I composed the interview request carefully, attempting not to fawn, and it was forwarded to her by Lisa Pearson of Siglio, English publisher of the early 1980s photobooks in exquisite editions (The Address Book, The Hotel, Suite Vénitienne, The Sleepers).

I knew from reading other English-language interviews (with Heidi Julavits, Sheila Heti, Brian Dillon, Lucy Ives, and others) that it might be tricky getting Sophie Calle to open up. There would be, I imagined, conditions. I was excited about her ambivalence toward the traditional profile, which I assured her I too shared. What would be the rules of her game? Maybe she’d make me write it as a third-person narrative.

I was ready to be a submissive co-conspirator in her (our) durational project. I also entertained a fantasy that she would ask me to write a novel with her as the main character, and that she would follow those constraints for an entire year, which she asked Paul Auster, Enrique Vila-Matas, Jean Echenoz, and others to do before abandoning the project and cataloging it as part of her “Unfinished” series, displayed at the Musée Picasso in Paris in 2023–24, emptying out her elaborate system of drawers, as well as, in the rest of the space, inventorying and displaying her possessions, while she lived in a hotel for the three months her solo show was on view.

At last, after a short follow-up where I casually dropped that I was the first to interview Annie Ernaux in English after the Nobel, a reply: “Okay! Let’s talk tomorrow or the next day.” This, it turned out, was a preliminary phone call before the formal interview, to clarify the conditions, she said. As I was waiting to pick up my children from their summer camp in a South Brooklyn scrapyard on a boiling hot day, I received an unfamiliar +33 phone call. I clicked the red button automatically, before I realized it was France calling.

She seemed amused then by my awkwardness. She was about to see a play. She told me she wanted to review any quotes and that she would rather I wrote in my voice, not hers, as it wasn’t really her voice being interviewed in another language. I hung up suddenly with a cheerful “Bye Sophie,” but my phone kept on pocket dialing her, in grocery stores, at home. Or she was calling me, these phantom Sophie Calle rings. I never figured it out.

I hung up suddenly with a cheerful “Bye Sophie,” but my phone kept on pocket dialing her, in grocery stores, at home.

