Few buildings are immortalized in literature quite like the barn. One beloved contribution to the genre is Charlotte’s Web. In the 1952 children’s book, E.B. White chronicled the unexpected friendship that blossoms between a spider and a pig as the arachnid’s life cycle comes to an end, forever epitomizing the barnyard’s function as a space of nostalgia. Off the page, the barn’s unpretentious aesthetic codes have been consistently co-opted in restaurants, retail spaces, and museums as a shortcut to making people feel at home.

How did we get there? The barn typology as we know it emerged during the Middle Ages, with a central passageway for wagons typically flanked by two aisles of bays. These purpose-built structures evolved to house livestock, farming equipment, and crops. Barns developed to include ingenious features like pitched gable roofs that mitigated snow and rain runoff while creating loft space for additional storage. Others were partially subterranean, allowing storage of potatoes and ice at a consistent temperature year-round.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, English- and Dutch-style barns were farmstead mainstays across the state of New York, from the wooded regions upstate down to the tip of Long Island. Before it was the summer destination it is today, the East End’s thousands of acres of farmland were dedicated to the cultivation of corn, potatoes, and cauliflower. That began to change in 1870, when the Long Island Railroad added a Sag Harbor station, ushering in a new wave of development that would transform the region. Over the last 150 years, farming has maintained a modest foothold in the Hamptons, alongside a burgeoning number of vineyards that have sprung up since the ’70s.

Given this rich agrarian history, it’s no surprise that the Hamptons have adopted the barn silhouette as the mascot of their architectural offerings. In many regional riffs on the humble structure, one recognizes a sense of reverence. The Parrish Art Museum, founded in 1898, was originally located in Southampton in a stately Italian Renaissance Revival–style building designed by Grosvenor Atterbury. In 2005, the institution purchased a 14-acre site in Water Mill, commissioning the Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron to design a structure with a twin-gabled roof, extruding the barn-like facade to a length of 615 feet. The minimalist shed—with its airy ceilings and luminous gallery spaces—acknowledges the Hamptons’s pastoral beginnings as well as the vital role artists have played in shaping the region’s culture. (There’s also a sense of irony in the barn’s architectural legacy out East—last year, The New York Post ran a story with the headline “Historic Bridgehampton potato barn transformed into artists’ sanctuary lists for $4.45M.”)

As the barn typology is adapted to unexpected ends in the Hamptons, one question persists: To paraphrase Gertrude Stein, when is a barn is a barn is a barn? Here, CULTURED’s contributing architecture editor spotlights four local case studies that have withstood the test of time.

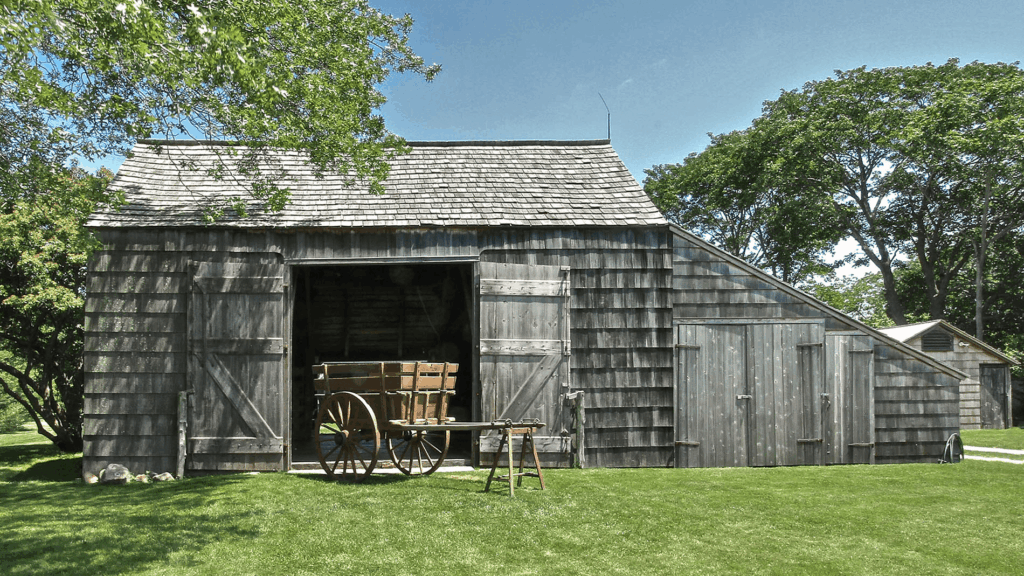

Sayre Barn, Southampton

This colonial barn was built in 1739 and purchased in 1826 by Isaac Sayre, a hotshot whaling captain whose family owned the farm for over a century. Situated at the intersection of ancient trade routes that remained active until the first half of the 1900s, the barn’s exterior was often covered in flyers for traveling circuses, missing criminals, trade store sales, and community events, earning it the nickname Billboard Barn. By the 1930s, ownership transferred to the Dimon family, who added two display windows and converted the barn into an antique store that they dubbed “the most attractive shop on the Atlantic Seaboard.”

In 1954, the family donated the Sayre Barn to the Southampton Historical Museum, located down the road on Meeting House Lane. The barn’s transfer was made possible by laborers who wedged rounded logs underneath the building and literally rolled the structure to its new address, where it took on a new name to reflect its new role: the Old Country Store. In 2008, the deteriorating barn was deemed a hazard and closed to the public. A fundraising campaign ensued, and in 2014, the Sayre Barn was meticulously restored using as many of its original materials as possible. Today, it holds a place of pride among the 14 restored historic buildings owned or leased by the museum.

Mulford Barn, East Hampton

The Mulford Farm remained in the family that gave it its name for 10 generations before finally changing hands in 1949. This 1721 building is a powerful example of an early English-plan barn. In 1990, it was recognized as the second most important 18th-century barn in New York State by the State Department of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

The rectangular form, with its gable roof and lean-to addition, is clad in wooden shingles and was constructed using a typical post-and-beam oak frame with mortise and tenon joints (an ancient interlocking method in which a protrusion from one piece of the wood fits into the socket of another). The Mulford Barn hosted several seasons of performances from the Mulford Repertory Theatre in the early 2010s and is now open to the public as a museum.

Deep Hollow Ranch, Montauk

Established in 1658 and billed as the oldest cattle ranch in the United States—not to mention the birthplace of the American cowboy—Deep Hollow Ranch boasts a series of working barns that support a long-standing tradition of cattle and sheep grazing. The property is surrounded by 3,000 acres of coastal parkland that creates organic boundaries for roaming livestock. Deep Hollow Ranch is open to the public and offers a number of trail rides, including one along the ocean.

The Ranch, Montauk

Across the Montauk Highway is a private property simply dubbed “the Ranch.” Purchased by art dealer Max Levai in 2021, the property features two barns built in the late 1920s by industrialist Carl Fisher, who had grand plans to transform Montauk into the Miami of the North. Ultimately, Fisher’s vision was thwarted when he ran out of money, and the property fell into disrepair.

Levai currently maintains one barn as a stable to breed competitive quarter horses. He refurbished the second barn using only natural materials found on the property, leaving the exterior untouched. Levai has used the 2,500-square-foot galleries to exhibit work by contemporary artists, including Daniel Lind-Ramos, Donna Dennis, and Jamian Juliano-Villani.

in your life?

in your life?