Since its founding in 1968, the Studio Museum in Harlem has pulled off a balancing act that has eluded many of its peers: simultaneously cultivating an intimate relationship with its neighbors and serving as a beacon for boundary-pushing contemporary art internationally. For the past seven years, however, America’s leading institution dedicated to the work of artists of African descent has been closed to the public while laying the groundwork for a new chapter. On Nov. 15, it will open a seven-floor, 82,000-square-foot building designed by Adjaye Associates and executed by Cooper Robertson,

In the art world, the Studio Museum is best known for cultivating a range of emerging talents—both artistic and curatorial—who go on to seed institutions around the globe. To mark its reopening, CULTURED convened three prominent conceptual artists who had significant early support from the museum: Nikita Gale, Camille Norment, and Sable Elyse Smith.

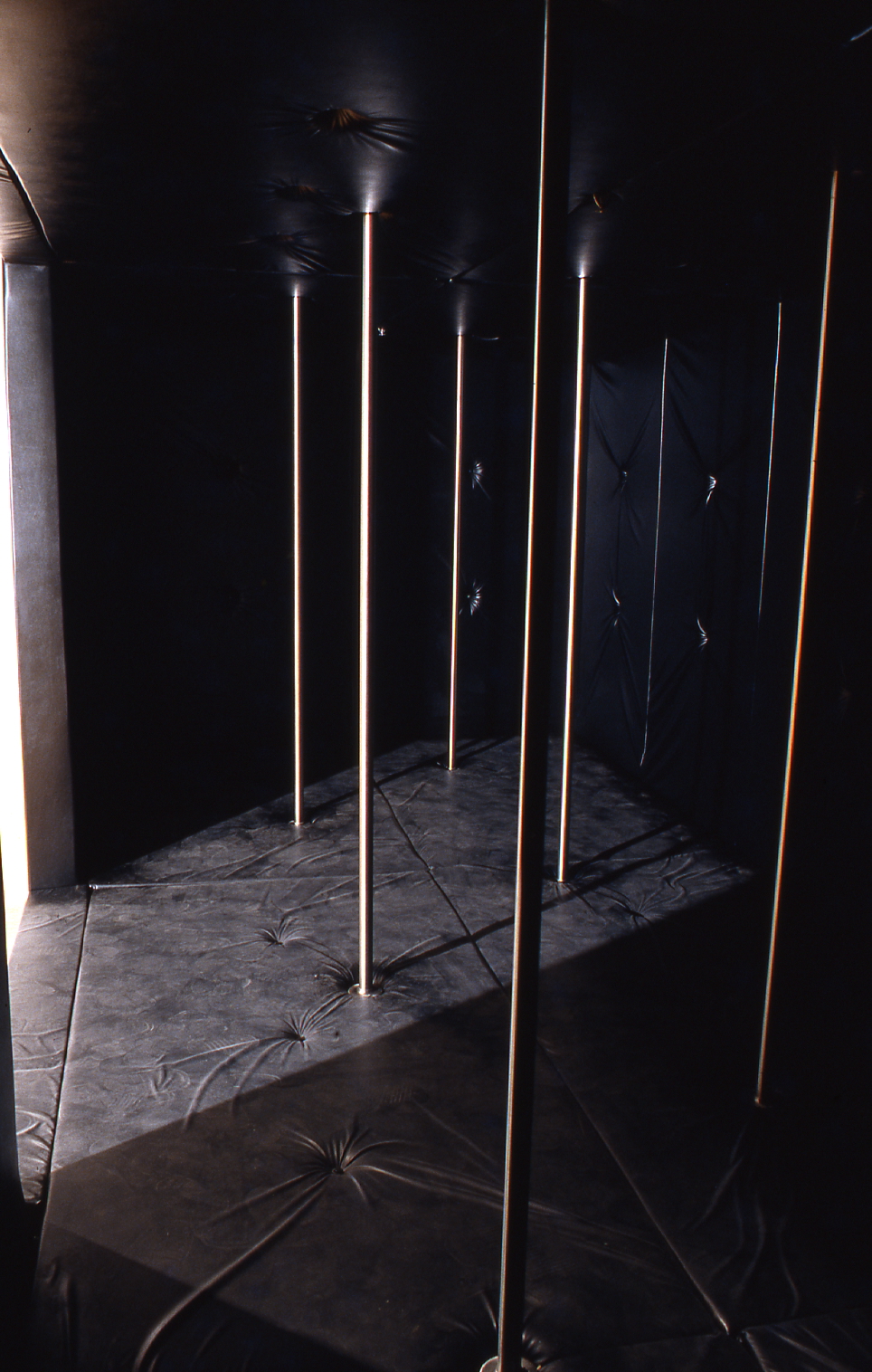

Each was featured in the museum’s distinctive twist on a biennial, a series affectionately referred to as the “F” shows because their titles all begin with the letter. Norment, 55, an Oslo-based multimedia artist and composer, appeared in the first “F” show, “Freestyle,” in 2001 and is creating a new installation made of brass tubing and a chorus of voices for the grand reopening. The LA-based Gale, 41, showed a critical early work—an installation featuring two guitars that made a droning noise—in the exhibition “Fictions” in 2017. And 39-year-old Smith, based in New York and also featured in “Fictions,” was an artist-in-residence in 2018 and worked in the Studio Museum’s education department from 2013 to 2016. Here, they reflect on how the museum has shaped their lives and careers.

CULTURED: What do you remember about your first visit to the Studio Museum?