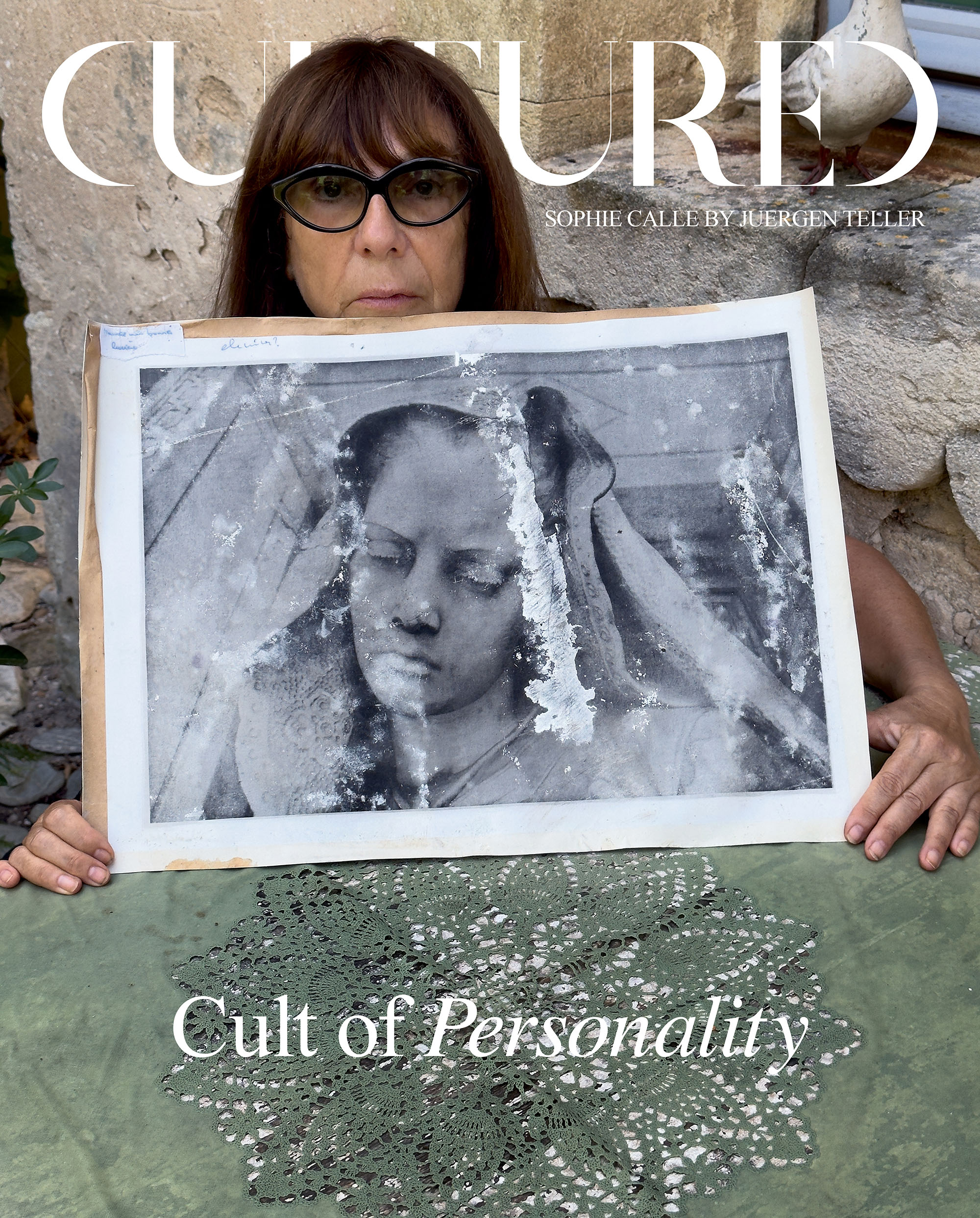

Our real interview began an hour behind schedule. Sophie’s air conditioner was being fixed. I observed her tan arms in a black sleeveless top with those signature glasses and bangs (“Wait, do we need tinted lenses?” a friend asked when I sent him a screenshot). I tried to talk about the heat in Europe, and joked that my building’s super criticized us for having too many air conditioning units. She didn’t seem amused. Maybe it was the language barrier.

In my courtly communication, I wrote that I think of The Address Book as such a distinctly summer project: the discovery of an address book of one Pierre D. on the streets of Paris, and the subsequent interviewing of the acquaintances and familiars within it over the course of a month, amounting to a portrait filled with holes and shadows. This she published daily in a French newspaper in August. Maybe she was able to get away with it because so many were away on holiday. (Isn’t that what art should be—what we can get away with?)

I kept thinking of this summer’s catastrophic floods in the U.S., and a companion book to the Musée Picasso show, a catalog of moldy works after a recent flood in her storage space, work that eerily deals with ephemerality and mortality, including her earlier series of blind people describing beauty, also exhibited at the Picasso show. Also destroyed were the dried flowers, gifts from the architect Frank Gehry, a large photograph of which will be displayed alongside framed photographs of the original flowers at a Perrotin show in New York this fall, alongside a “restaging,” I’m told by a publicist of the Musée Picasso exhibition, which has a retrospective feeling while also playing with the finality of a retrospective.

During our hour-long video conversation, her screen revealed a lofty, light-filled country house, the artwork displayed on the wall chaotic and charming. Was that one of her famous taxidermies hanging behind her at the entrance, or a hunting trophy? She didn’t want to talk about her space, her summer retreat, located in a small village in the South of France, and wasn’t interested, she said, in hunting, which initiated a mildly bickering back and forth when I tried to assert that I was also not interested in hunting.

Was that one of her famous taxidermies hanging behind her at the entrance, or a hunting trophy?

