“Small Format Painting”

56 Henry | 105 Henry Street

Through Aug. 1, 2025

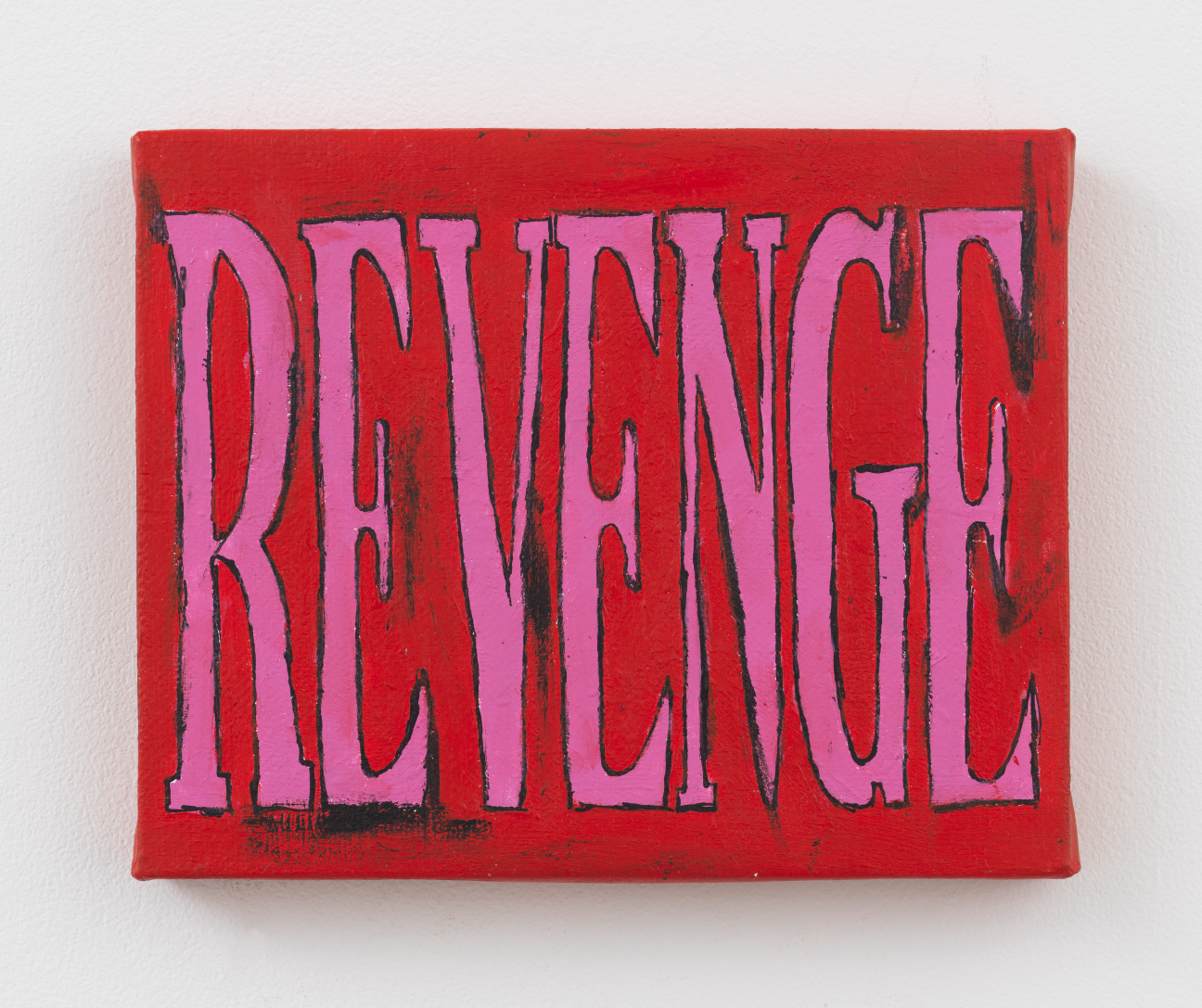

“The group shows are starting,” I texted my co-chief art critic with just a dash of dread. The arrival of these summertime presentations initiates both a seasonal slowdown and a now traditional mix of unfocused, indistinct gallery fare. But “Small Format Painting,” at 56 Henry’s slightly bigger gallery (a few blocks up from its eponymous location), avoids the usual pitfalls with its clever conceit. For this curatorial collaboration between the painter Josh Smith and actor and former gallerist Leo Fitzpatrick, 34 artists were issued a 10 by 8 inch canvas to work with. The eclectic gathering includes both blue-chip artists and skaters-who-paint.

