Few worlds are as fickle as fashion. The 21st century has aided and abetted this quicksand-like quality to a dizzying degree. What used to be a microcosm few dared consider themselves fluent in has turned into a sprawling pop-cultural ecosystem where legacy houses balance their past with the imperative to stay relevant yet distinct from fast fashion’s churn. Creative directors, whose roles have become both more high-profile and less secure, are charged with branding an industry grappling with its own identity crisis. The most visible facet of this turbulent period is a recent round of musical chairs undertaken over the past two years. This fall, the dust settles at last, with no less than a dozen designers making their debuts at sartorial heavyweights like Loewe, Chanel, and Bottega Veneta. With the future of each house’s “codes”—the hues, motifs, and insignias that make up a brand’s DNA—at stake, the pressure is on. To parse through the aftermath, CULTURED convened a quintet of voices who’ve seen the industry from every angle.

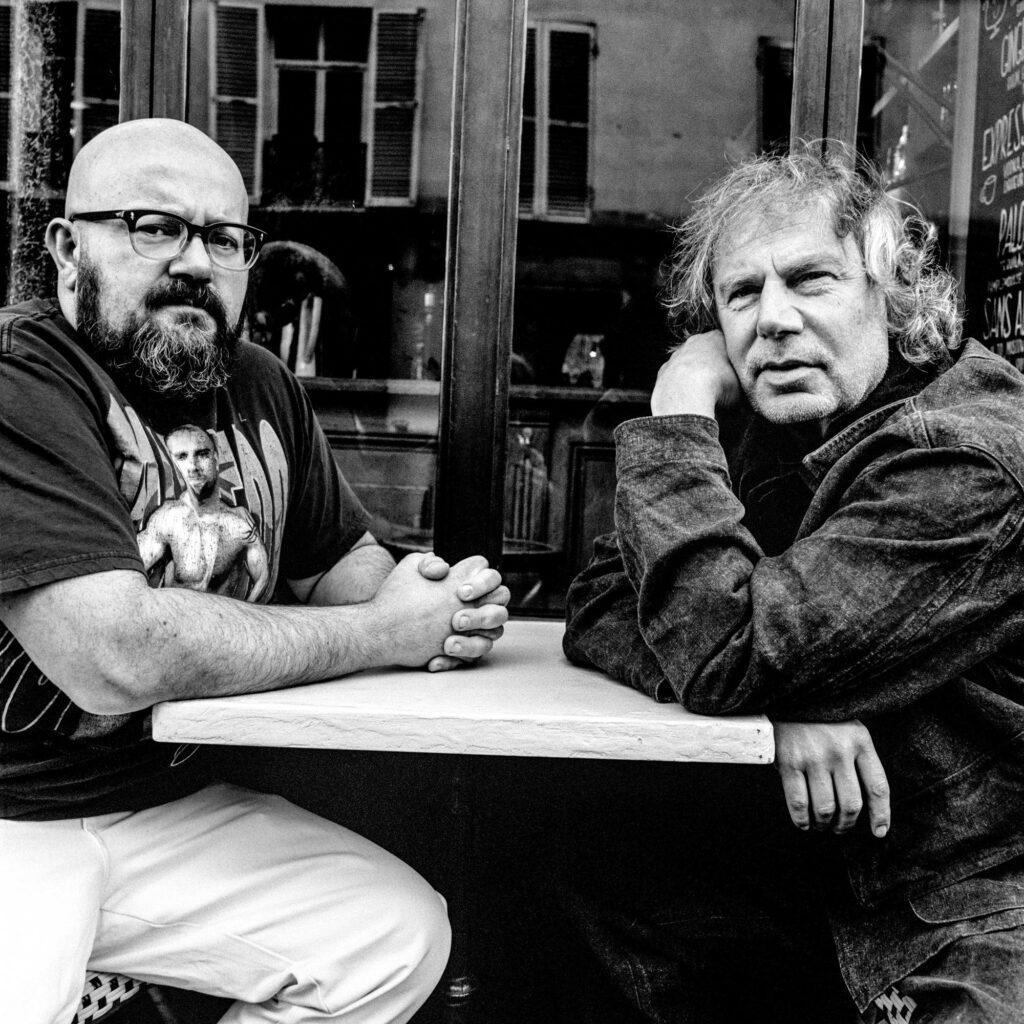

Alastair McKimm, a celebrated stylist and creative director, has worked with brands including Saint Laurent, Calvin Klein, and Versace, and most recently served served as the global editor-in-chief of i-D from 2019–24. Ashley Brokaw, who founded her casting company after working with top industry names including Steven Meisel, helps define the faces of the moment, visualizing Prada and Miu Miu runway and campaign rosters today. Mathias Augustyniak and Michael Amzalag are the co-founders of M/M (Paris), a creative agency renowned for its work in art direction and graphic design, including collaborations with fashion houses such as Balenciaga, Loewe, and Givenchy. As a former fashion editor and director at publications like W, Women’s Wear Daily, and The Wall Street Journal, Meenal Mistry now applies her expertise in content for leading luxury brands, first at Bottega Veneta, and now at Tory Burch.

