“The culture of the Grateful Dead is a whole other animal,” says David Kordansky, bi-coastal gallerist and lifelong Deadhead. Next week, his Los Angeles gallery will play host to “An American Beauty: Grateful Dead 1965–1995,” an exhibition curated by Dead photographer Jay Blakesberg and his daughter, Ricki, tied to the band’s 60th anniversary. “The magic of what these images possessed was so extraordinary. This is emblematic of so much of what I’ve gleaned and taken from this space, from that community of music lovers, and how it has informed my devotion to artists, creativity, and culture,” he effuses.

The show first came about when Kordansky visited another of the Blakesbergs’ exhibitions timed to Dead & Company’s residency at the Sphere in Las Vegas. He learned that, during the pandemic, Ricki began digging through her father’s archive of nearly 50 years of music photography and started an Instagram account to document the process: Retro Photo Archive. The account took off, growing in 2022 from a social media project to a living archive that contains over 100,000 film photos taken by her father and other pop-culture imagemakers. In Las Vegas, the pair’s presentation of Dead photography enraptured Kordansky, who followed the band on tour “pretty religiously” for three years.

“I thought I had seen every possible image imaginable within that zeitgeist, and it turned out there was a whole plethora of images that I’ve never seen before. It was mind-blowing and they were so beautiful,” Kordansky recalls. A vast collection have been compiled into a book for the gallery, to be published on lead singer Jerry Garcia’s birthday this August, and the accompanying show will feature a selection of the images therein. Works by eight photographers have been blown up to a monumental scale, capturing the similarly sized impact of the band on American culture. “It’s a fucking crazy phenomenon,” Kordansky summarizes.

Ahead of the opening, Jay and Ricki sat down with CULTURED to recount their trip through the archive for a show that would surprise even pop culture’s most dedicated fanbase.

CULTURED: How did you first become familiar with the Grateful Dead?

Jay Blakesberg: My sister took me to my first Grateful Dead concert when I was 15 in 1977, but another guy who was actually in the same grade as my sister, two years older than me, he took me to my first Jerry Garcia Band concert. This guy, his name was Lozzy, and he was your classic New Jersey, 1970s stoner high school dude who would come over to my house and be like, “Listen to this record.” It was the culture of the time. We didn’t have the internet to teach us how to do those things, so we smoked weed, took acid, listened to records on vinyl, and laid around our bedroom, just like in the movies.

Ricki Blakesberg: We’re still doing the same thing.

Jay: Are you still doing that, Ricki?

CULTURED: Ricki, watching your dad work, I imagine it has influenced the way that you approach photography.

Ricki: I’ve been taking photos since I was 12 or 13, probably even younger. I would go with my dad to shows with a little point-and-shoot camera and wander around backstage with him and ask people if I could take some of their pictures. Sometimes they said no, and it was a little scary. When it was 2020 and the pandemic hit, I had lost a bunch of my social media jobs and I had this moment of like, Wow, like I’m living in San Francisco at home with my dad. I can really spend a lot of intimate time with his archive. He has a huge archive of film photos that I felt like weren’t really being seen. To be able to really dig in and see a lot of work that I didn’t even know he had was just so exciting and so beautiful. My dad and I say this to each other all the time, but we, especially now more than ever, live in an era of nostalgia. People that are around our age are bringing back film cameras or trying to find this retro feel. There’s this really beautiful intimacy that you get to experience when you look at archival photography—it transports you.

CULTURED: Going through this archive together and diving in deeper, was there anything that you felt you discovered or were able to see in a new light, even through Ricki’s eyes?

Jay: She’s like, “Wait, you shot NOFX? Wait, you shot Blink-182?” She knew I shot punk rock, but she didn’t know the extent of it. I brought Ricki to see the Flaming Lips at a midnight show practically on a school night when she was 6 or 7 and she was dancing on stage in a giant bear costume with a giant bear head on her head. When they played “Yoshimi,” there’s the part where Wayne [Coyne] karate chops the audience. She just walked out on the front of the stage next to Wayne and did it right next to him. He just looked at her and it was this classic moment, you know?

