For decades, Glenn Ligon’s work has prodded at the fault lines of identity and how we articulate it. The New York–born and –based artist siphons this inquiry through words, whether pithily arranged in neons, obscured or underlined on canvases, or fleshed out in essays considering his contemporaries or those who came before him. This year, a 52 Walker show paired his work with that of the late composer Julius Eastman, while his most recent solo exhibition saw him take over Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum with a suite of site-specific interventions. A world away from the neoclassical trappings of the latter, Ligon’s next institutional exhibition will open at the Aspen Art Museum this winter. Before then, he’ll stop over in the mountain town for ArtCrush, where he will receive the 2025 Lewis Family Art Award this August, joining the ranks of indelible artists like Nairy Baghramian, Gary Simmons, Mary Weatherford, and more.

Before he takes the stage to accept the honor, CULTURED spoke with Ligon about textual defamiliarization, the evolving relationship between museums and artists, and the state of the American psyche.

CULTURED: Your work has long held a mirror up to America’s psyche. When you look in that mirror today, what’s staring back and how do you plan to communicate that at ArtCrush?

Glenn Ligon: I will be giving a five-minute speech at the gala, which isn’t enough time to unpack the horrors of the American psyche, but in general, I think we are at a critical juncture in American history, where the whip of the state is out and no one can predict whose back it will land on. As artists and as citizens, we must resist the normalization of authoritarian impulses. We must also remember that in the past, it was much, much worse for people of color, women, and LGBTQ+ people in this country, and with protest, struggle, and sacrifice, it got better.

CULTURED: What feelings come up when being recognized by an institution with such an artist-driven origin story?

Ligon: I am always interested in institutions that were started by artists, because that founding DNA still permeates the institution. As long as the Aspen Art Museum is mindful of its roots and prioritizes artists’ wishes, it will continue to be a vibrant, cutting-edge institution.

CULTURED: The Aspen Art Museum is presenting a solo show of your work this winter. Any hints you can drop?