Nikita Gale: It was around 2005—I was an undergrad and I took this class with [curator and art historian] Kellie Jones. She mentioned that she was on the board of this place called the Studio Museum, which I had never heard of. I ended up going to see the show “Frequency” and it shifted my understanding of what artists do. I was a bedroom musician, taking photos, and kind of dabbling [in art]. To see that there was a space for that kind of creative production marked a profound shift for me. A decade later, I was in the “Fictions” show with Sable.

Sable Elyse Smith: I started to go to the museum after I moved to New York in 2011. When I graduated from my MFA program, I applied for a job in the education department. That was my real introduction.

Camille Norment: Visiting the Studio Museum was a normal part of my routine. I was in the very first “F” show that Thelma [Golden, the Studio Museum’s director and chief curator] organized: “Freestyle.” It was instrumental in affirming my perspective of what I can do, and be, as a Black female creative practitioner. The museum was so kind as to open up a wall underneath the stairway and expose a hidden space in which I installed a sound-based work. The premise of “Freestyle” was so welcoming to me: Black art can be anything that art can be. During opening day, I was standing outside my installation and here comes a man looking at the work and then he looks at me, kind of slyly, and says, “Where’s the Black?” It’s a very important moment because “Freestyle” was acknowledging that freedom. It’s the experience of growing up as a Black female that, by default, becomes embodied in the work. But also, no one should be creatively confined to pre-formed assumptions of what art should be.

CULTURED: Sixteen years later, Nikita and Sable, you were included in the “Fictions” show. What did being part of this series mean to you?

Smith: There [was] a lore around the “F” shows at that point. Ours was teetering on this idea of maybe it’s the last “F” show [because the museum was about to undergo its renovation]. Who knows how that legacy continues?

Gale: Often there is difficulty around legibility as a Black queer artist who is working in sound or process-based works. I recognize it must have been even more difficult 16 years ago. It makes me think about the wariness that I’ve always had around aesthetic categories and genres being so closely linked to identity. I remember my studio visit for the “Fictions” show with [then-Studio Museum curators] Connie Choi and Hallie Ringle. I’d just finished grad school and I was feeling very ungrounded. I was excited they were there, but also in the back of my mind, feeling like, Maybe this isn’t the kind of thing that would fly for a Studio Museum show—that little thought in my head like, Where is the Black? Being in that show opened me up to all of these really fascinating practices. To feel like I’m in conversation with this lineage of artists who’ve made space for a practice like mine to be more understood—it feels very meaningful.

CULTURED: Are there conversations your work can have at the Studio Museum that would be impossible elsewhere?

Gale: Every institution is a reflection of its audience. For me, the difference is that the Studio Museum represents an accumulation of interests around collecting and identity that are very different from most institutions in New York, the U.S., and the world, really.

Smith: With the Studio Museum, I feel like I’m connecting on a level that feels more human, because of their investment and where it is in Harlem, and how that serves as a magnet for people who will approach the work on a slightly different register. Even if I’m having a great conversation about something I’m participating in at MoMA, there is a barrier to intimacy.

Norment: You just look and you know there’s a whole base of knowledge that the work can sit on top of. That’s a shared cultural experience. It’s quite unique and really does change the reading of the works. Anyone who’s encountering the work within this context is actually quite privileged.

CULTURED: Sable, how did your experience in the museum’s education department inform your trajectory?

Smith: I started working at the Studio Museum at the same time I was doing this fellowship in MoMA’s education department, and I had those two things working against each other in really interesting ways. That was a catalyst for me to seek out all kinds of art-related education experiences and turn it into a “career.” [Smith is an associate professor at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.] I felt incredibly alien at MoMA and the complete opposite at the Studio Museum. There was so much space and autonomy. I went to my boss and I was like, “I have this idea for this museum education training program,” and she was like, “Okay, we have this much money in the budget, which won’t change, but let’s try to pilot something.” I started to understand structures in a different way.

CULTURED: What are some of the relationships you formed through the Studio Museum that ended up being formative for you?

Gale: Where do I start with that list? Rodney McMillian, whose work I saw on my first visit, ended up being one of my professors in grad school and a mentor. I didn’t meet [former Studio Museum Associate Curator] Christine Y. Kim during my show, but she became a curator at LACMA and a champion of my work; I would attribute that connection to the Studio Museum. I’m thinking of the museum as a project that is not just about exhibition space, but creating social space, an archive, a collection—all of these important types of work.

Smith: So many curators have come through Studio Museum—Jamillah James now at the MCA Chicago, Naima Keith at LACMA.

Norment: Having known Thelma [Golden] since the early days, it was also her relationship to the creative community that I came into when I came to New York in the early ’90s. [The late critic and musician] Greg Tate was writing about the exhibitions—he became a very important character in my life. It was a lateral structure rather than a vertical structure, which is how I would have described my relationship then to institutions such as MoMA or the Whitney or the Guggenheim—not even vertical, but completely distant, and utterly unrelated to who I am.

CULTURED: You all share a way of working that is interdisciplinary and not easily commodifiable. How does that shape your relationship to institutions in general, but also the Studio Museum in particular?

Smith: The Studio Museum was one of the first institutions that gave my work not just a one-off platform but continuous engagement. Other institutions look at that and think maybe it isn’t such a risk.

Gale: Institutions also have the ability to teach artists how you should expect your work to be treated. The “Fictions” show was the first time I ever had a professional art handler deal with my work. That was a big deal, just watching someone pack the work properly.

Norment: It really has established itself as a space of care—a very overused word, but it’s true.

in your life?

in your life?