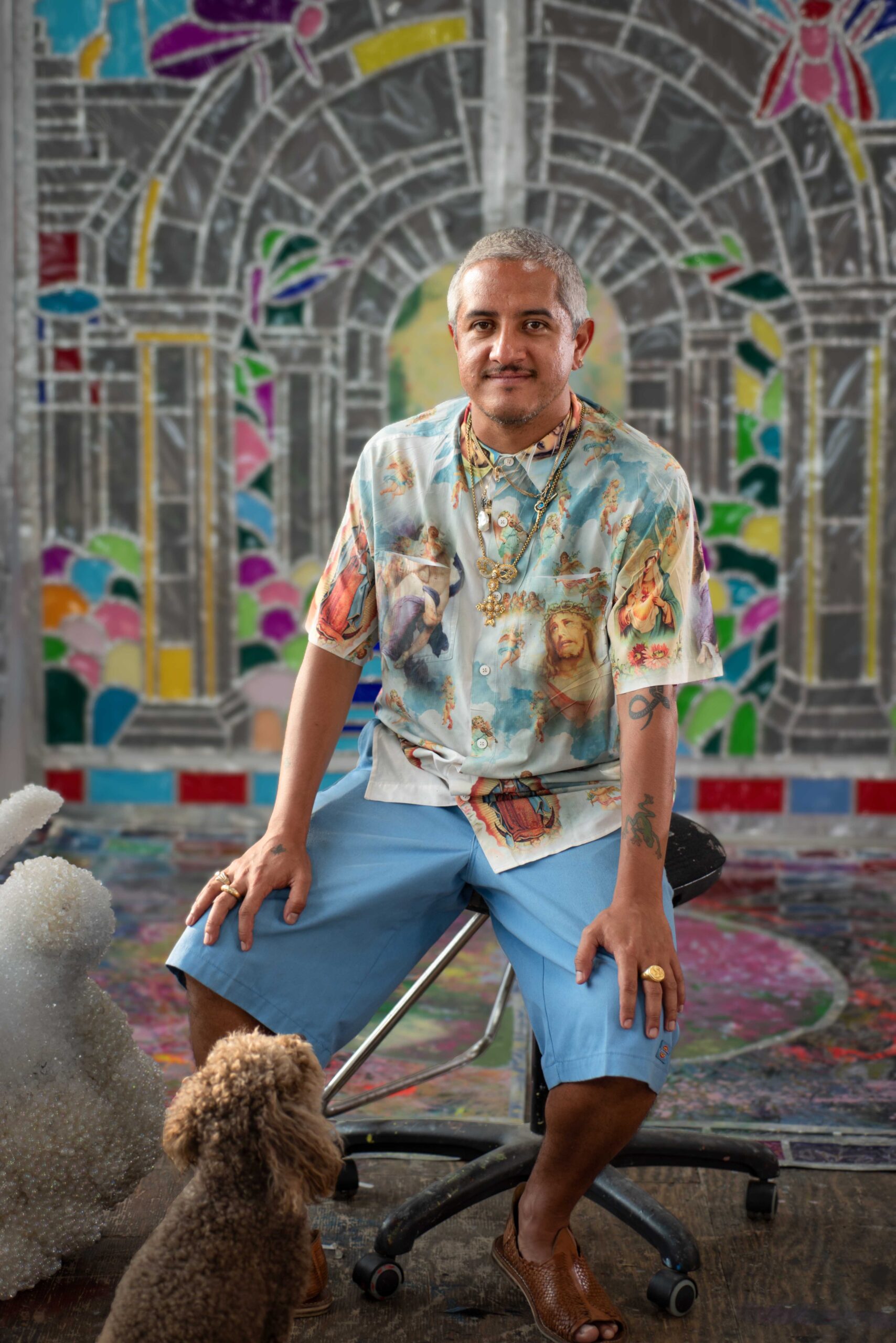

“I’ve seen so much growth,” de Nieves says of his practice of more than two decades. “I’ve also seen so much failure.” The 42-year-old, who arrived in San Diego with his family at the age of 9 and has exhibited at august institutions such as the ICA Boston, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art, is sitting on a threadbare couch on the back of his studio. The floor is covered with stray beads, strips of plastic, and pools of hardened resin—vestiges of the bedazzled, mixed-media sculptures and collages for which he’s become known. His small dog, Penguini (“like little penguin pasta”), is velcroed to the side. “The more I see that I need to work on something, the more it allows me to know myself better,” he says.

De Nieves is speaking ahead of “In Light of Innocence,” his latest institutional show opening Sept. 12 at Pioneer Works in Red Hook. It’s a venue with which the artist has a long history—his band Haribo was amongst the nonprofit’s first musical artist in residence—and one that offers the kind of supple exhibition space suited to his fantastical, more-is-more sculptures. The show has all the makings of a victory lap. Instead, it will come arrive like a valediction.

“This is the last time I want to do this kind of work,” de Nieves says of his signature “stained glass assemblages,” 40 new versions of which will line Pioneer Work’s windows. Made from tape, acetate, and other inexpensive (he hates the word “cheap”) materials, these pieces have been a staple of the artist’s oeuvre since his breakthrough run in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. In past shows, they’ve cast a glittering glow over his sculptures nearby, but for “In Light of Innocence,” they’ll be installed above a gallery inhabited by just one modest, floor-bound work.

This is a restraint not typically associated with de Nieves, a big personality in life and art. But the new stained glass pieces brim with enough symbols and suggestions to offset the emptiness below. Along with the nods to Mexican craft, Catholic iconography, and drag culture that also appear in so much of de Nieves’s art, they feature names, phrases, and images from the Tarot. De Nieves is not much of a practitioner himself, but he appreciates how the cards offers audiences a flexible framework through which to examine their own lives. It’s about “finding these things than can open up a portal,” he says.

That’s what de Nieves is after with “In Light of Innocence.” He sees the show’s negative space as a kind of invitation, a portal through which we might find the guidance we’re seeking. The departure comes with risk, but he’s willing to make that trade. “In a way, this show has really allowed me to think about the next chapter in my life,” he says. Then the artist points to a new stained glass work, embedded with a phrase that has become a mantra as of late: “Growth arrives cloaked in failure’s grace.”

in your life?

in your life?