Hilma af Klint

Museum of Modern Art | 11 West 53 Street

Through September 27, 2025

Every summer, the flowers take my attention away from the city and my obsession with art—gradually, at first, in my walks through my neighborhood in springtime and, as the seasons progress, in public parks and botanical gardens. Then comes a critical moment, usually deep in August when I escape away into the forest, where I am writing this now. In a remote cabin, not far from Lake Superior, due north from Chicago in the upper peninsula of Michigan, I think through my now annual question: How can the invention of art compete with the wonder of nature? There isn’t a better show on view this summer for thinking through this question—one that is as old as art itself—than the Hilma af Klint exhibition, “What Stands Behind the Flowers,” at the Museum of Modern Art.

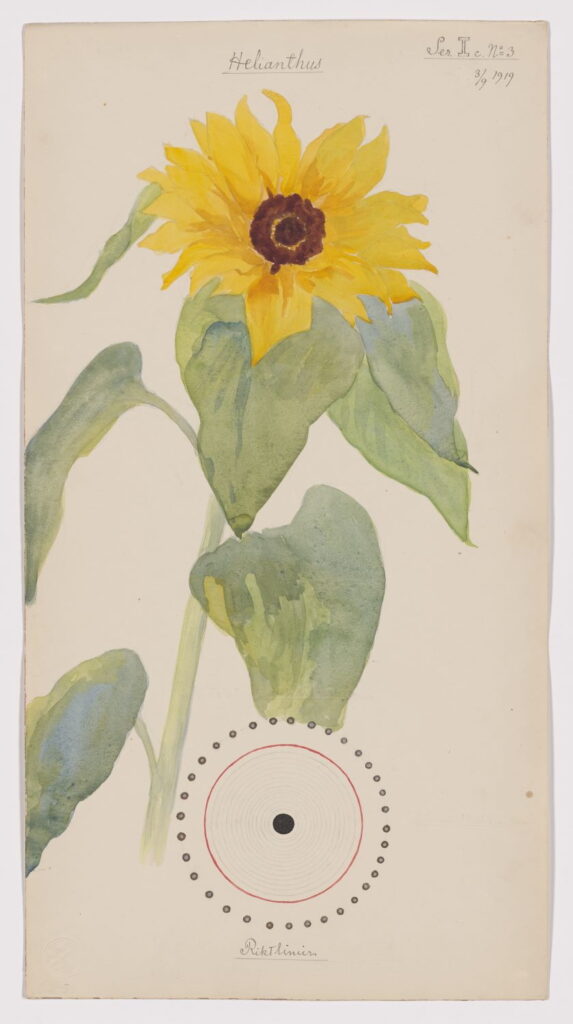

The exhibition centers on af Klint’s “Nature Studies,” a portfolio of 46 works on paper, acquired by the museum in 2022. Completed from 1919 to 1920, when the Swedish artist was in her mid-50s, they feature precise renderings of the anatomies of flowers. Lest you wonder if this is the same af Klint, who is famed as one of the first practitioners of non-objective abstraction (however late she was to receive credit), look more closely: Each illustration includes a drawn diagram that looks like a miniature abstraction. Made more than a decade after her first radical paintings, the selections on view from the series are joined by more than 50 other pieces that help situate the portfolio within her life’s work.

The soft white blob of her Calvatia gigantea (or giant puffball mushroom), made much earlier, in September 1889, rendered in watercolor, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper, seems like a pure, imagined form, reduced to the simplest white biomorphic shape on a black background. And yet it’s perfectly recognizable, on closer inspection. Her Clitocybe nebularis (or clouded funnel mushroom), from the same year, is more immediately identifiable as a fungus. That the title of the exhibition itself can take the form of a question—with the right intonation or added punctuation mark—points to at least two modes of inquiry that animate af Klint’s image-making: one scientific and documentary, the other metaphysical or even spiritual. In the included works, we see af Klint attempting to reproduce the true essence of her botanical subjects, first through careful, earthly observation and then—by pushing further—to reveal their occult secrets. The artist’s deep engagement with the thinking and practices of the spiritualist and Theosophical movements—and her own communication with another realm—guided her restless production.

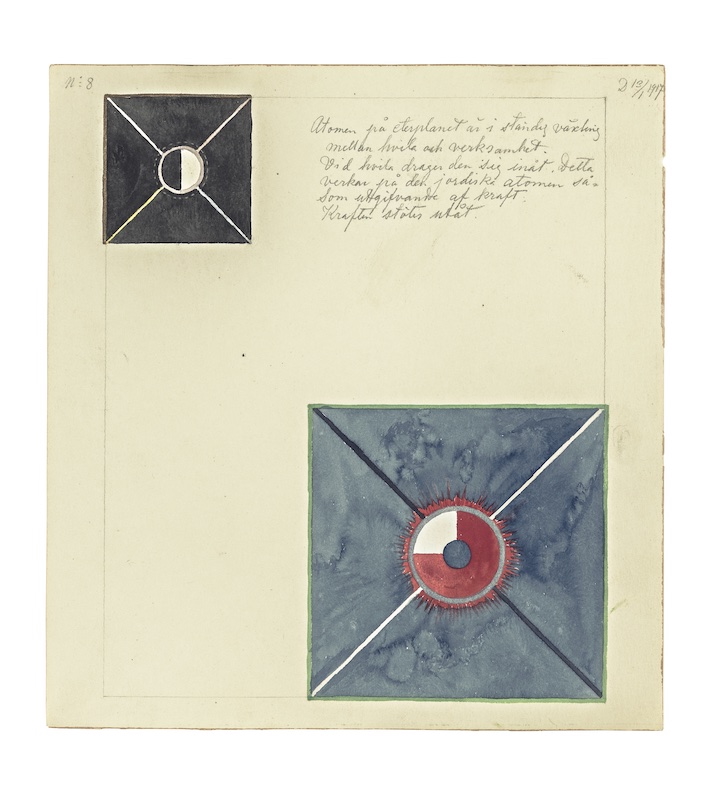

What this exhibition does so well is reveal af Klint’s attention to the essential geometries and colors found in nature. This isn’t limited to flowers. “The Atom Series,” from 1917, provides a fascinating example of the artist synthesizing the latest science regarding the building blocks of matter through her own schematic thinking, exploring it through compositions of watercolor quadrants, X’s, and circles in a variety of combinations, embellishing them with pencil and metallic paint.