Ricki: There’s something really special about a father-daughter relationship because we obviously have so much in common, but I have a different eye than him, ultimately. When I’m looking at his archive, I’m seeing things from the perspective of fashion, or things like that, that feel really relevant to today. So something that he might not recognize is really powerful or exciting, I’m like, “No, this is so iconic, we need to get this out here.” There’s this epic shot he has of Björk in this cute little pink dress and she’s sitting down and before that I had never seen that photo, and now it’s one of my favorite photographs he’s ever taken. Being able to have these conversations together and hear his stories, but then also offer my opinions, cultivates a really beautiful curation that you don’t always get.

Jay: Sometimes I get caught up in the technical side of it. Is it a perfect photo? Is it composed? Is it exposed? Ricky doesn’t look at the photograph that way. She looks at it more from an organic standpoint of, is it just a great photo? What story does it tell?

CULTURED: Are there any images that come to mind in this show like that?

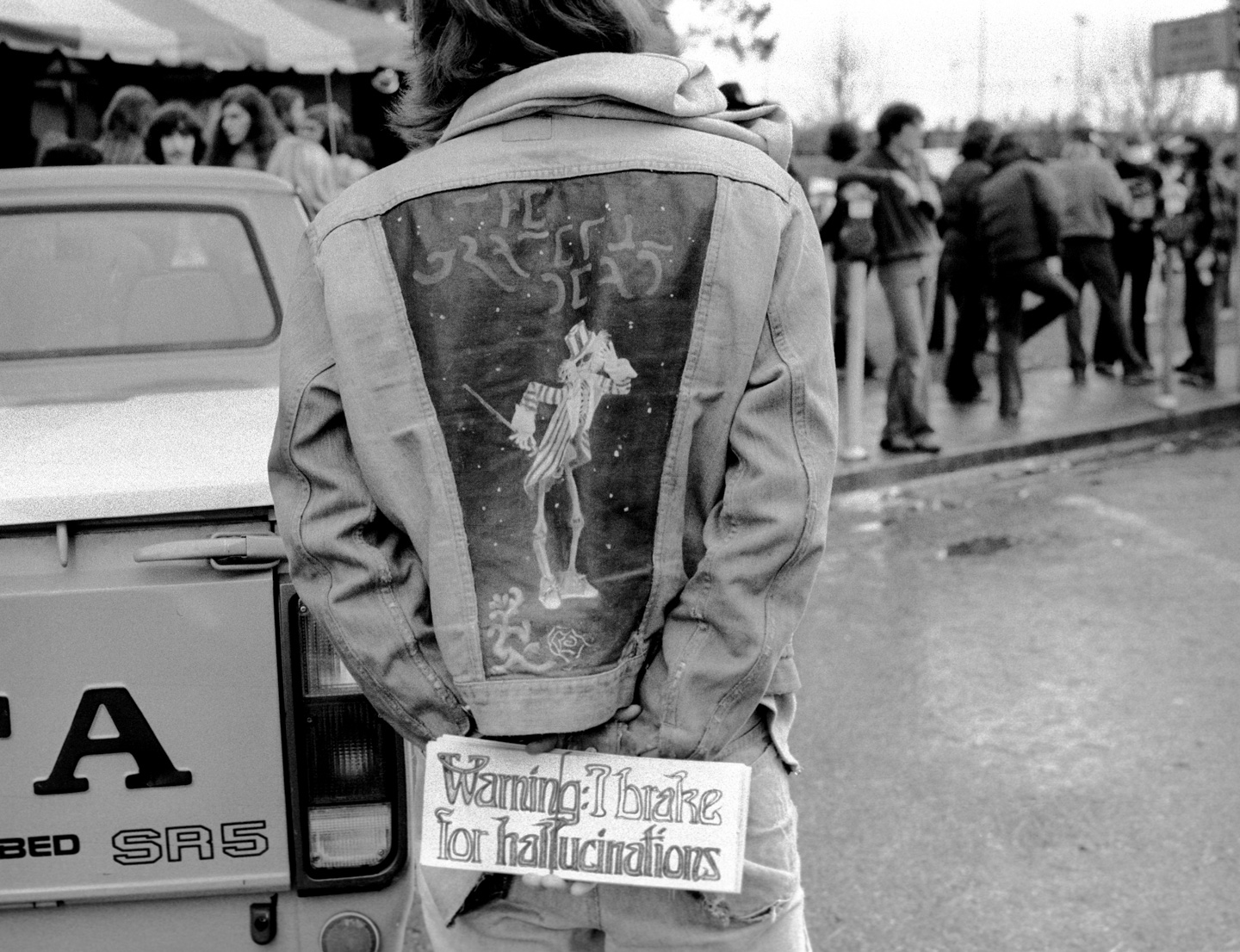

Ricki: Something that’s really important to note about this show is that it’s not just my dad’s photography—it’s a combination of eight photographers. All of these photographers captured the Grateful Dead at a different time, sometimes overlapping. A lot of these photographers are part of our archival collection called Retro Photo Archive that my dad and I own together. When it came to choosing these images, we were trying to be very mindful about picking things that haven’t really been seen by the Grateful Dead world and the Grateful Dead community. They feel like they know everything and they’ve seen everything, and we wanted to keep them on their toes and excite them. Now more than ever, it’s so important to be able to live through photography and live through these experiences. This paints the picture of our society and our world and a lot of things that are honestly happening again.

Jay: I was looking at it from an overall Grateful Dead historical arc, making sure that we really represented some key moments in the ’60s, the ’70s, the ’80s, and the ’90s, and Ricki was looking at it from a visual arc.