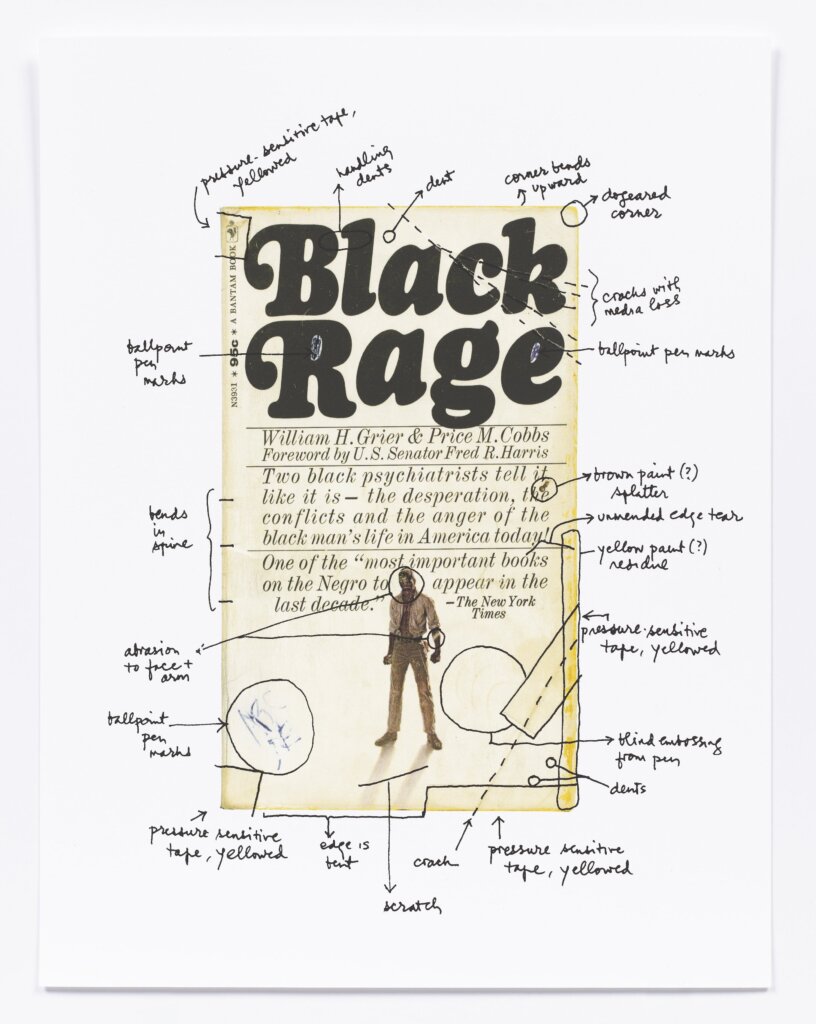

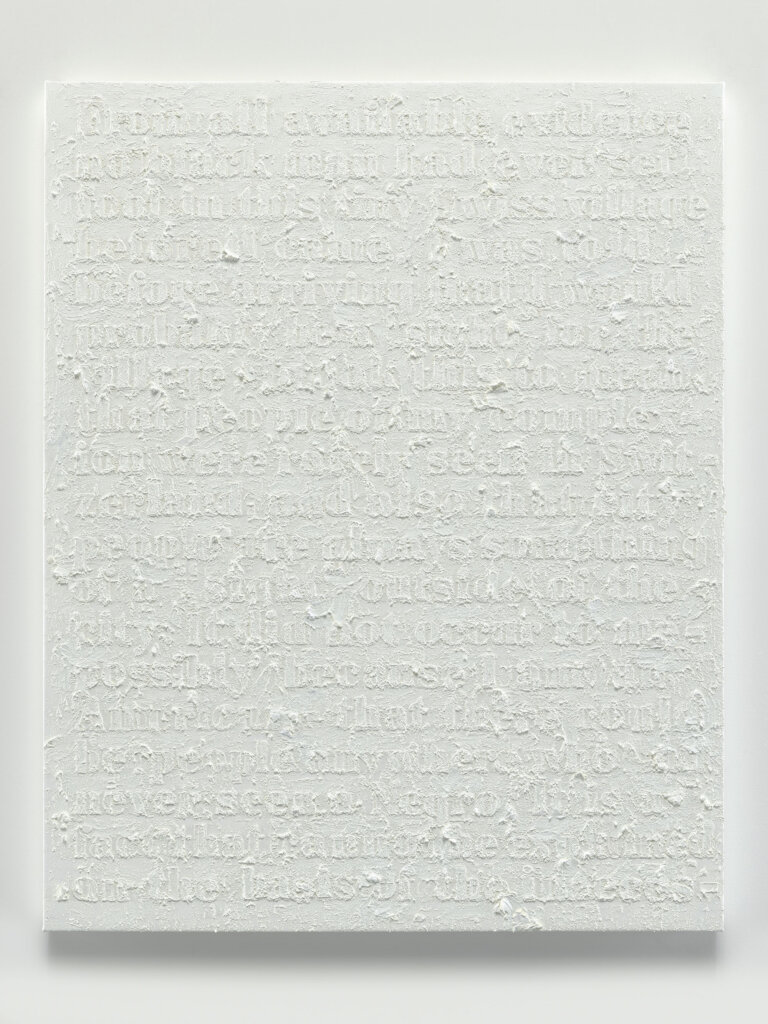

Ligon: The show is focused on self-portraiture, a long-time theme in my practice that has played out in prints, drawings, and paintings. The show also looks at my use of text across bodies of work and strategies of erasure, annotation, and repetition.

CULTURED: What excites you most about working with the museum’s team? Was there a moment or conversation that sealed the collaboration for the upcoming show?

Ligon: There was an early meeting I had with Daniel Merritt, the curator of the show, where we were throwing out ideas about the checklist and possible directions for the exhibition, but we weren’t getting very far. That meeting was on a Friday, and on Monday morning he sent me an email with the outline of a perfect exhibition. He had brainstormed an amazing show on his days off.

CULTURED: Language—fragmented, repeated, erased—has always been central to your practice. What’s a word or phrase you’ve been fixated on lately?

Ligon: I have been fixated on the word “America.” Language, like paint, clay, or any other medium, is there to be played with, and I have done several works which play with the word: inverting it, scrambling it, or rendering it in neon and making it blink off and on in an annoying manner. This is all about defamiliarizing a word that we think we all know the meaning of, but one whose definition we actually don’t agree on.

CULTURED: Artists at this year’s auction can retain a percentage of sales. What does that kind of shift in institutional giving-back mean to you, especially as someone who’s always asked us to rethink systems of value?

Ligon: I appreciated the offer, because I think people forget that artists run small businesses. I am not only supporting myself from the proceeds of my work, but I am also supporting a staff of assistants that help me make that work. Artists can’t always be the ways museums fill budget gaps, so I am thrilled that the museum has acknowledged that there can be more equitable models for fundraising.

in your life?

in your life?