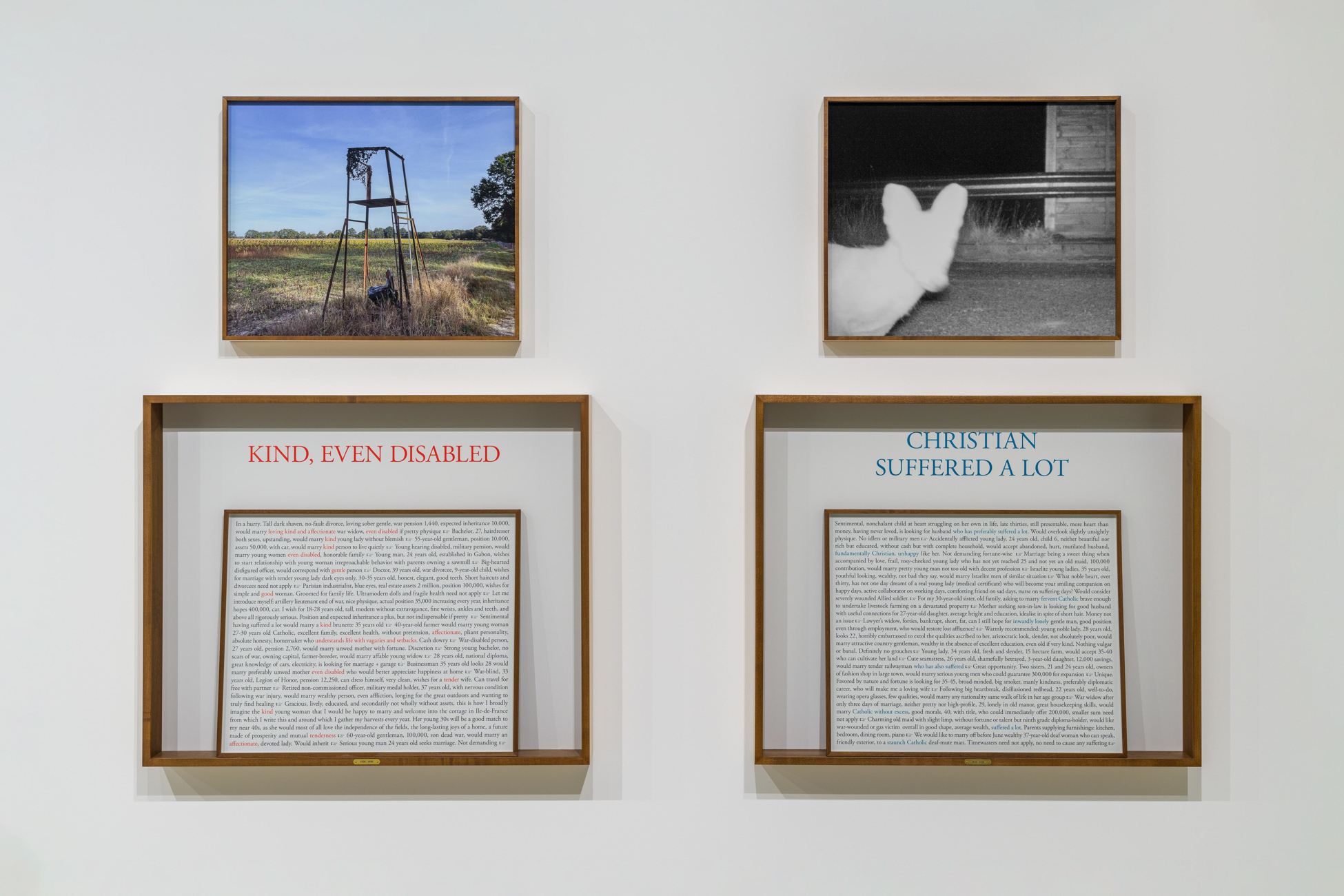

I just wanted to ask about her about her “On the Hunt” series, first conceived at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature (the hunting and nature museum in Paris), where she inventoried the desired qualities from 124 years of lonely hearts ads in a French hunting magazine, displaying them with double-sided nighttime highway surveillance photographs of startled deer et cetera (the prey), juxtaposed with photos of old-fashioned hunting towers taken by Calle in the countryside (the predator).

In 1905–14, men were obsessed with virginity (“with or without stain”), while women of that time pretended to be happy marrying a Howard Marshall II. By the time of the Tinder profile, the main concern is proximity (proximity, incidentally, was often an impetus for her earlier follow pieces, a connection I try to make to Calle, who regards this assertion with her version of a dry, Gen Z stare).

“What was she like???” the (mostly) young literary (mostly) women texted me when they heard about our conversation. “Very French,” I respond. “Not into small talk.” “Is this the interview, this?” Calle said when I began to read from my handwritten questions. “Do I have to answer that?” She was annoyed but direct when I asked questions about the recent work. She wanted to keep to the facts, which was kind of as it should be. Which were we, prey or predator? Interviewer or interviewee?