Ricki: Obviously this is dedicated to the Grateful Dead, but we also want people who aren’t necessarily deadheads to come in and be able to walk through this exhibit and get an idea of what their story is. They’re such an influential part of our culture in so many ways, and especially now there’s so many younger people who are so in love with what the Grateful Dead represents. We’re taking all of these different parts and it’s really fun to work with someone like David because he’s so smart and he’s such a passionate Deadhead and he has such exquisite taste. He’s so familiar with the art world, so to put these two together feels like an unlikely thing. The Grateful Dead doesn’t necessarily scream fine art in my head. It screams hippies dropping acid, pop culture, and dancing barefoot in the field. So, to bring it into this setting was a really interesting duality. How do we take these images and make them clean-cut but still representative of what they are and who they are?

CULTURED: I love hearing that David Kordansky is a diehard Deadhead.

Jay: I have pictures of him in the Sphere in bliss, eyes closed, arms out, totally dancing. Over the last seven years, when Ricki and I started Retro Photo Archive, we’ve discovered and unearthed an enormous amount of content, both Grateful Dead and non-Grateful Dead. There’s people that shot for two years, five years, seven years, 10 years as a professional photographer, and their stuff was in shoe boxes or banker’s boxes for decades. The book has 275 photos in it, and 150 of them have never been published in books before, which is really not an easy thing to do in the Grateful Dead world. The earliest photos of the Grateful Dead are taken by Herbie Green and we have to have them in the book, cause there’s no other photos of them as the Warlocks in 1965. There was only one professional photographer that went to Egypt with them in 1978, and Retro Photo Archive now owns those photographs. But there’s other ones from Egypt that people haven’t seen as much, and we tried to include some of those. That’s what the book is trying to do: it’s trying to show the history of this band, but also show it in photographs that aren’t so well known.

CULTURED: I would love to talk about this nostalgia moment that you’re mentioning. Concerts are very different now; everyone has their phone, everyone’s taking photos. I’m curious how you think that changes the experience or even the job of a concert photographer.