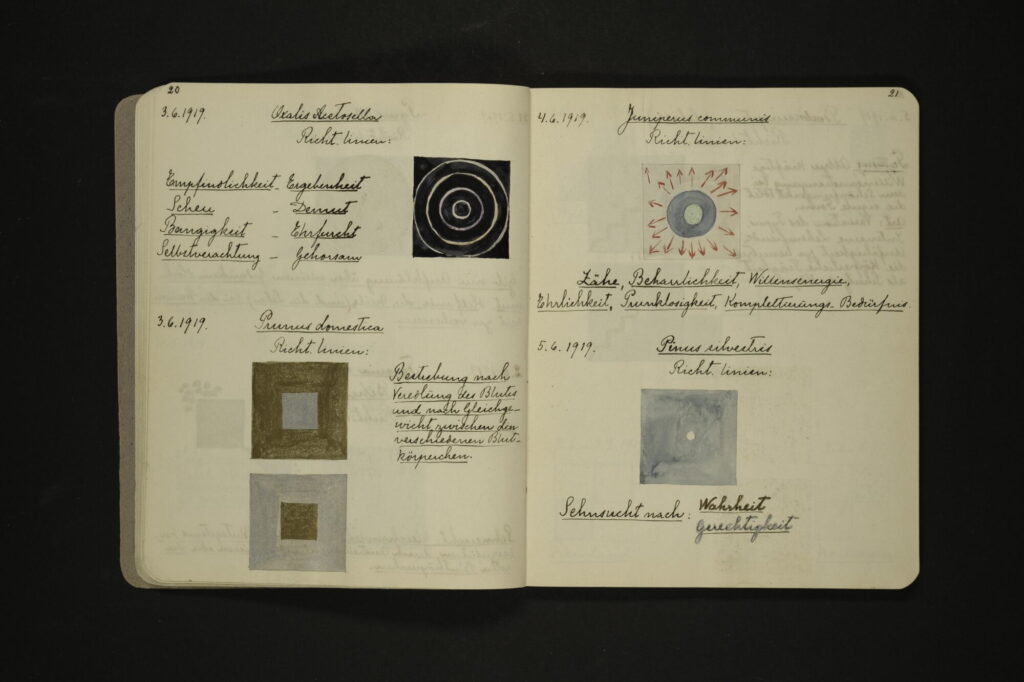

The works seem to relate most directly to the riktlinjer (in English: “directions” or “guidelines”), as she called the more abstract diagrams within her “Nature Studies.” The artist elaborated on and explicated these further in accompanying notebooks. Each flower was not only accompanied by a diagram, it was also assigned qualities that it revealed or represented. The Lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis), for example, corresponds to “Silence, Innocence, Strength;” the common sunflower (Helianthus annuus) conveys “Love is the greatest of all.”

If this leap from observable phenomena to abstract diagramming, and then, to a sort of spiritual pronouncement or moral characterization all seems a little woo-woo (as it initially struck me), I think it is helpful to understand af Klint’s drawing practice as a form of deep contemplation, reflection, or prayer. With their simple geometries and washes of color, these works on paper prefigure, and somewhat resemble, miniature Agnes Martin paintings. And in looking at af Klint’s drawings, and in thinking about them deep in the woods, I recall that Martin frequently found inspiration for her paintings by thinking about trees. Though I see nothing arboreal on Martin’s surfaces, I often find myself thinking about her work during my time in the forest. Af Klint similarly tuned into nature and channeled what she discovered. The MoMA presentation of the artist’s surviving materials charts this sustained project over many years, as it follows the drawings into the more detailed, elucidating notebooks.

Though the show was organized by Jodi Hauptman, it is Christophe Cherix, recently appointed the new Director of MoMA, starting in September, who initiated both the exhibition and acquisition of the portfolio in his role as Chief Curator of Drawings and Prints. I’ll take the show as a good omen. The endeavors of drawings and prints departments often seem minor in the context of museums showcasing large-scale modern and contemporary painting and sculpture, but this show is major. It illustrates how such works on paper can be the site for an artist’s intellectual, formal, and experimental breakthroughs. “What Stands Behind the Flowers” is nothing less than profound.

Out here in the woods, I’m less concerned about the shifting org chart of MoMA, and more attentive to the plants I pass along the two-track path to the main county road. I observe the wild blueberries and raspberries that are now plentiful, and I record to myself the daisies, thistle, goldenrod, and Queen Anne’s lace that also line the path. Af Klint was primarily concerned with the wildflowers that she could observe in her native Sweden, rather than seeking out cultivated ones, and so her “Nature Studies” are much more than an index of individual plants; they reflect a deep engagement with a place. My own stay, in this remote Michigan cabin, is too transitory. I won’t get to know the secrets of the flowers I see each day while I’m here. But I’ve paid enough attention to them, year after year, that I’m not so foolish as to dismiss the idea that they have them.

in your life?

in your life?