In the corner of the gallery, Larry Gagosian’s face looks out from Nate Lowman’s pointillist constellation of black dots, next to a glittery astral composition that announces itself as a Chris Martin from across the room. (All works are from 2025.) Several contributions may be better described as drawings on linen, such as Rita Ackermann’s great Rider in the Rain, which sketchily inscribes a pair of horses in a turquoise field of wet paint, seemingly with the opposite end of the brush. Farther down on the same wall, Nicole Eisenman uses a similar approach for their four-cell stick-figure comic, What R U Doing This Weekend? And there are plenty of artists here previously unknown to me, or known to me for other reasons, like the skateboarder Mark Gonzales whose Hand Rail Bail is a deadpan crash scene.

I usually try to avoid paying attention to prices, but a peek at the list shows a wild range. A great little painting by Megan Lamb of a glove with her first name on it is available for less than a grand; Eisenman’s contribution is… a lot more. Wade Guyton’s entry—one of my favorites—isn’t for sale, and seems to be simply an inkjet print of a studio reference image for a larger work (one of his iconic X pieces): a cheekily self-aware, flawlessly executed response to the prompt. The concept here brings every contributing artist down to the same size—quite literally. The result is laid back but revelatory, and a lot of fun. I’ve accepted it. Group show season is here, and it doesn’t get much better than this. —John Vincler

