Bodies are everywhere, both in galleries and on their walls, during spring’s transition to summer. But as a subject for the art on view now, the bodily relates more often, it seems, to alienation than to sexiness. In the best work, there’s a corporeal searching—a longing—for connection, an exploration of whether or not it is possible to know another.

To understand the present, we must first understand the past—such logic informs the historicizing impulse behind a show like David Zwirner’s “Circa 1995: New Figuration in New York.” It’s a fascinating mixed bag of works that still feels fresh 30 years on. Well, mostly. A room of paintings by John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage—with the apparent theme of boobs—feels stale and dated as a pairing (hint: it’s Currin’s work that isn’t aging well). More interesting is the conversation between Marlene Dumas with Luc Tuymans in the next gallery. Two lesser Dumas paintings—one of a pregnant woman, the other of two children wading in water—typify her compositional mode, but not her usual power. However, the South African artist’s expressive gifts, such as her paint-into-paint rendering of pairs of held hands, are on full view, in the less typical composition The Visitor, 1995—a scene of five young woman in a dark interior (a nightclub?), turned away from the viewer, looking back through an open door in the distance. In sharp contrast, Tuymans’s Jesus (Christ, 1998) looks like a U.S. federal law enforcement agent trying to blend in while boarding a flight. And why not?

The best Tuymans work here isn’t of a figure; it’s of a flower, Orchid, 1998. In fact, the best paintings in the show aren’t of figures at all. Untitled, 1997, by Laura Owens, depicts a museum or gallery interior, and Peter Doig’s Briey (Concrete Cabin), 1994-96, is a view of a Modernist building through a stand of trees. His transcendent Jetty, 1994, does feature a figure—if only a tiny one—at the center of the picture’s sprawling landscape, an update of Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea, 1808-10, recently shown at the Met. The real organizing theme of the show seems to be: big names, circa 1995, that still command steep prices.

Rooms full of Warholian watersports at Skarstedt, also in Chelsea, tell another history of painting and the body in “Andy Warhol: Oxidation Paintings.” Metallic compounds in the paint chemically react to urine, and the results are the Pop artist’s deadpan response to the gesticulations of AbEx paint-throwing (like those seen in the de Kooning show at Gagosian a block away). I will always associate these abstract statements by Warhol with David Bowie as the artist in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 film, Basquiat:

Basquiat: Oh piss painting!

Warhol: Not piss painting, Jean, oxidation art.

Basquiat: Yeah, I hate cleaning brushes too.

Seen together, the more than one dozen paintings have real heft. They’re much more than a gag—coppery, tonal, evocative (of their own cool, unflinching conceptual follow-through).

Again in Chelsea, Rachel Harrison’s “The Friedmann Equations” at Greene Naftali engages the viewer in spectatorship and the somatic. There are figures here in the form of drawings, mostly busts drawn in colored pencil, but the photos and sculptures interest me most. For the series including Rroe Deloy, 2025, Harrison photographed framed typographical works to play on the name Rrose Sélavy, Marcel Duchamp’s cross-dressing alter ego. Harrison’s images capture a shadowy figure, presumably the artist caught taking the very picture we’re viewing, as reflected in the glass, with the resulting photo then similarly framed. The viewer will likewise catch their reflection, and the resulting mise en abyme brings the viewer’s attention to the presence of their own body in the room, to their own figure in the artwork.