These insiders stitch together a weary yet hopeful picture of the world they’ve devoted their careers to—and the rollercoaster ride it’s been.

What have been the biggest changes in your line of work since you started?

Ashley Brokaw: Well, we had dial-up Internet! Lots has changed. When I first started, everything was about relationships over the phone. The changes in technology have made things quicker and easier, but also a bit less personal. The real shift has been in the model ecosystem itself. We’ve moved away from the supermodel era, where a Vogue cover was genuinely life-changing. Today’s landscape is more fragmented—we’re seeing fewer traditional models on major covers, and new models face significantly more competition to break through. The path to recognition has become more complex, and honestly, I’m not sure there’s a modern equivalent to what a Vogue cover once represented in terms of career impact.

Alastair McKimm: Pretty much everything has changed, but the biggest change is the pace and consistency. The workflow was very different in the early 2000s. We would see the collections, go back to London, work on ideas, plan the season, shoot stories, and publish, in that order, over months. There were two seasons a year. Now it’s all been melted down into a consistent stream of content creation and a merry-go-round of fashion events.

Meenal Mistry: Fashion has become entertainment and an integral part of pop culture. The industry felt tiny and niche when I started. You got to see a few immediate images from runway shows in WWD or a newspaper. Otherwise, fashion magazines controlled what you saw and dictated trends. Livestreams, vogue.com, and social media broke down that wall. This tectonic shift made everyone a content creator, including brands. That’s why you saw an influx of fashion editors leaving magazines to work for them. Suddenly, it wasn’t enough to shoot a campaign, buy print ads, and rely on magazines to tell your story. You needed an “always-on” storytelling strategy and an in-house team.

Michael Amzalag: When we started, it was not such a big industry. We started with designers that were in charge of their own brands. The idea of a creative director didn’t appear until Tom Ford. It’s at the turn of this century that the Tom Ford and Gucci template established something that has affected the scale of an industry that has grown 10 or 20 times the size of what it was. In the 1990s, Dior and Chanel didn’t represent much for people outside of their clients. They were not even part of the fashion conversation. Everybody was excited about Helmut Lang, or the Japanese, or Jil Sander. Going to see a Chanel show was only valid for a certain type of person.

Which fashion show would you describe as the best you’ve attended? What made it so unforgettable?

Brokaw: The Versace Couture show, January 1999. I was working for Steven Meisel, and we flew over to see the show and shoot the campaign right afterwards. It was in the basement of the Ritz, and the runway was just a floor over the pool. There was a palpable buzz of energy and excitement, and the afterparty was also Kate Moss’s 25th birthday. She came with the hair from the show. The clothes were also incredible—these stingray sculpted dresses that looked sequined in the light. Absolutely one of a kind. I think it was the first time I saw couture clothing up close.

McKimm: I’m not sure about “best,” but the show that affected me the most was very early on in my career: Yohji Yamamoto Spring/Summer 2003, during the Paris shows in 2002. It was the launch of Yohji’s collaboration with Adidas. All these incredible black Yohji silhouettes styled with Adidas sneakers, the models walking in silence. It was the first time I saw a show with no music, and the silence was very powerful. I was so inspired to see the mix of high fashion, sportswear, and street-wear, which was ever-present in the Buffalo movement that I was obsessively studying at the time.

Mistry: Alexander McQueen’s Fall 2006 show, the Widows of Culloden, is possibly the best show I ever attended. The clothes explored the romantic side of his Scottish heritage with fantastical headdresses. It ended with a beautiful, ghostly projection of Kate Moss, especially poignant in the wake of a recent scandal. I was moved to tears; I recall many people wiping their eyes. McQueen’s codes were raw and auto-biographical. When he fully deployed them, you couldn’t help but have an emotional reaction.

The best show I worked on was Tory Burch Spring 2022, my first season at the company. Downtown New York was still recovering from the early days of Covid, and the show celebrated its return to form—staged right on Mercer Street in SoHo with a local street fair on either side of the runway. The collection, a modern homage to Claire McCardell, signaled a new direction for the brand. It was a perfect early fall day, and people were so happy to see each other again.

How do Internet trends influence your approach to your work?

Brokaw: If something is trending, that’s my cue to pivot. If I’m on trend, I’m behind the ball.

Mistry: I always have an ear out for Internet trends that might connect to what we’re messaging at any moment. But the microtrend cycle has become comically accelerated. Something pops up and immediately everyone—influencers, brands, publications—pounces and very quickly you’re sick of it. We started a brand Substack at Tory Burch in 2023, and I find the fashion coverage there to be incredibly interesting. There are certainly trends that bubble up, but I see more depth and breadth in writers’ perspectives. We’ve collaborated with many of them, and it’s a fun platform to hook into.