Julien Nguyen

Matthew Marks Gallery | 526 West 22nd Street

Through June 28, 2025

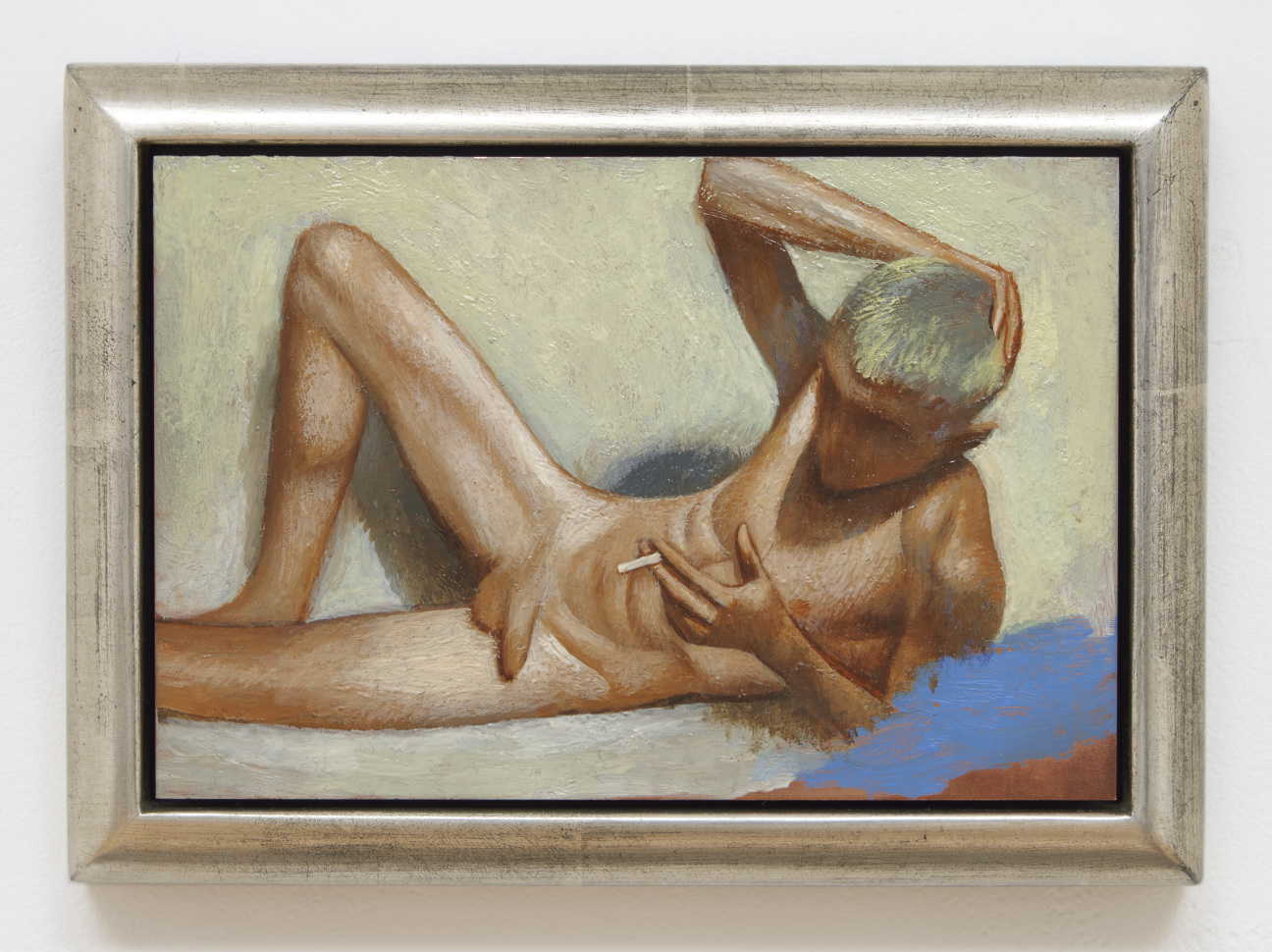

The last time I wrote about Julien Nguyen’s work, I mentioned his silvery palette. It was perhaps for lack of space to explain the appeal of his subdued canvases and fastidious pastels; in truth, many of his scenes have something more like a dryer-lint cast (think wildfire haze; Lucian Freud with less peach and more violet). In the Los Angeles figurative painter’s consummate renderings of both real people (including the occasional self-portrait) and anime or sci-fi-inflected European Medieval and Renaissance iconography, intrigue emerges from the sense that he exercises a degree of self-denial, that everything could easily be more beautiful given his facility with oil paint and oil paint’s capacity for seduction. Or so I felt, looking at his past work. Now, with his new, eponymously titled show at Matthew Marks Gallery, Nguyen seems to skip the medium’s clichés of luminosity to harness the more powerfully lambent properties of copper as a substrate—a technique used by Rembrandt in the glowiest of his small-scale portraits.

Nguyen’s style served as inspiration for Loewe’s Fall/Winter 2023 menswear campaign—the luxury fashion house’s Paris runway show featured images of the artist’s sultry-tubercular muse Nikos blown up into digital scenery. Here, Nikos is tiny. Among the dozen compact oil-on-copper pictures, gleaming frames enhancing their jewellike magnetism, is a snapshot-size nude portrait of him, sprawling and smoking in lemony sunlight. Another, 10-inch-square untitled work captures the model standing before a golden-taupe architectural form, his eyes and mouth unarticulated, as though fused shut. It’s these details—Nguyen’s unsettling treatment of facial features and interior spaces, his inclusion of foreboding nonfigurative foils (like Long Range Strike Bomber, 2024, which depicts a stealth jet soaring above the clouds), and his almost arcane engagement with craft—that distinguish his eccentric art-historical infatuations from more conventional painterly romances with the past. —Johanna Fateman

Kyoko Idetsu

Bridget Donahue | 99 Bowery, 2nd Floor

Through July 12, 2025

In her second solo show at Bridget Donahue, the Tokyo-based artist Kyoko Idetsu paints co-existing records of the intimate and public, folding care work into an atmosphere of collective feeling. Her paintings, in oil on canvas and acrylic on paper, track both strange and domestic fragments: They depict babies crying purple tears, elders, family meals, hospital rooms, children, a washing machine portal, dead bodies. In Only the Dog Knows, 2018, eyes and a black snout are superimposed––and supersized––over a breastfeeding figure lying in bed. In repose, the mother becomes little spoon to a large dog (perhaps the owner of the eyes and snout), who shares real estate on her baby blue pillowcase. It’s tender and spectral. The mother’s visible eye opens just beneath the dog’s giant one. As in Mira Schor’s paralinguistic paintings, the body and text complicate meaning rather than resolve it; Idetsu’s scenes of daily emotional labor establish their own language.

The artist playfully confounds space in her compositions. In Married Couples Boat, 2025, an elderly duo in a hospital room rest like a dropped photograph against a sea of silver glitter. Floating nearby: a giant decaying body and a tiny blue boat. The animating force of the exhibition is this dimensional trespass, in which figures and planes layer and fold into one another, following their own fractured and intimate spatial logic. In a single painting, Idetsu makes the familiar something other with jump cuts from scenes of acute feeling to those of quiet daily life.

The exhibition’s title, “When Words Fail,” suggests a breakdown of language, while the artist’s titles and text accompaniments appear handwritten in silver marker on the gallery wall, in both English and Japanese. Idetsu’s titles, often anecdotal or hyper-specific—as in Man who gets angry when children touch his car, 2025—suggest a semi-verbal world, something overheard or half-remembered. Rather than amp up legibility, the works greet the aporia of the show’s titular phrase, asking: What happens after failure? —Blakey Bessire

in your life?

in your life?