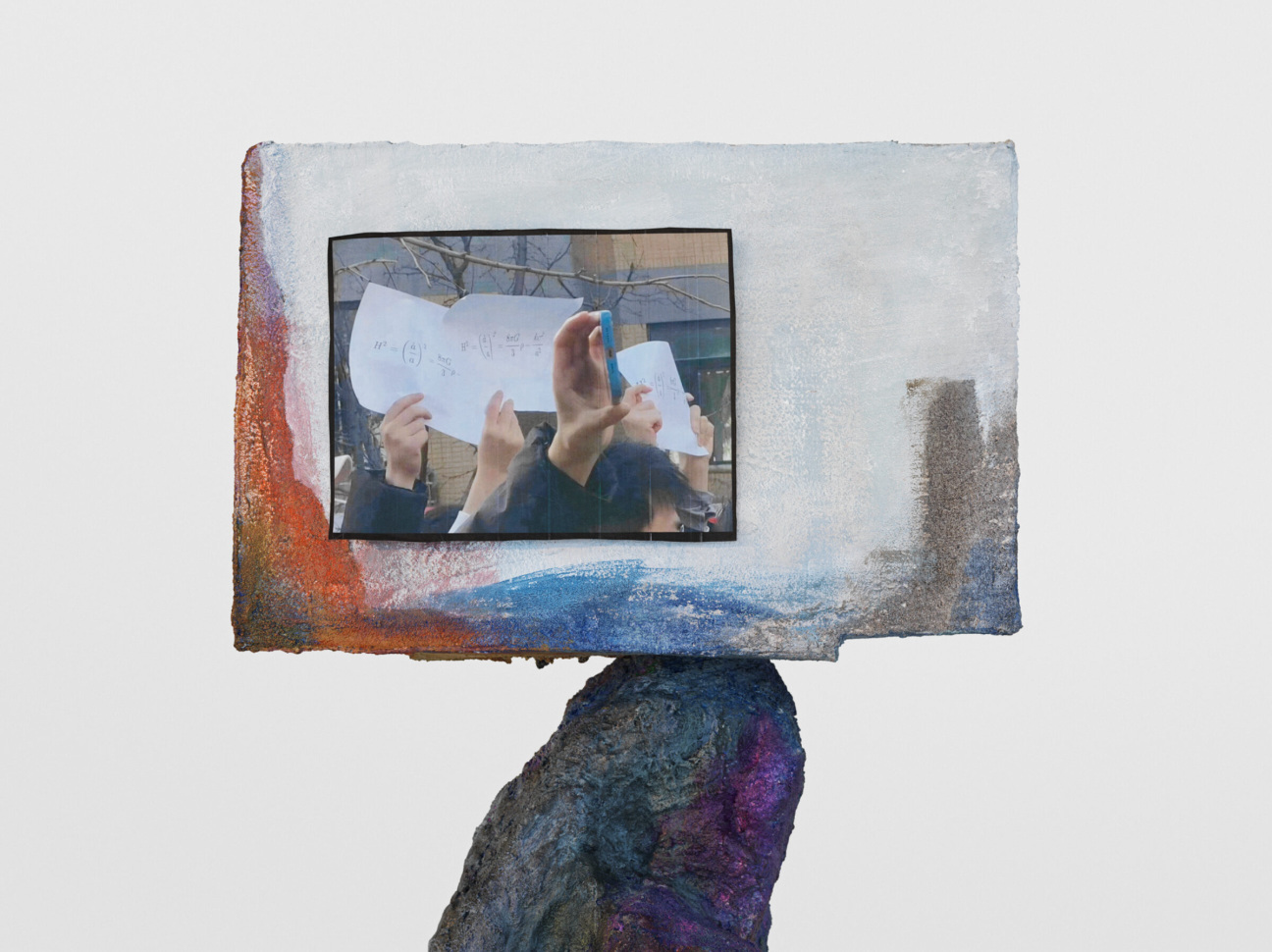

Nearby this series, Harrison’s tall, free-standing sculpture Black Box, 2025, incorporates an appropriated photograph taken at a 2022 student protest in China during the Covid lockdowns. It shows a set of raised hands (and is mounted high, at raised-hand height). Some students hold up mathematical equations while one hand grasps a cell phone, presumably recording or livestreaming the action. The exhibit’s titular equation was named after the physicist Alexander Friedmann’s work explaining the expansion of the universe, which was used by the student protestors as code for an expanded, “open” China, to evade the censors. As with Warhol in his “Oxidation” series, Harrison is interested in what bodies do. Her multifaceted consideration of this theme makes for one of the season’s best shows.

Expanded space also perhaps describes the way one promising show comes up short. What should have been a strong, concentrated show of mostly large-scale drawings by Toyin Ojih Odutola, in “Ilé Oriaku” at Jack Shainman’s Tribeca outpost, instead feels stretched to fill the spacious venue. There is enough good work for a big show, but not one this big. Ojih Odutola’s Showa Era Drag, 2023, exemplifies many of the Nigerian artist’s exceptional strengths in its expressive play of light on volumes (especially drapery); in the way she draws footwear (trust me); and how she creates theatrical spaces for her figures (much like Francis Bacon did with his dramatic staging). But Showa Era Drag looks to have been damaged down its center, with prominent drip patterns and splashing on its surface—an effect that muddles the composition, intentional or not (and I think not). Ojih Odutola’s Always in a Hurry, 2023, shows the artist’s usual facility with depicting transparency falter. When a translucent cloth rests, like a partial veil over her subject’s face, the passage slips into confusion. The potentially wondrous transforms into the academic. The unforced errors of the show are curatorial ones: the gallery’s quantity over quality approach serves neither the artist nor the audience. The relatively new space is made to feel much too big.

Uptown, Anne Collier’s show “Portraits” at Anton Kern proves that excellence doesn’t require large spaces or monumental works. In the artist’s small-scale and great “aura” Polaroids, you sometimes have to search for the subject as though through a mist. The spectral plasma clouds of color provide a painterly overlay for otherwise straightforward portraiture. It’s as if the photos want to capture an essence, not simply a resemblance. Also here are Collier’s better-known large-scale works that show photographic close-ups of eyes resting in developer trays. The tray’s lip for pouring out the chemicals visually echoes a tear duct.