What are you hoping to see or feel on the ground this season? What do you expect will disappoint you?

McKimm: I don’t expect to be disappointed. With so many visionary creatives of my generation taking the helm of the most prestigious houses, I know it’s going to be an incredibly inspiring season. I expect to see respect for house codes, but with an emphasis on the here and now.

Mistry: I try to never expect disappointment. There is immense expectation around these debuts. My feeling is that everyone needs to slow down a little and give new creative directors a moment to develop their vision. My PSA? Let’s all take a beat before rushing to judgment. It’s important to remember that many of the ones we think of as successes took a few seasons to hit their stride: Riccardo Tisci at Givenchy, Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli at Valentino. It would be a pity if a creative director played it safe because they felt a single collection makes or breaks them.

Brokaw: Honestly, I’m not really paying much attention to this season. I get that this season is big and offers that initial buzz, but a creative director’s true breakthrough—to me, usually—is seen in seasons four and five, where rebranding efforts reach critical mass. That’s when you see if consumers genuinely embrace the new narrative. Successful creative transformations rarely achieve impact through debut presentations alone. Today’s creative directors function as world-builders, constructing comprehensive universes across multiple strategic dimensions—from visual identity to retail environments to cultural positioning. I don’t think that believable brand architecture materializes overnight.

Are there particular house codes that are begging for a refresh or rebrand?

McKimm: Chanel tweed.

Amzalag: A rebrand has become such a trick to reactivate brands, almost as a franchise. We’ve reached a point where everyone’s going back to the original logo after trying to move away from the original logo. At some point, there is a need for stability, for work that has real craft and appeal. When they don’t, or when they are too blunt, it doesn’t work for long—it only has initial shock appeal. We’re now realizing that people want things that are more stable and that they can relate to through time.

Mistry: In a post-Demna and Hedi [Slimane] world, I don’t know that anything is untouchably sacred. Perhaps a better question is whether it’s ever a good idea to change a deeply defining code. Those blue-chip codes—Chanel’s double Cs and tweeds, Bottega Veneta’s intrecciato, Valentino red—are a necessary anchor for future-facing creativity. From a storytelling perspective, house codes supply the weight and romance of luxury and heritage. At Tory Burch, even though the brand has evolved from when it was founded in 2004, the original double T is still essential, and it’s interesting to see how the team pushes it and plays with it every season.

Jonathan Anderson’s first Dior show saw so much support from other creative directors, who all sat front row. Do you see that as a turn toward a warmer, more familial industry atmosphere?

Brokaw: God, I hope so. I really feel for these creative directors. It can be isolating—they so often get pitted against each other in the press. It’s nice that they can celebrate their individual talents, and it’s important that they support each other. It’s tough out there now, and there is so much pressure on these creative directors to deliver in environments that they don’t fully control. They are so front-facing that I feel an extraordinary amount of pressure is heaped on their shoulders.

McKimm: There’s definitely a camaraderie amongst creative directors. In my opinion, it’s due to the disposable nature of an already very challenging job.

Mistry: I’m not sure how much I would read into this. I recall a big designer turnout for Raf Simons’s debut at Dior—Riccardo Tisci, Azzedine Alaïa, Diane von Furstenberg, Marc Jacobs, Olivier Theyskens, Alber Elbaz, and more—which was over a decade ago. This may simply be what happens in Paris when there’s a major debut with a lot of expectation from a designer whom people genuinely like and want to support.

Augustyniak: I’m more drawn towards the interpretation that, even while competition is valuable, showing support is good too.

Of the creative directors who have shuffled their positions recently, who do you think is genuinely well-suited to channel the history and house codes of their new placement?

McKimm: In my opinion, this round of hires makes sense. Jonathan, Matthieu [Blazy], Demna, Duran [Lantink], Glenn [Martens], and the already-proven Michael Rider—these are all modern thinkers who have enough experience to handle pressure and develop their own visions.

Mistry: I’m especially looking forward to seeing what Matthieu does at Chanel. There’s a deep well of references to feed his rich imagination. Jonathan is an inspired choice at Dior. Both are well-suited appointments. The combination of a strong imagination set free in a house with strong codes and source material holds a lot of promise. I also think Sarah Burton is well-poised to sharpen up the vision at Givenchy. I only wish there were more women in the mix. I really enjoyed Michael Rider’s debut at Celine. It wasn’t a wholesale reinvention, but a cocktail of familiarity and newness, with some very fun styling.

Augustyniak: Jonathan managed to get people to start to look at Dior again. Will it be a big success? I can’t see into the future, but at least it brings dialogue—we are discussing it. What’s good about this group is that there are many people in the mix who are obsessed with fashion. Jonathan is obsessed with fashion. Fashion is obsessed with fashion. There is no doubt about this. These are people who are making the fashion world move somehow.

in your life?

in your life?