Ricki: That’s one of the first things that I noticed when I was looking through that differentiated my dad’s photography from a lot of different photographers. He wasn’t just shooting the bands, he was often shooting the fans. None of these kids had phones in their hands. They’re fully present and you can just see them radiating joy and experiencing the moment fully. I’m a huge concertgoer. I love going to live music, and for me, it’s one of the first things that I think about when I’m looking around. Everyone’s carrying a phone. Is everyone really fully surrendering to this flow of the music? The weight of film photography is almost stronger because there was less of it. Everyone can be a photographer now. Anyone can pick up a camera and everyone’s shooting at shows whether it’s on their iPhones or their good cameras. The thing I like about film coming back and people being really excited about using film is it’s creating this moment in time to stop and really be present with the art. For me, being able to look through these archives and see these fans, it brings me so much joy—you can just sense the excitement.

CULTURED: Jay, do you feel like your approach changed over time as you’re picking up different types of cameras, and people are changing the way that they go to concerts?

Jay: Yeah, 100 percent. When I shot film, I shot all sorts of formats. I shot 35 millimeter, medium format, Hasselblad, square. I shot 4-by-5, which is a camera on a tripod with a cloth over your head. I shot panoramic, I shot with plastic toy cameras, which all the kids play with these days. Then of course we had black and white film, color film, fast film, slow film, grainy film, arty film, low light films, etc. So all of those things came into play from a creative palette. Then all of a sudden, we all had the same digital camera with the same sensor, and essentially no software to make things look differently—kind of early Photoshop, which was not user friendly for the average photo person. I had to reinvent myself as a digital photographer in 2008 when I switched full-time. Anybody can take a photo, but you’re trying to be as brilliant as possible every time. My thing was to learn the rules and then break them. For instance my blue period photos are essentially me taking the wrong film that’s balanced for a different type of lighting, shooting it with the wrong light, with the wrong camera, with the lens in the wrong position to come up with something that’s completely different than what everybody else is creating. Those are my blue period photos of the Flaming Lips, Green Day, Joni Mitchell, Tom Waits, and Alanis Morissette, and the list goes on.

CULTURED: If there is something about working with the Grateful Dead, whether it’s the band themselves or photographing the fans who are coming again and again from who knows where, that sets it apart from other musicians?

Jay: As a young teenager seeing the Grateful Dead, and in my 20s, it was a very psychedelic experience. We were taking a lot of LSD. There’s a lot of psychedelic imprinting into your DNA that is unchangeable and you can’t switch that direction. There’s a famous quote somewhere out there, “You can’t quit the mob.” At this point, I’m 63 years old, so I’m 48 years, if my math is correct, into this Grateful Dead adventure. You can’t quit the mob, for one, and the music still turns me on, and the scene still turns me on, and the people still turn me on—capturing all of that. Whether I’m at a Dead show or a Phish show or a Flaming Lips show, or whatever the band might be, I’m still turned on by the art of capturing and documenting that moment.

I was at Goose at Madison Square Garden the other night, and in theory, Goose will be around for decades to come, and there’ll be millions of photographs, millions more that were ever taken of any band on film. But June 28, 2025 at Madison Square Garden will only happen once. Three years out, it becomes a moment. It’s their first headlining gig at Madison Square Garden. Ten years out, when they do 10 nights at Madison Square Garden, it still stands out as a moment. You look at these photos of the Deadheads and at the time, they were pictures of my friends having fun and dancing and driving in cars across the country and having fun. Now you look at them and you’re like, Fuck, there’s no cell phones in these photos. That will never happen again. But we weren’t thinking that at the time. And also we weren’t thinking, Fuck, I’m 20 years old in this photo and now I’m 65. Like, what the fuck happened? That’s what photography has the ability to do, give you those fuck moments but really be meaningful to you.

in your life?

in your life?