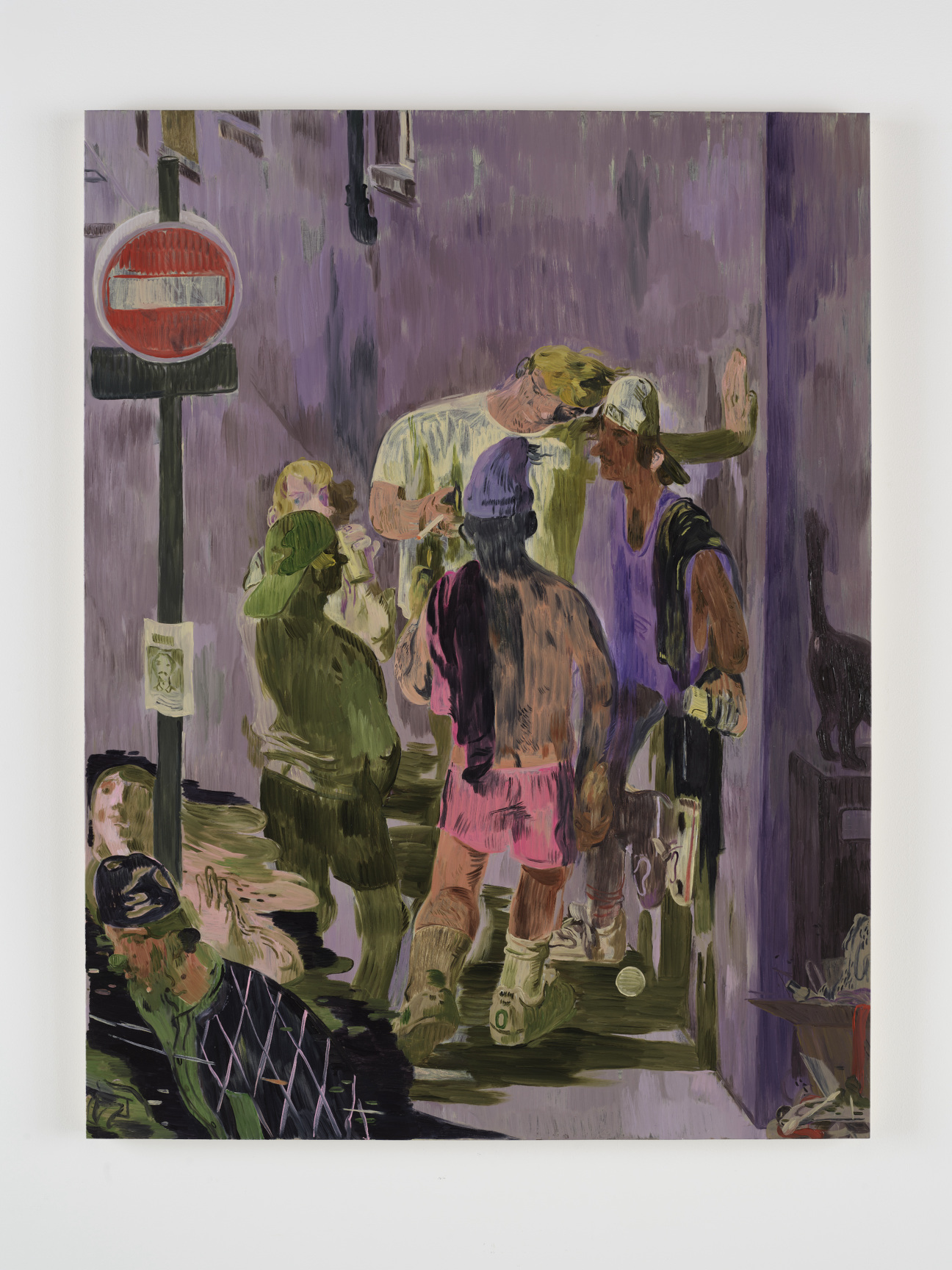

Of all the bodies in galleries now, none are as affecting as Salman Toor’s in “Wish Maker,” his pair of shows at Luhring Augustine in Tribeca (drawings) and Chelsea (paintings). Toor’s characters are alone or together, connecting or longing for connection. They’re in public parks, sitting vigil in hospital rooms, getting intimate in bedrooms, getting to know each other at a house party, or they are onanistically solitary. Toor toggles always between the warmth of everyday life and the heat of desire, between the careful and the candid, allowing space for an accompanying melancholy too. No one is painting figures better right now, by which I mean no one is imbuing painted figures with such humanity.

Like Nicole Eisenman’s, Toor’s figures swerve away from realism at the last moment, with just a dash of a cartoonish quality, especially apparent in his clownish noses. The paintings in Chelsea share the quality of the sketch found in the drawings in Tribeca. Neither show upstages the other. Toor paints a world into being and knows preternaturally when to stop. Nothing is overworked, and many paintings are left as if on the cusp of ripening.

While Toor still paints scenes in his by now signature, moody Toulouse-Lautrecian absinthe green, there are many canvases here that shift in chromatic register across coral, purple, blue, and the wheatfield yellow of the (rare for Toor) unpeopled interior of Mommy’s Room, 2024. In this composition, the body is unseen yet made present in innumerable details (a makeup table, articles of clothing, the lumpy empty embrace of the furniture), as if a mother’s physical presence remains somehow haunting the space.

The glowing screen of a phone often features in Toor’s paintings. It’s a portal of longing for contact with another, a peepshow window, a way of folding away from the crowd or space that an individual is in and shutting out the world before them. But to look at art, out in the world, is to have a body, and to look for windows or mirrors that may help us puzzle through what exactly that means.

in your life?

in your life?