The hunting series, now on view at Paula Cooper, is a knowing subversion of the Sophie Calle project, especially this earlier stalking period that she is best known for in the U.S.—not only The Address Book, but her project Suite Vénitienne, where she followed a man through Venice and staked out his route, including his hotel. I asked her how she developed her specific writing style, that dry, witty, direct voice, like a detective novel. She was so young when she began these projects. She corrects me—“I was 26, I was not young.”

“I was not sure of myself as a writer or as a photographer. I think it was this insecurity that made me write on my photos … and it’s the fact that people have to read standing that made me find an economic style. I have to find an economic language, going straight to the point … I edit until I cannot take any word out. I start with many details and I cut, cut, cut until I think that if I cut more people won’t get it.”

The wall and the book, they help each other, she says to me. But also, she clarifies, the books allow for other people’s words to be published more completely—like the 107 interpretations of a breakup letter in “Take Care of Yourself,” including those of a tarot reader, a parrot, a psychoanalyst, her mother, a 9-year-old, a Talmudic expert, a crossword puzzle maker, a chess player, an Ikebana master, an accountant, and many scholars, writers, and performers, originally shown at the French Pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale in what may be the most exhaustive response ever to a bad piece of writing.

I realized the Sophie Calle I encountered during our interview was the editor—one of her many roles as an artist, in addition to detective and archivist.

I realized the Sophie Calle I encountered during our interview was the editor—one of her many roles as an artist, in addition to detective and archivist—economical with language in her vignettes and stories, condensing lengthy conversations with others into epigrammatic portraits that are, even in translation, unmistakably her own.

At some point, she reminds me that we only have 20 minutes left and I should ask my questions if I have them. I wanted to talk about the interventions in the “Because,” or “Parce que,” series, both the book—the last she made with her frequent collaborator Xavier Barral before his death—as well as the wall pieces, which are exhibited both on the fourth floor of the Musée Picasso show and now in part at Perrotin. The writing is also list-like, rendered like a series of wry poems. In the book, we read the text first and then must reach inside the envelope of the facing page to examine the photograph.

In the show, the text is embroidered on a curtain, and people have to lift the curtain up to see the image. Sophie points out to me that the Perrotin show is entitled “Behind the Curtain,” and these newer interventions around her recent photos, the frames and positionings, are to playfully ask viewers or readers to read the text, to understand the reasons for the photo, before viewing the photo.

She launches into a familiar complaint, that people often take a photo of an artwork before, or without ever, looking. The funniest moments in the “Parce que” series contain this frisson of annoyance—staged photographs of Sophie fake breastfeeding a baby, or giving birth to her cat. A spirit of revenge against a critic. “Because I found a seven-word definition of me online: ‘Sophie Calle, artist without child by choice.’”

She seems pleased when I tell her how beautiful I find her photographs of the covered Picasso paintings, protected from dust and light during the pandemic, also in the Perrotin show. She writes of this encounter that when she saw these shrouded paintings, “even before I knew it, I had accepted.” As I’ve read her say before, she wants to make clear that her taking over of the museum—moving her private space into his, at his invitation, she says—was a project of love and play, not of Nietzschean ressentiment.

“I found a seven-word definition of me online: ‘Sophie Calle, artist without child by choice.'” —Sophie Calle

Picasso is no Pierre D., the bumbling male dilettante of Paris she circles in The Address Book, but a “genius” she reveres. “I didn’t want people to misunderstand and think that I was getting rid of him for aesthetic or political reasons.” Instead, she is playing with his absence, with Picasso as a ghost, in keeping with the spirit of so many of her projects. “I know there was a show in New York, I heard it was bad,” Sophie then says, slyly. She’s referring to Hannah Gadsby’s panned takeover of the Brooklyn Museum. “Oh, very bad,” I parrot back, even though I didn’t see it. We both laugh.

Purchase your copy of Sophie Calle’s Art + Fashion issue here.

Creative Partner: Doville Drizyte

Layout by Juergen Teller

Postproduction by Louwre Erasmus at Quickfix

in your life?

in your life?